James Sallis – a tribute

This week marks the 70th birthday of one of the finest – and one of my favourite – contemporary writers, James Sallis.

This week marks the 70th birthday of one of the finest – and one of my favourite – contemporary writers, James Sallis.

A crime novelist, poet and musician, Sallis, younger brother of philosopher John Sallis, cultivated a reputation as an influential writer in the 1990s with his Lew Griffin series of books set in New Orleans. But it was his 2005 neo-noir thriller Drive that catapulted him to global literary acclaim and was adapted into a 2011 film of the same name, starring Ryan Gosling, Carey Mulligan and Christina Hendricks.

Sallis’ inimitable talent comes from a precious devotion to his craft. For many years he has combined his own work with teaching novel writing at Phoenix College in Arizona, while he also keeps his creative juices flowing by playing with his string band, Three-Legged Dog, his instruments of choice including the guitar, French horn, fiddle, mandolin, sitar and ukelele.

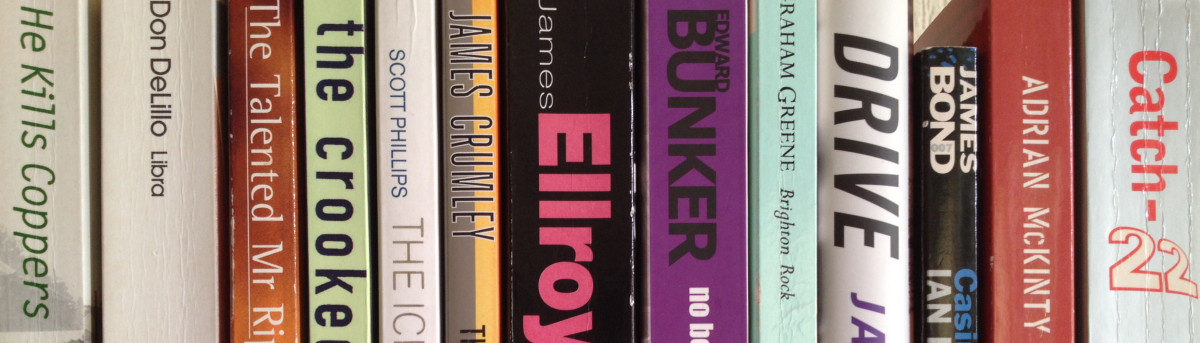

His work first came to my attention courtesy of the terrific support he has received from astute British indie publisher No Exit Press, who published his ex-con-turned-cop John Turner series as well as his Griffin books, a spy novel Death Will Have Your Eyes, along with Drive and the sequel to that classic, Driven.

Often referred to as ‘a crime writer’s crime writer’, Sallis is admired for his Hemingway-esque economy of language and the emotional depth of the fictional worlds he creates, amplified through the engaging philosophical outlook of many of his characters.

His back catalogue deserves to be swamped with praise, but it’s Drive that I’d like to focus on here. A gripping story of a young man abandoned from an early age and searching for an identity, he utilises his one passion – driving (the character is only ever referred to as ‘The Driver) to become a prolific Hollywood stunt driver by day and a wily getaway driver for the LA criminal underworld by night.

Paying homage to the successful style conventions of the noir genre, Sallis uses just 157 pages to pen a work dripping with existential minimalism, taut plotting, brutal hostility and sharp-witted dialogue, the actions of the intensely conflicted characters driven by the heart and a longing for their sense of place in the world.

One tool that Sallis maximises in a unique way is backstory. Interspersed at relevant points throughout the book, pieces of The Driver’s past are delicately presented to the reader in a way that skilfully hooks the reader in. Some of these passages aren’t as terse as you’d expect in a noir novel, but Sallis’ ability to always cut straight to the heart of the matter means you don’t feel like you’re being dragged away from the central narrative.

Although the book has its violent outbursts, none of this is graphic. The rich, flowing narrative, reminiscent of 50s noir but also laced with a 70s cult movie feel, keeps the pages turning. And despite the sharp detail offered in the flashbacks, The Driver remains a mysterious protagonist – like the book itself he is compelling, stark and beautiful.

‘I find Driver fascinating,’ Sallis once told GQ. ‘I wanted to make him this iconic, almost mythic American character . . . he accepts that the violence is who he is, what he does and he learns to embrace that.’

For me Drive remains James Sallis’ finest work; quaintly witty and utterly readable, it’s a literary masterpiece that elevates Sallis into the ranks of noir legends such as Jim Thompson, Graham Greene, James M Cain, Cormac McCarthy and even the Coen brothers.

As Sallis himself wrote in his essay, Standing by Death: ‘The deepest, most engaging and damaging moments of my life become notes, then pages and, finally, books. This is the purpose my life has taken. Maybe in the end it’s only that I want to leave a mark, something to show that I’ve been here.’