My new book Turbulence is published

Turbulence, my latest crime novel, has just been published by Fahrenheit Press.

The rippling effects of a violent crime have a devastating impact on six troubled and compelling characters in this multi-viewpoint tale of heartache and hope.

From the offenders and the innocent bystanders to the bank staff and the journalist trying to thread it all together, this book explores how one shocking incident and its turbulent aftermath can connect people from a variety of backgrounds, and how it shapes and haunts them all in different ways.

You can find out more about Turbulence and order the book here. It is available in paperback and ebook (Kindle and ePub). You can also order Turbulence on Amazon here.

[Top]Why ‘Graveyard Love’ is such a standout story

I’ve read many good books recently, but one is standing out from the rest of the pack by some distance — Scott Adlerberg’s Graveyard Love.

This intense, atmospheric noir has an innovative and daring premise that is developed with great poise and flair, marking the book out as a different beast to other dark thrillers out there.

Our narrator, unemployed 35-year-old Kurt Morgan, lives with his mother in her upstate New York home that overlooks a graveyard across the street. He becomes obsessed with an alluring red-haired woman who regularly visits the graveyard at dusk, watching her through a telescope in his room, wondering whose grave she visits like clockwork.

Kurt’s mother, meanwhile, is pressuring him to write her memoir, a project Kurt is disliking more and more with every passing day. Kurt starts following the red-haired woman and discovers she has a lover. A twisted game of paranoia develops between these four characters — Kurt, his mother, the graveyard woman, her lover — with each person pursuing their own twisted motivation at seemingly any cost. Kurt’s obsession turns out to be the strongest, and the most dangerous, as his resentment towards his mother — and his frustration at the cold encounters he has with the red-haired woman — intensifies.

Adlerberg cranks up the pace and tension here, propelling Kurt’s troubled mind into an irrational one as he falls deeper into the stalking vortex. We’re taken down a labyrinth of dark, claustrophobic, and unknown corridors as the author explores the far reaches of the human psyche. Forget the unreliable narrator, this is an insane one. We live with Kurt through every moment, from him approaching the lip of the whirlpool, to teetering over the edge, to falling right in. Disgusted and intrigued at his every move along the way.

The short length of the book (as taut novels tend to do) adds to the drama and imminent sense of danger, creating an unpredictable read amid a growing surge of menace as Kurt grows more unhinged.

Graveyard Love’s masterful breakdown of the warped mind of a main protagonist draws fair comparisons with Robert Bloch’s Psycho, Don DeLillo’s Libra, GBH by Ted Lewis, Marc Behm’s The Eye of the Beholder, and even the works of Alfred Hitchcock and Edgar Allan Poe.

I’d read one of Adlerberg’s books before, the zesty short story collection Dead Guy in the Bathtub, and this novel takes his writing to a new level. Dealing with voyeurism and obsession in such a riveting way, its uneasy, stealthy vibe creates a real sense of personality and represents one of the strongest manipulations of the first-person narrative I’ve come across.

[Top]Marking 100 years of Patricia Highsmith

Patricia Highsmith was born on this day 100 years ago. The American’s powerful and seductive crime fiction remains as relevant today as it ever has been.

Her debut novel, the psychological thriller Strangers on a Train, was released in 1950 to high praise – especially for her gripping, existential writing style.

Just a year later the book was adapted for the screen by Alfred Hitchcock, bringing Highsmith’s work to a larger audience. The riveting tale of how architect Guy Haines and the psychopathic Charles Bruno ‘exchange murders’ (Bruno offers to kill Guy’s unfaithful wife in return for Guy knocking off Bruno’s father) explored themes of identity and morality that Highsmith would become renowned for in the years that followed.

Her second novel would be just as dramatic, yet more personal. Writing under the pseudonym ‘Claire Morgan’, 1952’s The Price of Salt was a ground-breaking romantic lesbian novel that featured an unusual (for the time) happy ending. It was republished 38 years later as Carol, the eponymous main character being portrayed by Cate Blanchett in the 2015 film adaptation.

Highsmith’s work was gaining many high-profile plaudits, such as Truman Capote and Graham Greene, who labelled her ‘the poet of apprehension’. In 1955 Highsmith created one of the most iconic literary characters of all time in The Talented Mr Ripley, where the down-at-heel Tom Ripley senses a chance to start a new life by murdering a rich heir to a shipping company, who’s living a luxurious life in Italy, and stealing his identity. After Ripley lays on the charm and develops the courage to carry out the deed, he goes on to become a skilled con artist and serial killer in the later Ripley novels – Ripley Under Ground (1970), Ripley’s Game (1974), The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980) and Ripley Under Water (1991).

But despite the literary success, life wasn’t easy. Writing became a form of escapism and clarity for Highsmith, who suffered a troubled existence away from the typewriter. She endured several cycles of severe depression, developing a cynical, lonely and hostile persona – worsened by her dependency to alcohol. The intimate sexual relationships she formed, mostly with women, didn’t last long.

In 1982 she moved from New York, where she’d lived since she was six, to Switzerland, where she lived a remote existence until she died in February 1995, aged 74.

She left behind a body of work – 22 novels and nine short story collections – that few authors could match in quality or meaning. Highsmith was brave enough to explore her own instincts, ambitions and fears within her fiction, which in turn made it easy for readers to identify with her flawed characters and their tales of forbidden love, complex personal liaisons or starting over, all laced with fascinating psychological intrigue.

[Top]Revisiting ‘The Eye of the Beholder’

It is 40 years since the publication of Marc Behm’s hardboiled – yet stunningly surreal – PI novel, The Eye of the Beholder.

Later adapted into two films, including a 1999 version starring Ewan McGregor and Ashley Judd, this mesmerising tale from 1980 is an eclectic and experimental triumph – and for me one of the starkest, punchiest noir novels of all time.

The main character, known only as ‘The Eye’, is a field operative working for a corporate private investigation firm in Virginia. His latest assignment is to keep tabs on recent college graduate Paul Hugo, whose wealthy parents are concerned about a deviant young woman their son has gotten himself romantically involved with.

The Eye, long separated from his daughter who he only sees in sporadic illusions, is mentally unstable and finds himself fixated with the woman. He watches the young couple get hitched at the local city hall in a rushed ceremony and follows them on a drive to their honeymoon, becoming very much a voyeur now. When he watches the new bride calmly kill Paul that evening, dispose of the body and enjoy a peaceful night’s sleep, The Eye becomes infatuated.

Relinquishing his professional and legal obligations to report what he’s seen, he follows the woman to New York where, adopting a different alias and physical appearance, she befriends another wealthy male victim and kills him for the cash and cards he has on him. Worrying about the shallowness of the grave she’s buried him in amongst the trees, The Eye reburies the body deeper into the woods, fearful that if she gets caught, his days of watching her will be over.

He soon discovers that the woman has plenty of aliases and wigs as she criss-crosses the nation getting her hooks into one well-heeled victim after another – sometimes setting up a longer-term scheme by playing the bride for an inheritance payout, sometimes just helping herself to a quick score.

The Eye carefully watches her habits and does some research to find out her true identity, Joanna Eris, and uncovers a tragic past that explains her emotional detachment to the murders she carries out with such a callous flair. Picking up the trail again and living off his savings after the PI firm fires him, he sees Joanna marry an extremely affluent blind man. When her husband is killed in a car accident, The Eye watches the devastated Joanna scream in genuine, gut-wrenching pain and realises that this partner wasn’t one she intended to bump off.

Following her and watching her exploits – and sometimes helping to cover her tracks when her back is turned – becomes a way of life. Years, decades, pass. His twin obsessions of his lost daughter and the haunted, murderous Joanna dominate and warp his brain. Eventually, he works up the courage to approach Joanna and speak to her for the first time, thinking he can transform their bond into something more meaningful, more real. But the fates have another ending in mind.

Despite being a slender book, The Eye of the Beholder spans 30 years and covers nearly 100 killings. It’s an extraordinary work; brutal yet tender, rapid yet epic, and of course viciously bleak. A nihilistic descent into hell. Few books have explored themes of manic desire and sociopathic behaviour with such heartbreaking lyricism and relentless intensity.

Behm, born in New Jersey in 1925, became engrossed in French culture while serving there in the US army during the Second World War, and later moved to France permanently. He was a screenwriter as well as a novelist, penning the script for The Beatles’ movie Help! in 1965. He wrote seven novels between 1977-94 and died in Fort-Mahon-Plage in 2007. A gifted storyteller, The Eye of the Beholder is undoubtedly his finest work and deserves to be remembered for many years to come.

[Top]10 compelling settings in fiction

Setting is of course right up there with plot and characterisation when it comes to writing and enjoying a novel.

When a setting is depicted with great depth and detail, it becomes a character in itself within the book and brings the reading experience to life.

The useful thing about setting from an author’s perspective is that it can be extremely versatile. We could focus on a geographical location, such as a region (the wild crimson cliffs of Arizona), a city (the claustrophobic yet vibrant streets of London), or even narrow it down to a particular building or room (the Bates Motel in Psycho). We can also use setting to convey a certain time (the miners’ strike of the eighties, as David Peace did so effectively in GB84).

Whatever time or location is chosen, it is the responsibility of the writer to weave an array of authentic features into the work – while never distracting from the flow of the story – that will strike a chord with the reader and enrich the book.

Here are 10 examples of well-written settings that have magnified the impact of some of my favourite novels.

The Overlook Hotel, The Shining

Let’s start with a strikingly specific location. Stephen King’s classic tale starring winter caretaker Jack Torrance would be nowhere near as scary without the haunting depiction of the Overlook Hotel. Its isolated spot within the roaming Rocky Mountains of Colorado adds mystery and danger, while the building’s troubled history brings spiritualism into the mix. It all adds up to a deadly cocktail of fear, insanity and evil, sending Torrance’s cabin fever spinning out of control.

The Timberline Lodge in Mount Hood, Oregon, was used as the exterior for The Shining’s Overlook Hotel

The Peak District, Reservoir 13

A 13-year-old girl goes missing in a rural village in the Peaks, and the locals go searching for her in tandem with the police and diving squads. But the area’s web of deep reservoirs and substantial, boggy terrain complicates their quest. Author Jon McGregor delicately exposes the private squabbles and complex historical relationships within this tightknit community; the small becomes big. His abrupt sentences build tension and his sporadic use of local idioms, referencing the farming sector in particular, make every line feel real.

Brighton, Brighton Rock

Graham Greene’s landmark 1938 novel is a story of violence, contrition and love, but the backdrop to it all – the south-coast resort of Brighton – plays a powerful part in tying the themes together. The city’s slot machine rackets and thriving gangland culture, plus the winding streets and lanes and the open waves of the sea, add serious spice to this underworld thriller in the form of escapism and fatalism.

The Pacific Ocean, Dead Calm

Charles Williams takes us to the expansive open waters of the Mid-Pacific Ocean, where honeymooners John and Rae Ingram are looking for solitary bliss aboard their yacht. They rescue Hughie, a young man cast adrift in a lifeboat having escaped his sinking ship, and rather wish they hadn’t. Williams uses the eerie setting of lapping waves, vast isolation and distant horizons to explore the emotions of hope, fear and betrayal that the characters are experiencing.

221B Baker Street, Sherlock Homes

The home base of the most popular detective in the history of literature saw some serious action. With sidekick John Watson, who rooms with Holmes in many of the stories, and landlady Mrs Hudson in tow, there is always plenty of drama. Cases are introduced on the appearance of mysterious guests, ruminated on at length, and solved within these lodgings, with lashings of violence, gun pointing, violin playing and drug consumption (morphine and cocaine) along the way.

Munich Airport, by Greg Baxter

An American expat, his elderly father and an American consular official are trapped at fogbound Munich Airport, waiting for their flight which will also take the coffin carrying the former’s recently deceased sister home. As the bad weather delays their getaway, the book follows the three of them as they deal with being trapped in this awkward location for an undetermined period of time. Baxter is one of my favourite literary fiction writers and he steadily reveals profound character details with aplomb to make this a rich and philosophical read.

The Sun is God, by Adrian McKinty

Taking a break from his Sean Duffy series, this standalone book is set in 1906 on a remote island in the South Pacific, where a cult group of Europeans believe that worshiping the sun daily and eating only coconuts rewards them with eternal life. Former policeman Will Prior is sent there to solve a mysterious death, and experiences several dark and strange happenings amidst McKinty’s masterfully descriptive prose that vaults the island into an authentic bubble in the mind of the reader.

The Spy Who Loved Me, by Ian Fleming

Very different to the other Bond books, this tale is written from the first-person perspective of young French-Canadian woman Vivienne Michel. She is looking after an empty motel in the Adirondack Mountains, north east of New York, for a friend at the end of vacation season, but two nasty mobsters arrive and plan to have their way with her. Bond appears two-thirds of the way in looking for a room having had a flat tyre while passing. During a night of tensions, the mobsters set the motel alight in an attempt to kill Michel and Bond, and a dramatic gun battle and car chase ensues. Fleming is on top form, matching the isolation of the motel with Michel’s vulnerable mindset.

The Ice Harvest, by Scott Phillips

This quirky caper is set in Wichita, Kansas, right in the heart of America, as the snow descends on Christmas Eve. Rogue lawyer Charlie Arglist has close to a million stolen dollars on him and needs to leave, but his dodgy business partner, various angry family connections and local mobsters block his path. The guts of the city are laid bare here, from the grubby bars and seedy strip joints to cops on the take, all of the prose dripping with black humour that is pitched to perfection.

The Road, by Cormac McCarthy

Stories don’t come much more apocalyptic than this. A father and his young son walk through burned America for the coast, scavenging food and avoiding cut-throat vigilantes who will gleefully kill them for their provisions and clothes. The setting here is an all-encompassing one; the ravaged, globally-warmed landscape of a nation – but it feels intensely intimate when told through the terrifying scope of this desperate father-and-son duo.

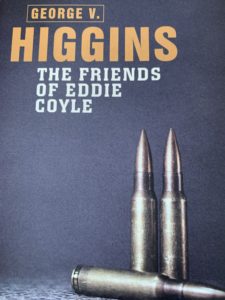

James Ellroy – always standing above the crowd

Born on this day in 1948, James Ellroy is possibly the most unique author that modern crime fiction has to offer.

Born on this day in 1948, James Ellroy is possibly the most unique author that modern crime fiction has to offer.

As successful as he is talented, Ellroy’s renowned staccato prose has attracted a deluge of fans and plaudits over the years. The American’s passion for bringing an array of crooked characters – many of them brutally so – to life on the page has seen him produce an exceptional list of books that have been gripping readers for the best part of four decades.

I first came across his work in the early 90s when I was getting into the crime genre. Looking for something at the other end of the spectrum to the cosy mysteries I’d been reading, I spotted on the bookshelves of my local indie a copy of Brown’s Requiem (his debut, published in 1981) and delved in. Boy, was I rewarded. The heavily-clipped writing style immediately appealed; darker and edgier than anything I’d read before, such an unsentimental tone to it, so authoritative, so knowing. He seemed to have a vice-like grip on both his characters’ motivations and how the world worked within a corrupt environment, making the story feel authentic to the core.

There was even better to come. Clandestine and Silent Terror (the latter was also published as Killer on the Road) continued exploiting the same themes of corruption and evil, before Ellroy catapulted to fame with what became known as the ‘LA Quartet’ (The Black Dahlia, The Big Nowhere, LA Confidential, White Jazz from 1987-92). I actually read these out of order first time around as I had difficulty tracking down The Big Nowhere in the pre-digital age, but they all work as cracking standalones.

Many of his works are intrinsically linked to real-life events, most notably the Black Dahlia being a high-profile murder case from 1947. Ellroy also mixed fact with fiction by using various political elements that led up to the JFK hit for his densely-plotted ‘Underworld Trilogy’ of American Tabloid, The Cold Six Thousand and Blood’s a Rover (published between 1995-2009).

The mean streets of post-WW2 Los Angeles have had a huge influence on his life and career, a period of course dripping with noir-esque imagery and nostalgia. The ruthless edge Ellroy brings to his work appears to come from his thirst to depict a variety of dishonest and damaged characters from all walks of life, including elite political circles. Put simply, no one writes about bad guys doing bad things as convincingly as Ellroy.

His tastes for dark scepticism and the callous things in life can also be connected to a traumatic incident in his childhood. When he was 10, his mother, Geneva Hilliker Ellroy, was raped and murdered. The case remains unsolved, despite Ellroy himself teaming up with a retired homicide detective to try and dig up new leads over an intense 15-month period in the 90s – an investigation that he chronicled in the non-fiction book, My Dark Places.

When discussing his own work, Ellroy has never been shy to place himself on the highest of pedestals, often using his media appearances to enforce his reputation as an overpowering presence as well as a hardboiled nihilist. He once said: ‘I am a master of fiction. I am also the greatest crime novelist who ever lived. I am to the crime novel in specific what Tolstoy is to the Russian novel and what Beethoven is to music.’

And also: ‘I’m the demon dog with the hog-log, the foul owl with the death growl, the white knight of the far right, and the slick trick with the donkey dick. I’m the author of 16 books, masterpieces all . . . these books will leave you reamed, steamed and dry-cleaned.’

At 6ft 3in tall, Ellroy naturally comes across as a larger-than-life character, and when he trots out some of the above quotes, he clearly stands out a mile from the more modest, understated approach adopted by many authors in public. But that’s the way it should be with inimitable stylists. His work is different to other crime writers, and it’s fitting that his personality is too. Literature needs a brazen force like James Ellroy.

[Top]What is the ideal length for a book?

Ah, this old chestnut. Discussion amongst writers, agents and publishers (but rarely readers, I find) often swings around to word count. How long should a book be? Has this changed over the years, and, if so, why?

Ah, this old chestnut. Discussion amongst writers, agents and publishers (but rarely readers, I find) often swings around to word count. How long should a book be? Has this changed over the years, and, if so, why?

Firstly, this will depend on the type of book (fiction/non-fiction/narrative non-fiction) as well as the genre. Each category has, over time, been pegged with certain word lengths determined by industry insiders attempting to gauge audience wishes and expectations. For the sake of this article, let’s talk about fiction books. There was a post recently doing the rounds on social media that I found interesting, where a New York-based literary agent advocated a ‘suggested word count chart’ published by Writer’s Digest.

In short, the suggestions ran as follows:

Below 70,000 – you’re too short

70-80K – it’s ok, may be short

80-90K – sweet spot

100-110K – probably ok, might be long

110k+ – unless you’re sci-fi or fantasy, you’re too long.

The post gained a fair bit of traction, with many stating that these word counts are too long and need refining. Chris Black, Senior Editor of indie publisher Fahrenheit 13, responded by saying: ‘Harsh. I’ve known plenty of greats in the 50-60K range. Take 40k off each category and it’s about right.’ Other comments such as ‘Love a nice tight story’ and ‘60-65k is gold’ were also commonplace.

I must say I sided with this view. Modern readers now have their book reading time seriously compromised by the constant consumption of the (entirely relevant and individually defined) information available on their mobile phone, as well as other bespoke entertainment options such as Netflix. Not to mention, in many cases, increased commuting times – and for those outside of London, that means driving. Few people have many chances to regularly sit down and read big chunks of a work at a time. To suggest below 70,000 is too short is crazy, especially in my preferred genres of crime/noir/mystery.

Some of my favourite contemporary writers such as Ken Bruen and Scott Phillips are often in the 60-70,000 range and sometimes below that. It’s also easy to forget that many classics didn’t subscribe to the ‘big is best’ theory. A Clockwork Orange was approximately 59,000 words long, while Ian Fleming’s debut Bond novel, Casino Royale, came in at 44k. Try these others for size: The Big Sleep (55k), The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (61k), The Great Gatsby (48k), Fight Club (49k), The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (47k).

I enjoy a sprawling James Ellroy as much as anyone, but if I want to get through 15-20 books a year to give myself a variable literary experience, I need plenty of reads where brevity was the author’s watchword.

There is too much emphasis within the publishing industry (I’m mainly looking at the big 5 here) on length, and conforming to the belief that readers associate a thick book with value for money. Are they really that bothered? The ones I speak to aren’t; they just want something they feel they’ll enjoy. A blurb with a strong hook is surely more powerful than bulkiness?

The same could be said for films. Want to plan the rest of your day around watching a new movie? Most of them are over two hours now, many towards or over three, as the companies want to justify the rising cinema ticket prices. I’m a big 90-minute fan. I want the story to be the experience, not the ‘cinematic experience’ to be taking up half my day with ads, trailers and a bloated main feature.

Going back to social media, I see many posts from writers (new and established) who are putting themselves under pressure by tracking their progress purely to word counts. ‘Phew, 5,000 words done today, target met!’

Yes it’s important to gather momentum when taking on such a sizeable project, but bashing out words for the sake of numbers can lead down a dangerous path. While the saying of ‘you can’t edit a blank page’ is obviously true, editing 5,000 crap words can take a whole lot longer than focusing on quality from the start. I’d rather spend a day writing 500 beautiful words than 5,000 churned-out ones.

Word counts are still important because they serve as a guide to how much of our investment, in terms of time, is required. However, don’t let this detract from more powerful factors such as organic pacing and storytelling. If you’re penning a novel, just focus on telling the story you want to tell in the first draft and consider those marketing-based word-count formulas later if you must. If you’re a reader, just continue enjoying the stories.

[Top]Olive Kitteridge is back

American author Elizabeth Strout is one of my favourite writers, and the imminent return of her most compelling character is a delightful prospect for any reader who enjoys smart, nuanced storytelling.

American author Elizabeth Strout is one of my favourite writers, and the imminent return of her most compelling character is a delightful prospect for any reader who enjoys smart, nuanced storytelling.

Olive, Again is being released next month, a follow-up to Strout’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2008 novel Olive Kitteridge, and I can’t wait to get my copy.

The PR blurb reads: ‘Olive, Again follows the blunt, contradictory yet deeply loveable Olive Kitteridge as she grows older, navigating the second half of her life as she comes to terms with the changes – sometimes welcome, sometimes not – in her own existence and in those around her.

‘Olive adjusts to her new life with her second husband, challenges her estranged son and his family to accept him, experiences loss and loneliness, witnesses the triumphs and heartbreaks of her friends and neighbours in the small coastal town of Crosby, Maine – and, finally, opens herself to new lessons about life.’

Rarely do characters come as multi-layered as Olive. Strout used all her creative expertise and deep understanding of human relationships to craft a powerful and quirky persona. Olive, an ill-tempered junior high school maths teacher who gives her husband short shrift at pretty much every opportunity, is brusque, flawed and fascinating in roughly equal measure.

Intellectually sharp yet lacking emotional intelligence, she is conflicted by, among many other things, feelings of guilt over an affair she has with a colleague at the school and severe frustration at her inability to show love and openness, particularly when in the company of her son.

Not one for social niceties, Olive’s bluntness and absence of self-awareness leads her down several rough and difficult paths. The character reached iconic status when portrayed by the mesmeric Frances McDormand in HBO’s 2014 TV series based on the book, the actress nailing the emotional complexity of Olive’s nature with exquisite compassion and discord.

It’s hard to believe that Olive Kitteridge was only Strout’s third published novel, considering the masterful poise and elegance of the writing style. The richness and authenticity of the title character is woven into a collection interrelated stories within the book, allowing the multiple perspectives to add wider context (a technique Strout echoes in the sublime Anything is Possible, released in 2017).

Olive, Again looks set to reaffirm Strout’s status as an extraordinarily gifted novelist whose place as one of the very best storytellers is already assured. Her vision and fully-rounded grasp of human behaviour – and her ability to translate that to the page – has given us an array of convincing characters – and they don’t come any more convincing than Olive Kitteridge.

“It turns out – I just wasn’t done with Olive,” Strout says. “It was like she kept poking me in the ribs, so I finally said, ‘Okay, okay’…”

[Top]Is The Chain worth all the hype?

A surge of excitement has been springing from literary circles in the build-up to this summer’s release of Adrian McKinty’s The Chain.

A surge of excitement has been springing from literary circles in the build-up to this summer’s release of Adrian McKinty’s The Chain.

Heavyweight authors such as Stephen King, Don Winslow and Dennis Lehane, together with a deluge of publishing insiders, critics and bloggers, have been waxing lyrical about the novel over the last few months having received their advanced reader copies – so many in fact that I was getting worried for McKinty that there wouldn’t be many readers left to actually buy the book following its release.

Fear not, for the buzz hasn’t stopped since its publication a couple of weeks ago and my purchase is another contribution to the royalty coffers. Readers of this site will know that I am a huge fan of McKinty, loving the rawness and nostalgia that comes from his Sean Duffy series and the brutal noir of his Michael Forsythe trilogy.

The Chain is a departure from his previous work, written more in the style of a commercial thriller to capture a wider scope of readers. The premise in a nutshell: Your phone rings. A stranger has kidnapped your child. To free them you must abduct someone else’s child. Your child will be released when your victim’s parents kidnap another child. If any of these things don’t happen, your child will be killed. You are now part of the chain.

A chilling start, and the best thing about the first half of The Chain is how McKinty’s trademark pace and tempo drives the story along. Rachel O’Neill, a mid-30s divorcee who is recovering from cancer, is the one who gets that dreaded phone call, informing her that her 13-year-old daughter Kylie has been kidnapped. Rachel acquires the support of ex-brother-in-law Pete, an Iraq war vet who has the weaponry and IT software knowledge to help her take on the people behind the chain.

Some reviewers have remarked about McKinty’s shift from crime novel to mainstream thriller here, but I’ve never been a fan of pigeon-holing books into genres that cover such vast material. The crossovers are inevitable. I’ve regarded all McKinty’s novels as ‘thrillers’, in that they are thrilling reads packed with thrilling action, and this work is no different.

It is heavily plot-driven of course, but it doesn’t come at the cost of losing any depth of characterisation. McKinty gives us short bursts of detail that bring the protagonists to life, that sharpen the edges. This is especially the case in the second half of the book that delves into the backstory of how the concept of the chain was formed and the people behind it. Although I won’t give much away for fear of spoilers, it is these darker elements to the story that really give the book that punchy, visceral McKinty feel.

The plot is reliant on several parents from a non-criminal background taking on, in turn, a string of unfamiliar and life-threatening tasks. Scouting and prepping a suitable hideaway, planning and successfully carrying out the ruthless kidnapping of a child, becoming proficient in the use of firearms, hiding evidence of their identities in all communications, covering their tracks physically and digitally, convincingly threatening the next parent in the chain, etc. In the hands of some authors, this might come across as slightly implausible, but McKinty is a safe pair of hands. His years of quality writing experience allow him to paint a vivid picture of what motivates his characters, in this case demonstrating that the besieged parents, suffering from the gut-wrenching pain of having their child taken from them, are driven by that very despair – and the guilt they will have to live with if they don’t pull this off – to stoop to whatever level is necessary to get their child back. A primeval force takes over.

As Rachel herself surmises: ‘Even an imbecile knows you don’t get between a grizzly-bear mama and her cub’

The Chain is a breath-taking read worthy of the hype surrounding it and no writer deserves the success more than McKinty (Paramount have already bought the film rights in a seven-figure deal). In recent interviews McKinty has revealed that – despite the critical acclaim and awards that his backlist has received – he was on the verge of quitting writing due to a lack of monetary return. This came as a surprise to me as I was under the impression that his standing as one of the top British crime writers meant he was doing pretty well earnings wise.

It says a lot about the state of the current publishing industry that such a talented and relatively high-profile author, whose books received coverage in the national press, was struggling to earn a living from the trade. No wonder he wanted to go down the route of producing a more commercially-orientated standalone – and thankfully it’s a belter.

[Top]Some of the hottest new reads out there right now

Aside from the day job and promoting my noir thriller Back Door to Hell in recent months, I’ve still been finding time – as always – to read some riveting books.

Aside from the day job and promoting my noir thriller Back Door to Hell in recent months, I’ve still been finding time – as always – to read some riveting books.

So to give you a flavour of what I’d recommend at the cutting edge of contemporary crime fiction, below are some reviews I’ve posted for some of my favourite reads of 2019 so far…

Last Year’s Man, by Paul D. Brazill

I’ve always been fascinated by the ageing gangster/hitman theme and this slick and stylish noir thriller from Paul D. Brazill is a barnstorming success.

Tommy Bennett, feeling heat from the London law after a botched job, returns to his native north east (a nice nod to Get Carter) to lay low and regroup. But reconnecting with old underground acquaintances and family members is no easy thing, nor is dealing with a weakening bladder and increasing medication routines, and Tommy needs to show all his grit and resourcefulness to steer clear of dangerous old ghosts haunting him.

Structured within an easily digestible novella length, this is a breezy tale filled with Brazill’s familiar sharp, clipped dialogue. There are plenty of laugh-out-loud one-liners, while the cultural references are relevant and the violence is vivid. The free-flowing narrative makes this a really enjoyable read and a standout addition to this author’s extremely credible back catalogue.

Dread: The Art of Serial Killing, by Mark Ramsden

This smart, sharply observed thriller is a thoroughly entertaining and rewarding read.

Few main protagonists are as entrancing and depraved as the Dickens-obsessed Madden, a spy and a serial killer who’s spinning more than a few plates as he infiltrates a right-wing nationalist group.

Aside from the charismatic and twisted hero/anti-hero, the prose style is a real highlight to this book. Shifting in tone from despair to graphic with a slick rhythm and a healthy dose of perfectly pitched dark humour throughout, the author is effortlessly in control of where he’s steering you.

The tempo and style reminded me of the brutal yet eloquent noir of Matthew Stokoe in places. This is a read that you won’t forget in a hurry – highly recommended.

Townies: And Other Stories of Southern Mischief, by Eryk Pruitt

I love short story collections and I’ve come across some of Eryk Pruitt’s writing in a few crime anthologies, but this was my first experience of a whole book of his work.

His range is impressive – in terms of subject matter, characters and setting – and there’s something here for every fiction fan, from a humorous take on a vengeful tale about profiting via fantasy football to a cruel battle over a lawn mowing route.

The dialogue in every story is convincing and the themes explored – whether it’s violence, the threat of violence, desperation or redemption – are delivered with care an aplomb. Lots of showing not telling, lots of brutality and second guessing, this author has a lot of control over his writing and the stories had me entertained and, in some cases, spellbound.

Dead is Beautiful, by Jo Perry

The Charlie and Rose series has captured the hearts and imagination of many readers, and with this latest instalment it’s easy to see why.

Charlie and his ghostly canine companion Rose, both dead and existing in a surreal afterlife, return to LA in this new mystery crammed with hardened prose, dry humour, and of course dark, dark noir.

A mature tree is felled illegally, throwing the two protagonists into an investigation that leads to a murder and into the path of Charlie’s brother, who’s in danger and needs help. Charlie, who never got on with his sibling, is trapped in a state of melancholy for much of this tale and needs the good-natured and perceptive Rose by his side more than ever if he’s going to power through.

Exploring the city’s homelessness as well as its luxury mansions, this book has great range of setting and character. The profound tone of the story is complemented by the brusque writing style and existential backdrop, all played out with a shrewd, ironic edge.

Fahrenheit Press deserve great praise for putting their faith in this brave and accomplished series. ‘The coolest collection of hardboiled and experimental crime fiction on the planet’ is the blurb of imprint Fahrenheit 13 – on this evidence, that claim is being fulfilled in spades.

Death of an Angel, by Derek Farrell

Danny Bird’s fourth adventure, this book is woven with a delightfully smooth and engaging writing style that really hooks you in from the start.

The stakes are high for the main protagonist, a bar manager/amateur sleuth, as he attempts to solve a multi-layered mystery that is intricately plotted and laced with polished humour. Danny’s exploits see him exposed to a wide range of characters and settings, up against high-powered corruption as well as domestic and personal strife.

The prose has a gorgeous, warm flow to it that particularly appealed to me, while the story is skilfully structured as it builds to a fitting crescendo.

Like all good series books, Death of an Angel also works as a standalone, with the various twists and turns – all driven from, or towards, the heart of the main character – unravelled with masterful elegance.

Broken Dreams, by Nick Quantrill

Down-at-heel PI Joe Geraghty, scraping a living in the northern, isolated city of Hull, is hired by a local businessman to investigate a staff member’s unexplained absenteeism. The case soon leads Geraghty into the heart of a murder investigation that carries links to Frank Salford, a key businessman central to the city’s regeneration scheme who is also a ruthless gangland boss.

The pace of this book is strong from the start and the drama heightens nicely as the story unfolds and the stakes rise. Geraghty is a very well-drawn character, the naturalness of his mannerisms, behaviour, outlook and dialogue really flesh out the believability factor in him. So many authors try to make their characters appear real by homing in on their ‘normal’ qualities to make them likeable and it can feel too contrived, but everything about Geraghty – the good and the bad – comes across as authentic in an effortless way.

But there’s another major character that deserves a mention here – Hull itself. Reading the book from the perspective of someone who has never been there but has felt enriched by visiting many northern cities, including living in one for four years, I felt this was a real bonus in Broken Dreams. Getting to know the many parts of Hull, from its past as a fishing fortress to its modern-day cultural renaissance, and feeling its gritty core and warm soul contributes significantly to the success of this urban tour-de-force.

[Top]“Thrills, spills, emotional depth” – Back Door to Hell continues to impress readers

The positive reviews for my noir crime thriller Back Door to Hell keep rolling in.

The positive reviews for my noir crime thriller Back Door to Hell keep rolling in.

Highly revered author and jazz musician Mark Ramsden, writer of eight novels including The Sacred Blood and Dread – The Art of Serial Killing, gave Back Door to Hell a full five stars in his review on Goodreads.

He wrote: ‘Thrills, spills, emotional depth. Back Door to Hell’s fugitive couple have rightly drawn some comparisons with True Romance . . . this is as exciting as a Quentin Tarantino script.’

‘Events unfold realistically rather than for effect or as an homage. There’s accurate social commentary, good sense of place. This does not take place in an alternative comic book universe: Back Door to Hell is real,’ he added.

‘Very soon after starting you have to know what happens next. Which isn’t what you thought it would be yet makes perfect sense. Highly recommended.’

Another review written by US-based crime fiction aficionado Nicola Parry said: ‘This is a great read.’

‘Paul Gadsby reeled me into this story with a relaxed writing tone that kind of left me feeling like I was an onlooker in it, watching the crime play out . . . I dare you not to be rooting for this crime duo as they trip around England, trying to avoid the consequences of their actions.’

‘I don’t know why, but all the way through this book, I could hear Pulp’s ‘Common People’ playing in my head.’

‘Overall, it’s brilliant, harrowing, and poignant. It’ll definitely leave you wanting more.’

Another reviewer on Amazon wrote: ‘Back Door to Hell takes us on a journey from South London to The Lakes, The North Sea Coast and back again at breakneck speed in the company of two engaging young anti-heroes.

‘If George Pelecanos had come from this side of the Atlantic, his prose would sound like this … Gadsby’s attention to detail and character development within a crisply executed story cannot be faulted.’

Further feedback for Back Door to Hell can be found here and here, while more information about the novel is available here.

Back Door to Hell is available in both paperback and ebook formats from Amazon or direct from publisher Fahrenheit Press.

[Top]“A very British True Romance” – further praise for Back Door to Hell

More rave reviews have been flooding in for my noir thriller Back Door to Hell.

More rave reviews have been flooding in for my noir thriller Back Door to Hell.

After an initial burst of positive feedback from critics and fans on publication by Fahrenheit Press, the novel has received a further batch of excellent reviews from all corners of the globe.

Critically-acclaimed crime author Aidan Thorn called the book ‘A very British True Romance’ in his review posted on the Fahrenheit website.

‘So much to enjoy here,’ he added. ‘The relationship between the two young thieves, reminiscent of Clarence and Alabama in True Romance, the depth to the often neglected bad guy, Crawford, with a glimpse into his home life. All of that is wrapped in a cat and mouse that despite the depth remains tense and interesting.’

Over on AustCrime, a website based in Australia that focuses on Australasian crime fiction as well as books from around the world, Gordon Duncan wrote: ‘Back Door To Hell really stands out.’

‘The story of boy meets girl, boy is convinced by the girl to take part in a robbery, all does not go to plan and boy and girl go on the run seems on the surface to be a familiar one, there are however many more layers to this excellent noir novel.’

‘Nate and Jen . . . not only need to trust each other, they must also decide who else to trust if they are to survive. I highly recommend reading Back Door To Hell to find out if they do.’

On The Irresponsible Reader blog, based in Idaho, USA, HC Newton said of the novel: ‘This is a fast-moving book, and the pages just melt away . . . It’ll draw you in and keep you riveted through all the twists and turns. And each time you start to think you know what’s going to happen, Gadsby will tell you that you’re wrong. And then he’ll throw a curveball at you.’

‘This is a treat folks, you’d do well to indulge.’

[Top]#Fahrenbruary shines a light on indie publishing

A month-long, blogger-led campaign has celebrated the works of Fahrenheit Press and highlighted the value and impact that passionate readers bring to the success of independent publishing.

A month-long, blogger-led campaign has celebrated the works of Fahrenheit Press and highlighted the value and impact that passionate readers bring to the success of independent publishing.

The #Fahrenbruary online festival, a spontaneous brainchild of book bloggers @laughinggravy71 and @thatmattkeyes, ran throughout February and encouraged fellow bloggers as well as authors and crime fiction fans of any description to get involved by reading a Fahrenheit book and posting a review, whether that be on their own site or on Fahrenheit, Amazon, Goodreads etc.

As well as spreading the word about all things Fahrenheit and celebrating the company’s glorious and daring output, the campaign achieved a wider scope of promoting the efforts and importance of indie publishers in general.

I contributed by writing a guest post on the Laughing Gravy blog titled ‘Couples on the run that inspired Back Door to Hell’ which ran through some compelling and famous books that I used as inspiration for the plot behind my noir novel Back Door to Hell.

I discussed further details about the book and also talked about my writing background and my thoughts on the independent publishing sector in a Q&A article on the Laughing Gravy site.

I also published a few reviews of some of my own favourite Fahrenheit books – Broken Dreams by Nick Quantrill, Burke’s Last Witness by CJ Dunford and When the Music’s Over by Aidan Thorn.

[Top]