The most fascinating fictional killers

Where would crime fiction be without all the murders, eh? Those dead bodies turning up don’t just give our rugged detective heroes a reason to get out of bed, they also serve as a catalyst, in one way or another, for a destructive journey to hell for those most alluring of fictional characters – the killers themselves.

Where would crime fiction be without all the murders, eh? Those dead bodies turning up don’t just give our rugged detective heroes a reason to get out of bed, they also serve as a catalyst, in one way or another, for a destructive journey to hell for those most alluring of fictional characters – the killers themselves.

Whether it’s shrewd spies, hardened PIs, cocky mobsters, vile serial killers, ice-cool marksmen, good guys caught in the wrong place at the wrong time or outright psychos, captivating killers keep us turning the page.

So here’s a quick rundown of my most fascinating fictional killers – taken from an assortment of works from classic crime novels and gritty noir cynicism to an eclectic range of modern thrillers.

Hannibal Lecter

Okay then, let’s start off with a biggie. Thomas Harris went long and deep to create a truly three-dimensional character here, with Lecter’s backstory, charisma, intelligence, passion and repulsive scope of evil feeling utterly convincing every time you read any of the four novels he features in. The various screen portrayals of the main man, from the chilling Anthony Hopkins to the enthralling Mads Mikkelsen, have only added to the legend.

Michael Forsythe

One of the greats of modern noir, Forsythe is the hero – or anti-hero – of Adrian McKinty’s trilogy of books Dead I Well May Be, The Dead Yard and The Bloomsday Dead. We first meet him as a young illegal immigrant working for a New York crime boss, having fled the Troubles in his native Belfast. But through a series of ruthless double-crosses, global-wide revenge missions and cruel heartbreaks, Forsythe grows up fast. His cunning, coolness and bravery (not many can survive having a foot amputated in a Mexican jungle), not to mention his razor-sharp survival instincts, make him one of the most fascinating protagonists ever created.

Patrick Bateman

Horrifying, shocking… and ultimately transfixing, in American Psycho Bret Easton Ellis introduced us to one of the most brutal and bizarre serial killers of all time – as well as providing an effective social commentary on life amongst New York’s wealthy executive elite in the 1980s. Bateman is one sick, frenzied dude – a sadistic monster in a designer suit in fact – and it all makes for gripping reading.

Jack Carter

Immortalised by Michael Caine in the film Get Carter, Jack Carter was the creation of Lincolnshire author Ted Lewis, first appearing in the 1970 British noir novel Jack’s Return Home and later featuring in two prequel novels. Carter leaps out of these stark books that wonderfully depict criminal life and attitudes to respectability within a hardened sub-section of society in the north of England. An uncompromising mob enforcer seeking revenge for his brother’s murder, Carter’s style is swift and merciless – and we’re with him every step of the way. They don’t make ‘em like that anymore.

Lou Ford

Jim Thompson’s 1952 novel The Killer Inside Me is still talked about today as one of the finest literary examples of a warped mind constructed in the first person. Lou Ford, a 29-year-old deputy sheriff in a small Texas town, does an impeccable job of presenting himself as a regular, unremarkable cop to the locals. Impeccable because beneath that façade he’s an absolute nutcase – a depraved sociopath with sadistic sexual leanings who can’t stop killing people in order to cover his tracks.

The Jackal

One of the most skilled snipers in fiction, the unnamed English professional assassin codenamed ‘The Jackal’ – hired by French right-wing militant group OAS to kill Charles de Gaulle – was the most riveting component of Frederick Forsyth’s 1971 novel The Day of the Jackal. Skilfully woven by Forsyth, who keeps the assassin’s background intriguingly sketchy, the Jackal is patient, methodical, multi-lingual, not to mention tough, as effective with his bare hands as he is with a rifle. His character is explored with perfect brevity by an author who executes the ‘show don’t tell’ technique with aplomb.

Michael Corleone

One of the most iconic villains in the history of fiction, Corleone grows from a youngster with an honest American dream to the head of his family’s mafia empire in Mario Puzo’s 1969 classic The Godfather. He later plays a secondary role in The Sicilian, while Al Pacino obviously took the character to legendary status in the movie trilogy. One of the most compelling factors about Corleone is that he never wanted to be a mob boss in the first place, wanting to lead a simple life with his girlfriend, Kay, but destiny took him to the big gig and in turn gave him a tragic hero appeal.

Martin Michael Plunkett

The frightening first-person protagonist of James Ellroy’s introspective thriller Killer on the Road (initially published in America as Silent Terror in 1986), Plunkett is a child genius who comes from a broken home and graduates from disturbing fantasist to peeping Tom to fetish burglar to schizophrenic serial killer over the course of several years. Many elements of his young adult life, especially the peeping Tom sections, are based on Ellroy’s own criminal experiences, and the unnerving intimacy of the writing results in a powerful read.

Jack Taylor

The brooding, tragic, indignant, sporadically violent but ultimately tender-hearted recurring lead character of Irish author Ken Bruen’s fine hard-boiled series, Jack Taylor is a private eye who sticks up for society’s lost and beaten souls, solving mysteries with a burning sense of justice and a deft splash of human intuition.

Serge Storms

We sign off with a serial killer of a different kind – Serge Storms, the star of Tim Dorsey’s wacky satirical thrillers set in Florida. Inspired by fellow Florida-based comic writer Carl Hiaasen, Dorsey launched his Serge Storms series in 1999 and if you haven’t already it’s well worth joining the ride. Serge, who has been diagnosed with several mental illnesses, bursts into a fit of rage whenever he sees people abuse what he is intensely passionate about – namely the environmental backdrop of his beloved Florida – and promptly dispatches his scrupulous sense of justice. An impulsive vigilante, he commits several creative and intricate murders, many of his victims being disrespectful lowlife criminals, making him one of the most flawed but magnetic murderous character around.

Think I’ve missed anyone? Let me know at @PaulJGadsby

“An atmospheric depiction of 1960s London” – Chasing the Game review

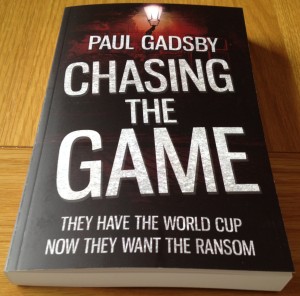

Chasing the Game has been praised for generating “an atmospheric depiction of London in the 1960s” in its latest review.

Chasing the Game has been praised for generating “an atmospheric depiction of London in the 1960s” in its latest review.

My debut crime thriller, a fictional account of the real-life theft of the Jules Rimet Trophy from Westminster Central Hall in 1966, was reviewed by footballbookreviews.com, a website that delivers passionate coverage of original, thought-provoking and independent football-related literature in various forms.

The review adds to the overwhelmingly positive reception Chasing the Game has received since its release in 2014. A summary of how the novel has been received by literary critics, including media reviewers and established crime fiction bloggers, can be found here, while a round-up of what readers think of the book is available by clicking here.

The full review of Chasing the Game by footballbookreviews.com can be found here, but segments of it are below:

“In Chasing the Game Paul Gadsby provides a fictional account of the events around the robbery and the subsequent recovery of the trophy. As such the football element is only a minor thread in a book which is essentially a crime thriller.

“Gadsby provides an atmospheric depiction of London in the 1960s, where gangster Dale Blake is battling with discontentment amongst the ranks and an unhappy home life. The theft of the trophy and the hoped-for ransom money are seen by Dale as a way to sort out the problems he is encountering in his life.

“This is a read which is in parts gritty as it explores the murky world of gangsters, but which also has a softer side as it explores through the central character Dale a number of areas including family relationships, leadership, power and respect… Gadsby provides an entertaining and well-paced read in relation to a fictional exploration of the events in London before England’s finest footballing hour.”

[Top]5 essential Ian Fleming reads

Few novelists have mastered the pulsating art of thriller writing better than Ian Fleming, born on this day in 1908, but for my money he never received the critical acclaim he deserved.

Few novelists have mastered the pulsating art of thriller writing better than Ian Fleming, born on this day in 1908, but for my money he never received the critical acclaim he deserved.

Not only did he maximise a natural flair for storytelling, Fleming wrote with a finely-tuned grasp of creative prose that was by no means appreciated prior to his death in 1964, and was in fact often ridiculed by the high-brow literary elite of the day, which even included his close friends and his wife, Ann Charteris.

So, in a brief tribute to the creator of James Bond, here are five works where I feel Fleming best encapsulated his vivid mastery of espionage, betrayal and adventure, as well as his deep understanding of the human disposition.

1. Casino Royale

Fleming famously said of his work “while thrillers may not be literature with a capital L, it is possible to write what I can best describe as ‘thrillers designed to be read as literature’.”

Unfortunately not everyone agreed, and the release of Casino Royale, Fleming’s 1953 debut novel and the moment British secret service agent James Bond strode imperiously into the world, was met with mixed reviews.

Set in the opulent fictional casino town of Royale-les-Eaux in northern France, Bond takes on charismatic gambler and Russian agent Le Chiffre with the help of Vesper Lynd, one of the most conflicted female characters Fleming ever crafted, the CIA’s Felix Leiter and French intelligence operative Rene Mathis.

Skilfully utilising his wartime experiences as a prominent member of the Naval Intelligence Division, Fleming blended a breathtaking plot and sharp writing style with an authoritative voice on the sinister, fascinating life of a spy.

Dealing with themes of deception, fear and not to mention torture (one standout scene in particular), Casino Royale also casts an astute light on Britain’s position in the world at that delicate time, particularly its tense relationships with the USA and Russia in those formative Cold War years.

It’s a slick, gripping read that I’d heartily recommend to anyone yet to read Fleming’s work. Alan Ross in The Times called it “an extremely engaging affair” while The Sunday Times likened it to the style of Eric Ambler and Time magazine to that of Raymond Chandler.

The Manchester Guardian called it “a first-rate thriller” but also labelled it “schoolboy stuff” while The Listener dismissed the champagne-guzzling, wise-cracking Bond as an “infantile” creation. Not for the first time, Fleming’s intense and emotive output was unfairly looked down upon by some as populist fodder.

2. From Russia With Love

The fifth book in the James Bond series, From Russia With Love, was released in 1957 and further explored Britain’s declining position of influence in the world as the Cold War intensified.

The Soviet counterintelligence agency SMERSH plans to assassinate Bond in a way that humiliates the British Secret Service. No fools, they send a beautiful cipher clerk in as bait to draw Bond in.

Fleming’s decision to place much of the action in Istanbul and on the Orient Express gives the book an exotic edge, while further background to Bond’s private life, including his surprising levels of self-doubt, is subtly added to enhance character development.

The taut plot also includes a cliffhanger finale, with Rosa Klebb, SMERSH head of operations, kicking Bond with a poisoned blade hidden in her shoe, causing him to lose consciousness and collapse to the floor clinging for life as the book ends.

Once again there was an air of snobbery in the reviews, Anthony Boucher describing the book as having “a veneer of literacy” but US president John F Kennedy later listed From Russia With Love as one of his favourite books, not only leading to a surge in sales, but also cementing Fleming as a major author of note Stateside.

3. The Spy Who Loved Me

This 1962 novel was a huge creative gamble by Fleming, and one that he wasn’t given enough credit for. Courageously abandoning Bond for much of the book, The Spy Who Loved Me is told by a female narrator, with Bond making a late appearance in a supporting role. Needless to say, the 1977 film version starring Roger Moore contains no elements of the book whatsoever.

The gamble was even larger considering the fact that the public’s appetite for reading about a male super hero spy, and Bond in particular, had never been higher, and the Bond franchise was about to reach astronomical levels with the release of the debut film, Dr No, that summer.

But, with his health deteriorating, Fleming decided to go for broke and lead with the voice of a female stranger, perhaps with half a mind on securing that elusive intellectual acclaim.

The story centres around Canadian Vivienne Michel who, after being educated in England, returns to North America in her early 20s and embarks on a leisurely road trip. In the Adirondack Mountains in the north of Upstate New York, she spends a stormy night looking after an empty hotel shortly to close for the winter. Two thugs arrive, and are in the midst of attacking her when Bond appears, having suffered a puncture on route from Nassau to Toronto, to save the day.

The depth of characterisation Fleming achieved with his new lead protagonist was one of his finest literary successes, and he even went as far as giving Vivienne a fictional co-author credit in the prologue.

But the brave departure from standard Bond formula jarred many fans and reviewers, and Fleming’s confidence took such a knock from the book’s poor initial reception that he attempted to block all reprints as well as a paperback edition in the UK, although such a version was published after his death. Over the years public opinion surrounding this work has become decidedly warmer.

4. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service

By far the most interesting of the ‘Blofeld trilogy’, sandwiched between Thunderball and You Only Live Twice, this unique 1963 novel stands out for Fleming’s deeper unravelling of Bond’s persona.

After tracking Blofeld down to his mountain-top clinical research institute in Switzerland, Bond attempts to destroy both the centre and the resourceful villain. But the charm of this book lies in what is revealed about Bond. We read about him visiting the grave of Vesper Lynd, who had such an effect on him in Casino Royale, and he later meets and falls in love with Contessa Teresa ‘Tracy’ di Vicenzo, the daughter of a powerful crime boss.

An emotional Bond asks Tracy to marry him and so, for the only time in the Bond canon, the heroic spy ties the knot. While driving away from the ceremony, Blofeld shoots at the car from distance, killing Tracy. Bond escapes injury but is mentally scarred forever.

5. Octopussy

I’m going to finish off with a short story – Fleming wrote nine of them in the Bond series, and because I’ve already covered the best of these, The Living Daylights, in another piece on this site (7 of the most underrated short stories ever) for the sake of variety I’ll discuss the next best here – Octopussy.

Penned in 1962 but published posthumously in 1966, this intriguing story finds Bond tasked with apprehending former operative and World War Two hero Major Dexter Smythe, who’s wanted for questioning over an unsolved murder involving a stolen cache of Nazi gold.

Turning up at Smythe’s lavish Caribbean home, Bond, like us, is told the story in flashback as Smythe, sensing his time is up, tantalisingly unravels his involvement in the case. Fleming does a wonderful job of portraying a man of high standing unburdening himself, the years of guilt slipping away, and then strikes a fine and perfectly plausible connection between Bond and the murder victim, clarifying for the reader why MI6’s finest has been sent to make this arrest.

Smythe, knowing his comeuppance is due and that Bond won’t be shaken off, commits suicide by allowing his pet octopus to attack him in his own swimming pool, bringing on a fatal heart attack.

An absorbing read that carries a peculiar edge, Octopussy is a fine example of a major character dominating a short story even with a minor role – Bond’s mere presence forces Smythe’s hand.

[Top]5 sublime plot twists in crime fiction

Every reader loves a good plot twist that shocks them to the core and enriches their enjoyment of a story, but some twists have been more successful than others.

Every reader loves a good plot twist that shocks them to the core and enriches their enjoyment of a story, but some twists have been more successful than others.

The author has the responsibility to ensure the twist comes as a genuine surprise, but they must also deliver it in a plausible and elegant way that falls consistent with the story and characters the reader has bonded with.

The crime genre is a natural home for such a literary device, so here are my top 5 plot twists – or sudden shifts of momentum – that caused a revelation and propelled the books concerned to a higher level of critical and public acclaim.

Oh, and there are spoilers galore here…

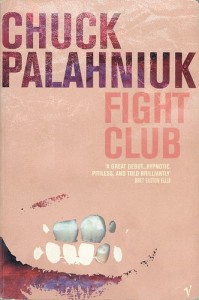

Fight Club, by Chuck Palahniuk

Quite simply one of the most shocking twists ever. This 1996 novel, reaching a far wider audience following the 1999 film adaption starring Brad Pitt and Edward Norton, delivers a sucker punch out of nowhere that leaves the reader reeling.

The unnamed protagonist/narrator, struggling with insomnia, finds relief by impersonating a seriously ill person in several support groups. He later meets charismatic extremist Tyler Durden, whose radical facade and mysterious charm fascinates him. When the narrator’s condo is destroyed in a gas explosion, he moves in with Tyler. Discovering they enjoy a fist fight as an intense form of male psychotherapy, they establish an underground bareknuckle fighting club that soars in popularity with men of similar character.

As the club evolves into a militant, anti-establishment pursuit named Project Mayhem, the narrator resolves to stop Tyler and his loyal followers from engaging in their violent sabotage operations. But his mission gets complicated when the narrator realises that he is in fact Tyler. During his bouts of insomnia, his mind had created a separate personality, Tyler becoming active whenever the narrator was ‘sleeping’. It was the Tyler persona that blew up the condo, that set up the fight club. But is it too late to stop Project Mayhem?

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, by Agatha Christie

This 1926 novel is one of Christie’s most controversial mysteries, its pioneering twist at the end shaking not only the book’s readers but also the crime fiction genre itself.

Set in the fictional English village of King’s Abbott, narrator Dr James Sheppard is invited to dine at the home of country gentleman Roger Ackroyd, who is distressed by the recent death of his lover, Mrs Ferrars. After returning home that evening, Sheppard receives a telephone call informing him that Ackroyd has been murdered.

Belgian detective Hercule Poirot comes out of retirement to investigate, Sheppard becoming his assistant. The pair discover several characters whose own distinctive secrets point the finger of suspicion at them. Poirot calls them all together to discuss the case (sound familiar?) but later dismisses them. Because he knows Ackroyd’s killer is still in the room – Sheppard.

The idea of a narrator being the murderer wasn’t entirely new, but in the hands of an expert technician like Christie, her gifts for analytical stimulation and formidable storytelling ensured the concept had never been unravelled in such a breathtaking fashion.

Before I go to Sleep, by S. J. Watson

A debut novel that became a best seller on its 2011 release, this story is beautifully crafted with a graceful finale that lives long in the memory.

In a similar premise to Hollywood blockbuster Memento, Christine Lucas wakes up every morning thinking she is a twenty-something woman with a bright future. In reality she is forty seven and suffered a terrible attack eighteen years ago that has left her unable to retain new memories.

The man she wakes up with is her husband, Ben, who tells her every morning they have been married for many years, and reminds her about her accident.

Dr Nash, a specialist in memory disorders, encourages Christine to keep a journal that helps piece her past together. As more flash memories emerge, the details appear inconsistent with what Ben and Dr Nash are telling her. During a short vacation with Ben, Christine finds some pages torn from her journal in his luggage. It turns out that Ben is not Ben, but a man named Mike with whom Christine had a brief affair with eighteen years ago. Christine suddenly remembers that it was Mike who attacked her.

Watson makes the reader question each of the characters throughout, while the smart use of the journal allows us to discover things at the same pace as Christine. The author weighs the balance perfectly between portraying Christine’s emotions and relaying the conspiracy theories that keep the story motoring along.

Tell No One, by Harlan Coben

This 2001 book was a major breakthrough for Coben, his first novel to appear on The New York Times Best Seller list and adapted into a French film in 2006.

Paediatrician David Beck receives an email that makes him believe his wife Elizabeth is alive, eight years after they were both attacked by two men, leaving David seriously injured in a lake and him thinking Elizabeth had been killed.

As he tries to find out if she really is alive, David discovers that Elizabeth had been wrongly blamed by a local man, Griffin Scopes, for the death of his drug dealing son. Griffin had then paid two men to kill Elizabeth and David, who after the attack was pulled from the water by a homeless man hiding from the authorities.

David then learns that Elizabeth’s father, Hoyt, killed the two men who attacked them and convinced Elizabeth to leave the country for her safety, leading authorities to believe she was the victim of a serial killer.

When the bodies of the two hired killers are discovered, Elizabeth realises Griffin will question her death, so she returns to the USA hoping to reunite with David. But she’s discovered and the situation hurtles towards a brutal conclusion.

Twists and turns on this scale are very challenging to pull off, but in Coben’s hands the action unfolds with a deft sense of drama and credibility.

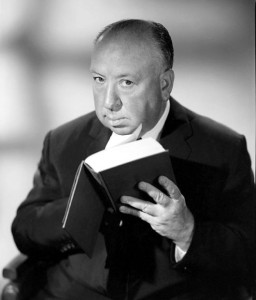

Psycho, by Robert Bloch

A renowned 1959 thriller that was eclipsed by Alfred Hitchcock’s movie adaptation a year later, this novel deserves to go down as a crime classic.

Mary Crane is on the run after impulsively stealing $40,000 from a client of the real estate company she works for. She stops at a small motel in Fairvale, California, run by middle-aged bachelor Norman Bates and his temperamental mother. While Mary takes a shower that night, a figure resembling an old woman sneaks in with a kitchen knife and butchers her to death.

Mary’s sister, Lila, and boyfriend Sam Loomis investigate. At the Bates family home overlooking the motel they discover Mrs Bates’ mummified corpse in the fruit cellar. A figure rushes into the room wielding a knife – Norman Bates, dressed in his mother’s clothes.

A psychiatrist examines Bates and learns that, years before, he had poisoned his mother and her lover in a jealous rage. To suppress the guilt he had developed a split personality in which his mother became an alternate self, which abused and dominated him as Mrs Bates had done in real life.

The novel is fast-paced, terrifying and utterly disturbing, capped off with this shocking twist that captivated readers and opened America’s eyes to serious mental health issues.

Enjoyed reading about stunning plot twists? Here are some more books with great surprises that nearly made my top 5 list:

The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald

London Boulevard, by Ken Bruen

Gone Girl, by Gillian Flynn

The Sicilian, by Mario Puzo

Shutter Island, by Dennis Lehane

How Jake Arnott revived British crime fiction

March 11 is a significant date in my world – not least because it’s my wedding anniversary, but it also marks the birth of one of the most important British crime writers of the last 15 years, Jake Arnott.

March 11 is a significant date in my world – not least because it’s my wedding anniversary, but it also marks the birth of one of the most important British crime writers of the last 15 years, Jake Arnott.

Today Arnott turns 54, and I can still remember the buzz I felt when reading his 1999 debut novel The Long Firm that sparked a magnificent – and much-needed – revival in quality, thought-provoking British crime fiction.

Arnott was never going to be a writer who would provide us with another clichéd, world-weary detective that would run on and on for years in cosy annual instalments. And boy we were tired of those. No, The Long Firm was a rousing one-off (just like his other five books since), exploring the tale of charismatic, homosexual nightclub owner and racketeer Harry Starks through the eyes of five people that knew him in 1960s London.

Those five different points of view gave us a finely executed deep character analysis of Starks, all woven within a subjective, forceful, tender and ultimately convincing narrative. Those perspectives came from a young boyfriend of Starks, a female singer and love rival, an old-school backbencher in the House of Lords, a wayward criminal on the edge of darkness, and finally a sociologist in the 1970s, giving the overall story a diverse, grand scope.

The characterisation was sublime, as was the period detail (it included perceptive references to some real-life personalities of the time including Judy Garland and the Kray twins), Arnott excavating the cultural minutiae of the era to give us an evocative feel for the bleaker side of the swinging sixties.

But it was The Long Firm’s magnetic, lyrical prose that made the novel stand out, that took the gritty British gangster genre to a higher level, blending a gripping storyline with genuine splashes of literary fiction. Good literary fiction, that is. Worthy, skilful fiction spawned from the soul and aimed at the heart.

Crime fiction was no longer just about a haggard, vulnerable cop having several stones thrown at him by professional enemies and being weighed down by personal demons before bravely exposing – and defeating – the arrogant criminal. No longer about conventional plot-led tales (albeit well-written and tension-fuelled ones) constructed to be read on long flights.

The literary ambition of The Long Firm served as a groundbreaking text for both writers and readers, possibly even agents and publishers as well. It gave writers who wanted to explore a world beyond another Rebus or a serial killer the chance to reach that brave new territory, that higher plane where character and prose – in terms of length and style – could be the preserve of their imagination, and engineered to however their particular story demanded. Not bound by the industry guidelines and perceptions of what sells and what doesn’t.

Not that those guidelines aren’t valuable (any industry needs to rely on past buying habits to build for the future), but the timing of Jake Arnott’s breakthrough was important. It allowed writers that followed the opportunity to forge their own creative path, to trust their own instincts and senses, and encouraged agents and publishers to take a chance on more decadent, quirky crime fiction that didn’t necessarily fit into a style and format they were previously committed to.

After The Long Firm we saw a wave of idiosyncratic British and Irish crime writers – authors who dedicated themselves to crafting and maintaining a powerful writing style faithful to their own tastes and desires – break through. The likes of Adrian McKinty, David Peace, Ray Banks, Allan Guthrie, Stav Sherez, Simon Lelic and Neil Forsyth all launched successful careers, while authors such as Ken Bruen, Nicholas Royle, Peter Guttridge and Gene Kerrigan achieved higher recognition. The range of contemporary crime writing had expanded way beyond the formulaic detective mystery – existential noir, irony, humour, ferocity, fact-fiction intrigue and horror all stood loud and proud as major pulse points within this fascinating genre.

Arnott’s second book, He Kills Coppers, was released in 2001 and carried much of the intimate verve and sensual swagger we saw in The Long Firm. Based on one of Britain’s most infamous true crimes, the 1966 murders of three Met police officers in Shepherd’s Bush (the name of the real killer, Harry Roberts, was changed to Billy Porter), He Kills Coppers was a huge critical and commercial success and paved the way for Arnott to carve a successful career that has been carried out largely at his own pace and to his own liking.

Not one to put himself under undue pressure by signing a contract that committed him to churning out a new release every year, his third book, True Crime, came out in 2003, telling the story of a dead gangster’s daughter seeking the truth surrounding her father’s murder (linked to The Long Firm). Arnott left the criminal underworld behind in Johnny Come Home (2006) to write about a 1970s glam rock star and the anarchist group ‘The Angry Brigade’, and shifted focus even further with The Devil’s Paintbrush (2009), detailing a 1903 encounter in Paris between the occultist Aleister Crowley and former British Army officer Sir Hector MacDonald, under threat of court martial following allegations of homosexuality, on the eve of the soldier’s suicide.

In 2012 Arnott released The House of Rumour, a conspiracy tale involving WWII spies (featuring Ian Fleming), science fiction writers in 1950s California and the new wave music scene in 1980s Britain. Again the mixture of real-life figures and fictional characters resulted in a dazzling, if sometimes baffling, effect in a book that was hailed as a time-spinning, genre-fusing, continent-hopping classic.

Who knows what’s next, but one thing is for sure – Jake Arnott is an author who has made full use of his intellect and passions to skilfully explore the themes of masculinity, class, sexuality, ambition and repression. And through his gifts for characterisation and innovative prose, he has given us some smart, enjoyable literature that proved forceful and eloquent writing can merge as one.

[Top]Chasing the Game – what the readers think

The reading public always passes the ultimate judgement on a book, so I thought I’d highlight some of the comments left by readers on the Amazon review page of my debut novel, Chasing the Game.

The reading public always passes the ultimate judgement on a book, so I thought I’d highlight some of the comments left by readers on the Amazon review page of my debut novel, Chasing the Game.

For those of you who would like to see how the book was received by literary critics, please click here to see what media reviewers and established crime fiction bloggers thought of Chasing the Game.

But here are some quick snippets from a selection of verdicts from those all important readers…

“Fantastic 1960s detail . . . can’t remember the last time I enjoyed a debut novel more.

Too many gangster books can slip into caricature, but the highest praise I can give is that so much of the authentic period detail and Gadsby’s sharp dialogue evoked memories of when I discovered Jake Arnott’s series of books more than a decade ago.

It would be interesting if it could be dramatized for the 50th anniversary of the theft in 2016.”

Paul Richardson

“What a fantastic book . . . The amount of research put in is immense, to nearly every detail. 60s gangsters and the rest of the trimmings, but with a clarity to the story, and writing. I can’t recommend it enough.”

David Hardy

“The characters’ personalities all come alive and keep you guessing at what their fate will be. The story moves along at a good pace and makes the book difficult to put down. This is not just for the guys.”

Gillian Brown

“Compelling, original and eminently readable. The story skilfully merges fiction and the real life events surrounding the actual theft of the Jules Rimet Trophy in 1966. This is a fast paced mystery with an atmospheric setting that succeeds in depositing the reader into the vibrant, rapidly changing London of the 1960s. The book will appeal to all mystery and crime aficionados.”

Benignus

“I loved this book. It’s a real page turner. Beautifully plotted, with lots of twists and turns. The characters are very well drawn. The dialogue crackles and fizzes. The mixture of tension, humour and, at times, almost farce is really deftly judged and pulled off. Highly recommended!”

L.G. Williams

“A great read, couldn’t put it down. As I was in my late teens at the time of the ‘66 World Cup and the theft of the World Cup is still vividly etched in my memory. Paul’s account of the theft and subsequent recovery of the iconic trophy, whilst fictional, is very plausible given the gangland culture that existed in East and South London at that time. Brought back to life those black and photos that graced the tabloids the day after Pickles discovered the package in the hedge of that front garden. A brilliant first offering from a talented writer.”

Lillywhite

“Well worth a read! Full of well researched detail, and the twists in the story keep you gripped until the very end. It’s not just a book about a football trophy, it’s so much more and I would highly recommend it to everyone.”

ABM

“Fantastic book, I couldn’t put it down. Well written and researched and a great twist in the book. I cannot recommend it highly enough. Hope it’s not too long before the next one!”

Neil Mason

“Paul Gadsby has created a very authentic 60s London and a crime firm that feels as though it really could exist. You will want the main character to succeed, despite being a criminal! And it ties in very well to real life events. A brilliant read.”

Paul Green

“A very plausible storyline depicting a historical moment of British history.

A fantastic read. Not only a very imaginative depiction of what could have happened when the World Cup was stolen but also an excellent underlying story of a criminal firm led by Dale. I was really impressed with how I could empathise with each of the characters in their own right.

This would make an excellent television drama which I feel would appeal to not only football fans but a wider audience.”

Victoria Vickers

James Sallis – a tribute

This week marks the 70th birthday of one of the finest – and one of my favourite – contemporary writers, James Sallis.

This week marks the 70th birthday of one of the finest – and one of my favourite – contemporary writers, James Sallis.

A crime novelist, poet and musician, Sallis, younger brother of philosopher John Sallis, cultivated a reputation as an influential writer in the 1990s with his Lew Griffin series of books set in New Orleans. But it was his 2005 neo-noir thriller Drive that catapulted him to global literary acclaim and was adapted into a 2011 film of the same name, starring Ryan Gosling, Carey Mulligan and Christina Hendricks.

Sallis’ inimitable talent comes from a precious devotion to his craft. For many years he has combined his own work with teaching novel writing at Phoenix College in Arizona, while he also keeps his creative juices flowing by playing with his string band, Three-Legged Dog, his instruments of choice including the guitar, French horn, fiddle, mandolin, sitar and ukelele.

His work first came to my attention courtesy of the terrific support he has received from astute British indie publisher No Exit Press, who published his ex-con-turned-cop John Turner series as well as his Griffin books, a spy novel Death Will Have Your Eyes, along with Drive and the sequel to that classic, Driven.

Often referred to as ‘a crime writer’s crime writer’, Sallis is admired for his Hemingway-esque economy of language and the emotional depth of the fictional worlds he creates, amplified through the engaging philosophical outlook of many of his characters.

His back catalogue deserves to be swamped with praise, but it’s Drive that I’d like to focus on here. A gripping story of a young man abandoned from an early age and searching for an identity, he utilises his one passion – driving (the character is only ever referred to as ‘The Driver) to become a prolific Hollywood stunt driver by day and a wily getaway driver for the LA criminal underworld by night.

Paying homage to the successful style conventions of the noir genre, Sallis uses just 157 pages to pen a work dripping with existential minimalism, taut plotting, brutal hostility and sharp-witted dialogue, the actions of the intensely conflicted characters driven by the heart and a longing for their sense of place in the world.

One tool that Sallis maximises in a unique way is backstory. Interspersed at relevant points throughout the book, pieces of The Driver’s past are delicately presented to the reader in a way that skilfully hooks the reader in. Some of these passages aren’t as terse as you’d expect in a noir novel, but Sallis’ ability to always cut straight to the heart of the matter means you don’t feel like you’re being dragged away from the central narrative.

Although the book has its violent outbursts, none of this is graphic. The rich, flowing narrative, reminiscent of 50s noir but also laced with a 70s cult movie feel, keeps the pages turning. And despite the sharp detail offered in the flashbacks, The Driver remains a mysterious protagonist – like the book itself he is compelling, stark and beautiful.

‘I find Driver fascinating,’ Sallis once told GQ. ‘I wanted to make him this iconic, almost mythic American character . . . he accepts that the violence is who he is, what he does and he learns to embrace that.’

For me Drive remains James Sallis’ finest work; quaintly witty and utterly readable, it’s a literary masterpiece that elevates Sallis into the ranks of noir legends such as Jim Thompson, Graham Greene, James M Cain, Cormac McCarthy and even the Coen brothers.

As Sallis himself wrote in his essay, Standing by Death: ‘The deepest, most engaging and damaging moments of my life become notes, then pages and, finally, books. This is the purpose my life has taken. Maybe in the end it’s only that I want to leave a mark, something to show that I’ve been here.’

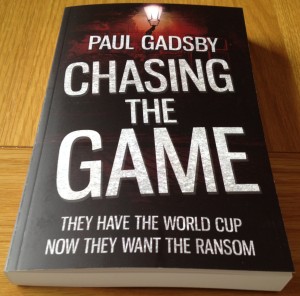

[Top]Christmas sales surge for Chasing the Game

The festive period is always a buoyant one for the books trade and I’m delighted to reveal that Chasing the Game is no exception, my debut crime thriller enjoying a rise in sales in recent weeks.

The festive period is always a buoyant one for the books trade and I’m delighted to reveal that Chasing the Game is no exception, my debut crime thriller enjoying a rise in sales in recent weeks.

Both the paperback and ebook versions of the book have seen a sharp increase in sales, with people seeing the book as an ideal stocking filler Christmas gift.

The paperback, currently priced at £6.53 on Amazon, and the ebook at just £1.99, represent fantastic value for those wishing to give their friends or family a gripping, fast-paced read to enjoy.

It beats toiletries or a naff pair of socks, anyway.

Chasing the Game is a unique fictional depiction of the real-life theft of the Jules Rimet Trophy (the original football World Cup) in London in 1966, a crime which remains unsolved. To read more about the book and the true-life crime that sparked its narrative, please click here.

[Top]The 10 best books that inspired Hitchcock films

As a huge fan of Alfred Hitchcock’s movies, I’ve always been fascinated as much by the novels that inspired his directorial work as I have his famed skills for generating treasured moments of cinematic suspense.

As a huge fan of Alfred Hitchcock’s movies, I’ve always been fascinated as much by the novels that inspired his directorial work as I have his famed skills for generating treasured moments of cinematic suspense.

With that in mind, I have compiled my favourite – and what I consider the most accomplished – novels that Hitchcock later used as a basis to make a film. For the sake of sincerity, I’ve included some of the bigger-name titles that Hitchcock became best known for and just can’t be ignored, but I’ve also dug a little deeper to highlight some more unfamiliar works that deserve a mention.

Happy reading…

10. Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square

Written by journalist and crime reporter Arthur La Bern in 1966, this relentless novel was used by Hitchcock as the basis for his 1972 classic Frenzy.

The book tells the story of Bob Rusk, a sexual predator and serial killer in central London, but circumstantial evidence leads the police to prosecuting Rusk’s friend, Dick Blamey, for the string of crimes known as ‘the necktie murders’. Always partial to a tale of an innocent man getting stitched up, it’s easy to see what attracted Hitchcock to the story.

The movie represented an important chapter in the director’s legacy, seen as a triumphant return to Britain in what was his first film set there for more than 20 years (and only this third made in Blighty since moving to Hollywood in 1939). It also ended up being the penultimate film of Hitchcock’s career.

He asked Anthony Shaffer to adapt it for the screen, and there were some significant changes made from the book’s narrative. The light-hearted domestic scenes between the meticulous Inspector Oxford and his wife were entirely new creations (presumably Hitchcock wanted them to serve as a change of pace and tone from the brutality of the murders). The film was set in the era it was made – the early 1970s – while the novel takes place shortly after the Second World War (hence the title, taken from a line in the song ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’) and Blamey has an interesting backstory ignored in the film. In the novel he is a Royal Air Force veteran who feels guilty about his active role in the fire-bombing of Dresden, and his drunken references to his ‘killing’ past when first being interrogated by police about the necktie murders contributes to his unjust arrest.

La Bern was not a fan of what Hitchcock and Shaffer did with his story. In a letter to The Times, he called Frenzy a ‘distasteful film’, criticising the dialogue as ‘farce’ and adding: ‘I would like to ask Mr Hitchcock and Mr Shaffer what happened between book and script to the authentic London characters I created. Finally: I wish to dissociate myself with Mr Shaffer’s grotesque misrepresentation of Scotland Yard offices’.

9. The Manxman

One of writer Hall Caine’s greatest successes, this 1894 novel sold more than half a million copies and was translated into 12 languages.

Set on the Isle of Man, the book depicts a powerful love triangle between Kate Cregeen and her two friends, the illiterate but good-hearted Peter Quilliam, and the well-educated and sophisticated Philip Christian.

Notable for its regular use of Manx dialect unique to the Isle of Man, faithfully executed by Caine through unusual Manx Gaelic spellings, grammatical structure and phrases, the book received widespread critical acclaim, especially from high society. Britain’s Prime Minister of the day, Lord Rosebury, said: ‘It will rank with the great works of English literature’.

The novel was adapted twice for the stage and turned into a silent film by George Tucker in 1917 before Hitchcock developed it into his final silent movie in 1929.

Filmed almost entirely in the small Cornwall fishing village of Polperro, Hitchcock’s version was highly praised, his gripping portrayal of the love triangle emitting some of his most emotive characterisation and strongest imagery to date. Which is more than what the man himself thought of this work. Hitchcock later told Francois Truffaut it was ‘a very banal picture’, adding the ‘only point of interest about that movie is that it was my last silent one.’

8. The Thirty-Nine Steps

Now we’re on to one of the big hitters. This high-octane, pacey novel with its lethally sharp prose reads as smoothly as any sparse, contemporary thriller – Christ knows how rapid it must have felt on its release in 1915.

By far the most famous novel by Scottish author John Buchan, The Thirty-Nine Steps has never been out of print since. It was in fact Buchan’s 17th published book, and catapulted him from a promising 39-year-old writer into a best-selling author of highly-acclaimed thrillers and adventures over the following two decades.

Despite the book perhaps being most remembered for its glorious evocation of the rolling Scottish countryside, of its 10 chapters only three and a half are actually set in Scotland. Main protagonist Richard Hannay (wonderfully played by Robert Donat in Hitchcock’s 1935 adaptation) offered the reading public in the first year of WW1 something relatively fresh; a physically dynamic anti-hero, cool and brave with the intellectual and emotional prowess that enabled him to turn detective under pressure (skills that earned him a leading role in four further Buchan books) while still maintaining a stiff upper lip.

Although the book was a pioneer of the ‘man-on-the-run’ archetypal thriller that would become a much-used plot device, Buchan’s enthusiasm for inserting unlikely events into the plot that the reader would only just be able to believe does give the book a somewhat fantastical edge, but it’s a barnstorming read nonetheless.

Hitchcock’s film does divert somewhat from the book, creating the music hall scene and the two major female characters for cinematic effect. In the book the 39 steps refer to literally that, while in the movie the 39 steps is a clandestine group of spies.

7. The Lodger

Prolific London-born novelist Marie Belloc Lowndes is said to have gotten the idea for this story after overhearing a dinner conversation where a guest was telling another that his mother’s butler claimed to have once rented a room to Jack the Ripper. That was the spark that eventually led in 1913 to her releasing The Lodger, a fictional take on the gruesome Whitechapel murders of 1888. It sold more than a million copies.

The style of the story is pure Hitchcock – the horror builds slowly and skilfully as landlords Richard and Ellen Bunting gradually begin to fear that a recent lodger they’ve taken on upstairs in their home, a Mr Sleuth, could be the mysterious killer of several local women.

Using the story, as well as the play ‘Who is He?’, a comic stage adaption of the novel co-written by Belloc Lowndes and playwright Horace Annesley Vachell, Hitchcock delivered one of his finest silent movies in 1927, titled ‘The Lodger: A story of the London Fog’. Oozing with psychological suspense, menacing camera angles and claustrophobic lighting, the film was also Hitchcock’s first foray into sexual fetishism and psychodrama.

Interestingly, Hitchcock wanted the film to end with ambiguity over whether the lodger was the serial killer, but he later claimed the studio, Gainsborough, wouldn’t let popular leading man Ivor Novello be considered as a villain. ‘We had to change the script to show that without a doubt he was innocent,’ Hitchcock said.

6. Before the Fact

Written in 1932 by Anthony Berkeley, under the pen name Francis Iles, this bold novel was adapted by Hitchcock into his 1941 film Suspicion.

Far from penning a popular whodunit, Berkeley ensured the readers of Before the Fact knew who the villain was pretty early on. Johnnie Aysgarth has married Lina McLaidlaw for her family’s money. Over the years that follow Lina gradually learns that Johnnie is a compulsive liar, thief, embezzler, adulterer and in fact plans to murder her. At the end of the novel, which has spanned 10 years, Lina, flu-stricken and mentally unhinged but still desperately in love with her husband, swallows a cocktail she knows Johnnie has poisoned. Her death is imminent, but not conclusive, when the book ends.

Hitchcock’s film covers much of this dark and suspenseful mood, but differs from the book in that Johnnie’s ‘murderous’ intentions are portrayed as a product of Lina’s imagination. In a similar predicament to The Lodger, there was also apparent studio interference with the plot ending, with RKO Radio Pictures said to be not all that keen on having one of Hollywood’s most heroic actors, Cary Grant, being shown on screen as a devious killer. Despite not being able to play Lina in the emotionally complex and compelling ending described in the book, Joan Fontaine’s depiction of the character in the film was strong enough to earn her the 1941 Academy Award for Best Actress.

5. Psycho

I suppose it’s fair to say the film has eclipsed the novel on this one. Robert Bloch’s 1959 book was an instant hit, influenced from the pulp principles of the day – Psycho is fast-paced, terrifying, captivating and utterly disturbing, all laced with a healthy dose of murder, madness and mayhem.

Hitchcock’s seminal movie of the same name came out just a year later, the speed of the adaption perhaps an indication of how powerful a novel Hitchcock regarded it to be (‘Psycho all came from Robert Bloch’s book,’ he said, albeit nine years later). It’s one of the director’s most faithful adaptions, the narrative skeleton of the book retained throughout the feature, with suspense, mystery and horror leading the way.

One difference was Hitchcock’s clarity of focus when it came to driving the story through certain characters’ perspectives. Bloch was happy to shift the point of view throughout his narrative; the opening chapter is from Norman’s perspective, the second Mary’s (who was called Marion in the film), the third is split between the two of them, and we’re back in Norman’s head in chapters four and five. Some of the latter chapters are written in the style of neutral third person. Hitch had a clear agenda of who he wanted the audience to bond with; we’re solely with Marion from the start until she meets her maker in the shower; then it’s largely Norman.

In Bloch’s chapters written from Norman’s POV, the writing is exceptional. His blackouts appear so genuine that the reader is compelled to believe that his jealous mother truly is Mary’s killer.

4. Marnie

Another example of great, daring literature, Winston Graham’s psychological thriller Marnie is a hugely suspenseful and captivating read.

A prolific author well known for his series of Poldark historical novels, Graham released Marnie in 1961 to great acclaim but also a fair bout of controversy. The title character is a beautiful embezzler (played by Tippi Hedren in Hitchcock’s 1964 film) whose life of crime was sparked by a traumatic incident in her early childhood that she and the audience only get to truly understand at the end of the story.

After getting caught stealing from her employer, Mark Rutland, who also happens to be in love with her, Marnie is forced into marrying him in order to avoid jail. The marriage evolves into a complex but gripping web of deception, misinterpretations, mistakes and disputes, including a rape scene. Mark feels he loves her and is doing the right thing to get Marnie over her psychological problems; Marnie feels she was blackmailed into the marriage.

As the plot thickens, the book becomes a crime novel less centred around crime but by the mystery of Marnie’s secret past (and that of her mother’s), her core identity, and the complex issues of psychiatry. Written as a first person account by Marnie, the book is a finely-tuned introspective character piece that Hitchcock was fascinated by.

So determined to keep the divisive rape scene in his 1964 movie, Hitchcock dismissed screenwriter Evan Hunter from the project, who pleaded that the sequence be dropped because the audience wouldn’t bond with the male lead (played by Sean Connery). Replacement Jay Presson Allen shared Hitchcock’s keenness to include the scene.

There were some alterations made from the book though; Hitchcock changed the setting from England to the USA, thus losing the quintessential English ambience of the book according to some critics, a key character from the book, a lechy executive who pursues Marnie, is omitted altogether and the unravelling of Marnie’s childhood trauma that became the source of her emotional problems is a lot more simple and optimistic than the darker, more complex version in the novel.

3. The Rainbird Pattern

Plymouth-born thriller writer Victor Canning published 61 books in his lifetime, but one is widely regarded as by far and away his best – The Rainbird Pattern, winner of the Crime Writers’ Association Silver Dagger in 1972.

Elderly spinster Grace Rainbird, trying to bring missing elements of her family together before her time is up, promises spirit medium Blanche Tyler a large sum of money to locate her illegitimate nephew Edward Shoebridge. Blanche and her boyfriend, George Lumley, go desperately looking for Edward, who so happens to be living under a different name and co-ordinating several kidnappings of prominent officials, with his next project likely to rake in his largest ever ransom – the abduction of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

This split-level story is woven together with deft skill, Canning building the suspense and heightening the violence beautifully before unleashing an unpredictable ending. The plot is so seamless and commanding that it’s fair to say this is a prime example of a book triumphing over a Hitchcock film.

Titled ‘Family Plot’, Hitch’s 1976 movie turned out to be his final motion picture before his death four years later. The setting was switched from the south of England to southern California, and the charismatic features of Blanche and her jack-of-all-trades quirky partner Lumley were magnified so the tone of the film came across as more of a black comedy. Although personally I’ve always thought Family Plot an invigorating and much under-rated film, its reception in no way matched the glowing reviews attributed to The Rainbird Pattern.

2. Rebecca

When it comes to linking Hitchcock with fiction, Daphne du Maurier is pretty much literature royalty. Her short story ‘The Birds’ went on to provide the basis for one of the director’s most iconic hits, but her glorious 1938 novel Rebecca goes down as a genuine literary masterpiece.

An outstandingly evocative opening sentence (‘Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again…), the razor-sharp description of a haunting fictional estate, a compelling combination of lead characters and a fascinating mystery all add up to a classic gothic romance thriller.

‘Very roughly, the book will be about the influence of a first wife on a second,’ wrote du Maurier in her notes. ‘Until wife 2 is haunted day and night… a tragedy is looming very close and crash! Bang! Something happens.’

Her tale of jealousy, bitterness, identity, mystery and secrets broke the mould of themes being explored by her contemporaries of the day. She sidestepped issues such as war, religion, poverty, art and existentialist streams of consciousness to thread together a more simple narrative about love, adventure and mystery and the reading public lapped it up, its appeal enduring to this day.

Hitchcock did a marvellous job adapting it for the screen in 1940, his first project after moving to America. As well as being technically brilliant (it won the Academy Award for Best Picture and Best Cinematography) the film largely maintained the emotional drama of the book. There was one plot detail change though; in order to comply with the Hollywood Production Code, which outlined that the murder of a spouse had to be punished, the book’s revelation that Max killed Rebecca had to be altered. He considers killing her as she taunts him into believing that she’s pregnant with another man’s child, but she is in fact suffering from incurable cancer and has a motive to commit suicide and punishing Max from beyond the grave, so her death is declared a suicide.

1. Strangers on a Train

Before Patricia Highsmith famously created the anti-hero Tom Ripley, she penned the breathtakingly sharp, taut and dark ‘Strangers on a Train’ in 1950, which remains one of the finest blueprints of noir fiction to this day.

Architect Guy Haines is desperate to divorce his unfaithful wife, Miriam. While on a train he meets coarse alcoholic Charles Anthony Bruno, a sociopath who suggests they ‘exchange murders’. Bruno will kill Miriam if Guy offs Bruno’s father; neither of them will have a motive and the police will have no reason to suspect either of them. Guy thinks it’s a joke, but the deranged Bruno moves first and kills Miriam. Panic, guilt, a chaotic game of cat and mouse, and further tragedy all follows.

Highsmith flourishes in drawing the reader in by stacking complications on top of each other as the stakes rise, while the book also serves as a skilful examination of the allure of chance meetings, and of why it seems so much easier for us to unburden ourselves to strangers, to let our guard down in unexpected moments of intimacy.

Hitchcock’s 1951 adaption received deserved praise as a creative force in its own right, but there were flaws. Hitch later admitted to Francois Truffaut that casting Farley Granger as Haines was a mistake (‘I would have liked to see William Holden in the part because he’s stronger’). The character of Bruno, meanwhile, was softened into more of a dandy charmer, while he also dies in a climactic scene on a merry-go-round rather than in a boating accident as he does in the book.

The homoerotic subtext – hinted at in the novel – is expressed more vividly in the film, possibly because Hitchcock thrived in subtly developing gay characters in his 1948 feature Rope (also starring Granger), and enjoyed presenting his audiences with sexually ambiguous characters.

Highsmith praised Robert Walker’s performance as Bruno, but wasn’t best pleased with the decision to turn Guy from an architect into a tennis player, nor with the fact that Guy does not, as he does in the novel, go through with murdering Bruno’s father.

[Top]Standalone books v series

As you can see from my influences page, many of my favourite books are standalone novels, but there are also some works that form part of a series.

Many a literary agent/editor/publisher will tell you that, particularly with crime fiction, long-running serials sell much better than standalones. Beginner writers are continually told by industry insiders that, if they want to break into the market, they stand a much better chance if they pen a manuscript ensuring the main character will return (preferably on many occasions) rather than fashion a one-off tale.

But why is this? Why are the series more appealing to readers and therefore more successful in the marketplace? Here are my thoughts, analysing the pros and cons of both standalones and series.

Standalones – the pros

By their very nature, standalones generally depict a very passionate story. The author has composed the tale based on a burning theme they wanted to pursue, a poignant story they wanted to unravel and a certain message they wanted to transmit to the reader. And they have been free to express that story in any way they see fit, tying up any loose ends (to an ultimate conclusion) if they wish, exploring any theme or location to the very limit, knowing they or their characters will never go down this road again. The shackles aren’t as much off; they were never on in the first place.

Authors can also lead their main protagonist down any dark alley they want to, even if the outcome proves fatal. The reader is on edge because they know that the character they’ve related to and connected with faces any degree of peril. The writer is doing it their way; they are pulling all the strings because they are under no pressure to sustain any part of the story or a character for a future instalment.

The authors are writing with their hearts, holding nothing back. Fire is in the belly as well as the fingertips as they unleash their saga. Whenever a media outlet releases a list of the greatest (or most popular) novels of all time, standalones are always there standing proud. For Whom the Bell Tolls, Catch 22, David Copperfield, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Day of the Jackal, The Killer Inside Me, The Great Gatsby, American Psycho, Scoop, Disgrace, Libra, The Road, No Beast so Fierce and many, many more. Works that carry a central emotive core and bare the author’s soul; unbridled creations and unique artefacts.

Standalones – the cons

Imagine if Ian Fleming, having written his heart out on his debut novel Casino Royale, had left James Bond at that point and moved on to another project, 007 confined to history in 1953. Standalone books provide us with great high-stakes tales but there’s the downside that stopping at one story prevents further development of a fascinating character, denying us the prospect of enjoying this protagonist taking on more challenges and allowing us to bond with them further. There’s no doubt that the huge cultural impact certain recurring characters have had on the world (Bond, Sherlock Holmes, Philip Marlowe et al) has done wonders for crime fiction and duly rewarded their authors with much deserved adulation.

Another point to consider here is that sometimes a standalone can be too long (Don DeLillo’s Underworld breached into this territory, as did Against the Day by Thomas Pynchon), possibly to the extent that you feel the author probably considered splitting it into a mini-series somewhere along the way but stuck with it anyway. And sometimes the total freedom an author enjoys with a standalone can lead to self-indulgence and a story/theme that winds out of control, but in a trade that depends on huge reserves of creativity and bravery, that’s often a small price to pay.

Series – the pros

Within the context of a series, particularly a long-running one, absorbing characters can be further enriched so they become legends, both literary and cinematic. There is plenty of room in standalones to develop and focus on characterisation (as there is setting and plot) of course, but with a series we just get to spend more time with our heroes, or at least people we’re fascinated by and have formed a connection with.

Another good thing about serials, especially in crime fiction, is that the cream of writing talent often rises to the top; series formats have allowed some magnificent writers to forge thoroughly deserved successful careers. Not many publishers dish out multi-book deals to poor writers. The likes of Patricia Highsmith (Thomas Ripley), Ian Rankin (Rebus), Mark Billingham (Thorne), Ken Bruen (Jack Taylor), James Sallis (Lew Griffin & The Driver), Adrian McKinty (Sean Duffy & Michael Forsythe), James Lee Burke (Dave Robicheaux), James Crumley (Milo Milodragovitch & C.W. Sughrue) and Ray Banks (Callum Innes) have all developed as writers over the course of sticking with their returning characters, the pressures of meeting their regular instalments perhaps forcing them to harness their craft in a quicker – and ultimately more confident way – than they otherwise would have done.

Serials also offer authors the opportunity to write a smartly conceived mini-series based mainly on theme rather than one principal character. With these each book is often significantly different in terms of timeframe or minor characters becoming major ones in the next book and vice versa. David Peace’s Red Riding quartet would fall into this category, a wonderful series that wouldn’t have been anywhere near as powerful as a standalone, nor a long-running series. James Ellroy’s LA quartet and Underworld trilogy also spring to mind here, as do Scott Phillips’s The Ice Harvest and The Walkaway, the narratives of those two connected works separated by 10 years.

Series novels also tend to get talked about more in social circles (so I’ve noticed anyway), allowing more opportunities for readers to share their experiences. An extensive, consistent body of work seems to bring people together more than standalones appear able to, and anything that gets people talking about reading, whether it’s at home, work, the beach or on social media, is a positive thing.

Series – the cons

The downside of an author under pressure to publish an annual instalment of a long-running series is of course the danger that they end up just churning them out. Just as their main character may have helped that author achieve fame, the process can also push them over the edge, their creative forces crashing and burning. Pumping out a novel a year to meet marketplace pressure can be a trap to penning prose unworthy of the writer and their initial ambitions, and that’s a real shame.

There’s also the danger of too many new writers feeling they have to launch their career with a main character that has ‘plenty of legs’, which all too often leads to the creation of a cliché-ridden detective we’ve all read enough of. You know the type; divorced, has a troubled relationship with his teenage son/daughter who’s growing up too fast, puts his work before his health and lifestyle, he’s the only one who despises corporate suits and bureaucracy, he unwinds in the winter evenings by listening to music anyone under 35 would scoff at, with a stiff drink in his hand. And the evil activities of each particular rival he encounters eventually results in the duo facing off in a duel, where the arrogance of the criminal leads to victory for the humble hero.

The readers lose out big time here. Not only can the returning character lose their appeal, but the plot can also lose its punch. Let’s face it, as the stakes rise in the final third we always know the main character will get out of this latest scrape relatively unscathed because they’ll be back for another adventure next year.

An example of an author who made his name with a solid series but broke free of the format to express himself in standalones is Dennis Lehane. After five instalments of blue collar detective duo Patrick Kenzie and Angela Gennaro, he pulled himself away to write Mystic River (later adapted into a Hollywood blockbuster) and then Shutter Island (ditto), two superb one-off thrillers that were both critically acclaimed and commercially successful.

Series are obviously easier to market. The industry loves them, often to the extent that a new release is promoted as a series right from the off. The first time I saw publicity for Malcolm Mackay’s debut novel The Necessary Death of Lewis Winter, it was labelled as the first instalment of ‘the Glasgow trilogy’. Almost as if his agent pitched the debut manuscript to a publisher who said “Forget it – unless your guy’s got two more up his sleeve, then I can call it a trilogy and I’ll have something to sell”.

David Peace’s ‘Tokyo trilogy’ was marketed as such on the release of the first instalment in 2007. After releasing the second in 2009, Peace drifted away from the concept and wrote Red or Dead, his standalone football novel about the late Bill Shankly. At the time of writing (September 2014) there’s still no sign of the final part of the Tokyo trilogy. Perhaps a sign that the desire for a series is more pressing for the marketing people than it is for the authors.

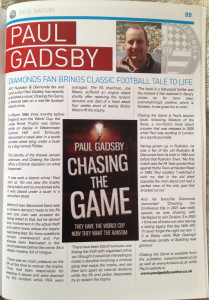

[Top]Chasing the Game appears in match programme

The matchday programme of my local football team, AFC Rushden & Diamonds, published a feature about Chasing the Game in its latest issue.

The matchday programme of my local football team, AFC Rushden & Diamonds, published a feature about Chasing the Game in its latest issue.

The in-depth feature included an interview with me that focused on the storyline and background of the novel as well as my history in supporting the Diamonds, which goes back to 1990 when the club was known as Rushden Town.

In June 2014 the AFC Rushden & Diamonds programme, edited by Stephanie Webb, won the Programme of the Year award for the entire United Counties League, which has 41 clubs over two divisions.

Chasing the Game of course has strong links with football, depicting a fictional version of the real-life theft of the Jules Rimet trophy in London ahead of the 1966 World Cup.

The crime thriller has received a raft of glowing reviews since its release, including from Britain’s biggest crime websites Crime Fiction Lover and Crime Time. For more details about the book and the true-life crime that influenced its narrative, please click here.

Chasing the Game can be ordered from the publisher Matador here, or on Amazon (paperback version) or ebook (just £1.99).

For more details about AFC Rushden & Diamonds, please click here.

[Top]The best on-screen portrayals of crime fiction characters

While reading through the Amazon reviews of my crime thriller Chasing the Game recently, I was struck by one comment in particular: “It would be interesting if the story could be dramatized for the 50th anniversary of the theft in 2016.”

The novel’s main character, Dale Blake, who plots the theft of the Jules Rimet Trophy in 1960s London, would certainly make a powerful and captivating on-screen presence, and it got me thinking about those actors who have really pulled off a performance that matched the momentous work of the author who created their character.

There have, of course, been many examples of on-screen portrayals of literary figures not working out (John Hannah’s version of Rebus just didn’t hit the mark) but let’s focus on the positives and run through some shining examples of compelling character acting that either lived up to – or even surpassed – our high expectations, having sat down to watch with the literary versions of these characters foremost in our minds.

The characters listed below are simply some choices I’ve made from my experiences of watching TV or film adaptations of my favourite books (and ones that I’ve managed to recall on the spare evening I’m writing this). I’ve thrown in a few unusual ones to catch the eye, but if you feel I’ve made a glaring omission or a ludicrous pick, tell me about it on Twitter – @PaulJGadsby – I’d love to chat about it with you.

Mark Strong as Harry Starks (The Long Firm)

Jake Arnott’s debut novel was a groundbreaking piece of fiction that rejuvenated the gritty British gangster genre, and charismatic nightclub owner and racketeer Harry Starks stole the show. When it came to the BBC’s four-part dramatization of the book, Mark Strong nailed the role to such a degree that it’s impossible to read the book now without imagining Strong’s face in every description of Starks and every line of his dialogue. Strong’s performance was magnetic, forceful, tender and utterly convincing, piercing into Stark’s complex and fascinating soul and capturing every single aspect of it.

Richard Attenborough as Pinkie Brown (Brighton Rock)

The 1947 film version of Graham Greene’s haunting classic is widely regarded as one of the finest ever cinematic expressions of British noir, and this was in no small part down to the skill Richard Attenborough applied to playing Pinkie, the story’s lead villain. A sadistic teenage gangster, a thrilling and terrifying embodiment of pure, irredeemable evil, Pinkie is one hell of a character to play and his relationship with young waitress Rose takes him on an emotional rollercoaster in the second half of the movie and Attenborough expertly maintains his immense control over the part throughout – resolute, chillingly sociopathic, and downright creepy wherever appropriate.

Gert Frobe as Auric Goldfinger

Okay, at some point I was going to squeeze a Bond villain into a list of crime fiction characters. Goldfinger was not only one of my favourite books from Ian Fleming’s series, it was also one of the best films from the franchise. German actor Gert Frobe captured the subtle gestures and nuances from Fleming’s alluring prose quite beautifully, and he just . . . looked like the guy you imagined in the book. Frobe was a strange casting choice as well – in that he couldn’t speak English – but that was nothing a bit of voice dubbing couldn’t fix. Frobe’s appearance and mannerisms matched the essence of the character, and for me he is the finest representation of a literary Bond villain we have seen, with Mads Mikkelsen’s portrayal of Le Chiffre in Casino Royale coming a close second.

Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes

Now we’re talking classic. Rathbone appeared as the cunning sleuth in 14 films between 1939-1946 and for me no one has quite matched him since. When I read the books, I imagine Rathbone’s face, Rathbone’s profile, Rathbone’s turn of phrase, Rathbone’s charm. The fact that Nigel Bruce’s stupendous depiction of Watson during those films has since blurred into the background perhaps says it all about the impact Rathbone brought to the lead role. With his deerstalker silhouette having reached iconic status, Rathbone will always be, for me, the quintessential Holmes.

Matt Damon as Tom Ripley (The Talented Mr Ripley)

A bit left-field this one but still worthy of extremely high praise. Patricia Highsmith was a glorious novelist and this is my favourite book of hers (just beating Strangers on a Train). There are so many angles to the character of Ripley, her darkly twisted young man who’s in Italy trying to escape his true self, that Damon really has his work cut out in order to slip into Ripley’s skin. Morally vacant, haunted, desperate, sad, lonely, evil, lost, gifted, tender – Damon masters them all in a powerhouse performance that’s as fantastically elegant as it is deeply unsettling. You just can’t look away from him on the screen. To me this is still Damon’s signature role despite the subsequent success of the Bourne franchise.

Ashley Judd as Joanna Eris (The Eye of the Beholder)

Marc Behm’s 1980 novel paints a vivid picture of this psychologically scarred character who’s no ordinary femme-fatale. The composed and striking Joanna employs her raw survival skills to hop from city to city, changing wigs and aliases as she preys on rich men before marrying and then killing them. A private investigator (played by Ewan McGregor in the film), absorbed by her life and fascinated by her backstory, follows her as she cuts a deadly swath from New York to San Francisco to Alaska with many scintillating stops in between. The killing is Joanna’s coping mechanism to get through life, but when she genuinely falls in love with a sophisticated but vulnerable wine merchant (who’s blind) and falls pregnant, tragedy strikes. Judd crawls into the heart and soul of Joanna, expressing her wild personality changes, her dark cunning and her crushing sense of abandonment and loss with such sincerity that we never judge her. We, like the PI who follows her, just want to watch and understand her.

Paddy Considine as Peter Hunter (Nineteen Eighty)

In this second instalment of the three-part Channel 4 serial depicting David Peace’s Red Riding Quartet, Peter Hunter is the lead detective in a disturbing fact-meets-fiction investigation to catch the Yorkshire Ripper. A Lancastrian called in to lead the paranoid and dejected Yorkshire CID team who’ve failed so far to catch their man, Hunter is up against it to get the officers who hate him on his side and the infamous serial killer behind bars. As the pressure mounts in a community gripped by fear and a police force riddled with corruption, Considine brings just the right amount of steel, anxiety and dismay to the role that Peace so poetically conveys in the book.

Ryan Gosling as Driver (Drive)

The lead role in this tale (James Sallis only ever referred to him as ‘Driver’ in his novel while in the film he was unnamed) is the archetypal example of the neo-noir hard-man male, a walking embodiment of the description ‘enigmatic’. The prose in the book is so startlingly sparse that we are captivated by this mysterious lead character and are desperate to know more about him. A Hollywood stuntman by day and underworld getaway driver by night, Driver is a weighty creation and Gosling does a mighty fine job of representing him faithfully on screen – his performance is poised, restrained, slick and brutal.

Anthony Hopkins as Hannibal Lecter (The Silence of the Lambs)

I guess the Academy Award says it all. Hopkins’ portrayal of Thomas Harris’ cannibalistic serial killer will never be forgotten. Clearly one of the most strikingly visual cinematic performances of all time, my favourite scene is how Hopkins appeared the first time we meet Hannibal as Clarice Starling approaches his cell. He’s not gripping the bars or slouched on his bed as he awaits his visitor; he’s standing bolt upright in the middle of the room, arms down by his sides, staring right at her. Chilling.

Humphrey Bogart as Philip Marlowe (The Big Sleep)

Another choice that perhaps picks itself. I think the strongest element to the 1946 film version is how the script is heavy with graceful dialogue rather than loaded with action – the characters are free to talk, in keeping with Raymond Chandler’s book. And when it comes to verbal tone and visual style, the cool Bogart earns the plaudits. His wry, humorous delivery, set amongst the beautiful black and white cinematography, just oozes noir, while his lusty on-screen chemistry with Lauren Bacall adds a dynamic, hearty charge to the narrative.

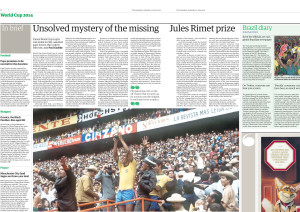

Chasing the Game featured in The Guardian

I’ve written an article published in The Guardian about the true-life crime that sparked the narrative behind my new novel Chasing the Game.