10 of the best book sequels

Writing a follow-up to a big hit can be a huge challenge and one that few authors really pull off.

Writing a follow-up to a big hit can be a huge challenge and one that few authors really pull off.

But here are 10 fine examples where the sequel does full justice – or even enhances – a fantastic crime novel that caught the imagination. Huge success stories in their own right, you could say…

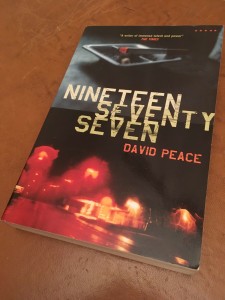

Nineteen Seventy-Seven

David Peace’s evocative debut novel, Nineteen Seventy-Four, made a big impact on the British literary crime scene and his follow-up, Nineteen Seventy-Seven, gave us more of his vivid depictions of a corrupt Yorkshire police force and bleak, northern communities terrified and bewildered by the Yorkshire Ripper murders. This sequel was a standout slice of what turned out to be a four-part series labelled The Red Riding Quartet, featuring several recurring and connecting characters, the flaws and fights of all them beautifully described in relentless, unyielding fashion.

The Big Nowhere

If The Black Dahlia turned James Ellroy into one of the hottest crime writers around in 1987, his sequel to it a year later, The Big Nowhere, elevated his status to one of the most powerful literary voices in crime fiction history. An engrossing tale of disgraced detectives, alcoholic anti-heroes, Hollywood Communists and a brutal sex murderer set against the backdrop of a post-war Los Angeles smeared with greed, deception and paranoia, this is a disturbing masterpiece.

Driven

I describe James Sallis’ scintillating short novel Drive elsewhere on this site as ‘a work dripping with existential minimalism, taut plotting, brutal hostility and sharp-witted dialogue’ and the book’s main character, the ‘Driver’, a Hollywood stunt driver by day and a wily getaway wheelman for the LA criminal underworld by night, returns in Driven. This is a classic sequel that, set seven years later, digs deeper into the instinctive make-up of this cryptic hero while taking the reader on a glorious ride. Modern noir at its finest.

The Dead Yard

Adrian McKinty’s stunning novel Dead I Well May Be introduced us to Belfast-born Michael Forsythe, an ambitious and resourceful lackey for a New York mob who, after being double-crossed big time, grows up fast into a cool and cunning killer. Five years later in The Dead Yard Forsythe is infiltrating an IRA sleeper cell in New England, living by his wits, falling in love and killing time and time again in order to stay alive. Few thrillers, if any, are written with such convincing action sequences as this rip-roaring read.

Ripley Under Ground

Patricia Highsmith’s wonderful follow-up to The Talented Mr Ripley is a fantastic psychological thriller and also a fine example of re-visiting a defining character in a very different setting to how they were introduced. The days of posing as Dickie Greenleaf behind him, Ripley is now living with a stylish – and of course wealthy – wife in rural France and running an art forgery scam, but after being exposed faces an enthralling battle to maintain his lavish Continental lifestyle and his freedom.

Farewell, My Lovely

Raymond Chandler brings back LA private eye Philip Marlowe in this 1940 sequel to The Big Sleep. This glorious book oozes style with an array of dazzling dialogue as Marlowe gets dragged into a murder that leads to a gang of jewel thieves, city corruption and a whole lot more murders. No wonder it was adapted for the screen three times.

Live and Let Die

This second James Bond book is a classic that builds on the momentum of Ian Fleming’s debut hit, Casino Royale. A lightning quick plot taking in striking locations such as Harlem, Florida and Jamaica together with some sharp characterisation allows readers to get deeper under the skin of this fascinating secret agent. The tone of this book, released in 1954, is heavier than the first as Fleming does a terrific job of placing Bond at the heart of these formative Cold War years, as well as in the middle of tense Anglo-American relations.

McKenzie’s Friend

Irish writer Philip Davison introduced reclusive MI5 understrapper Harry Fielding in The Crooked Man in 1998, and three years later brought him back in McKenzie’s Friend, a delightful novel exploring Harry’s complex relationship with his arrogant employers, his dementia-stricken father and his old mate Alfie, a bent cop who’s about to drag Harry deep into the mire.

Live by Night

Dennis Lehane’s epic follow-on to The Given Day, this is heavyweight crime fiction at its hard-hitting best. Joe Coughlin turns from small-time thief to big-time outlaw in 1920s Boston in this sprawling journey of violence, betrayal, love and pain. One of those rare examples of a long book that’s quick to read.

Donkey Punch

Cal Innes, our damaged hero from Saturday’s Child, has left his PI business behind to take on a caretaker’s job at a Manchester boxing club in this cross-Atlantic classic by Ray Banks. Shepherding/babysitting promising amateur pugilist Liam to a tournament in Los Angeles, Innes gets more than he bargained for when he discovers the competition is fixed by the kind of sinister underworld types he thought he’d left behind in the gritty north.

Honourable mentions must also go to the following sequels – some outside of my treasured crime fiction genre – that nearly broke into the top 10 (and funnily enough make a top 20):

Closing Time, Joseph Heller’s follow-up to Catch 22

The Crossing, Cormac McCarthy’s sequel to All the Pretty Horses

Imperial Bedrooms, the follow-up to American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

The Killing of the Tinkers, Ken Bruen’s sequel to The Guards

The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole, Sue Townsend’s follow-up to the best-selling The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole

The Sicilian, regarded as Mario Puzo’s literary sequel to The Godfather

Porno, Irvine Welsh brings Renton and Co back 10 years after Trainspotting

Go Set a Watchman, Harper Lee’s sequel – or earlier draft, depending on your take – of To Kill a Mockingbird

The Lost World, Michael Crichton’s follow-up to Jurassic Park

Bring up the Bodies, Hilary Mantel’s sequel to Wolf Hall.

Standalone books v series

As you can see from my influences page, many of my favourite books are standalone novels, but there are also some works that form part of a series.

Many a literary agent/editor/publisher will tell you that, particularly with crime fiction, long-running serials sell much better than standalones. Beginner writers are continually told by industry insiders that, if they want to break into the market, they stand a much better chance if they pen a manuscript ensuring the main character will return (preferably on many occasions) rather than fashion a one-off tale.

But why is this? Why are the series more appealing to readers and therefore more successful in the marketplace? Here are my thoughts, analysing the pros and cons of both standalones and series.

Standalones – the pros

By their very nature, standalones generally depict a very passionate story. The author has composed the tale based on a burning theme they wanted to pursue, a poignant story they wanted to unravel and a certain message they wanted to transmit to the reader. And they have been free to express that story in any way they see fit, tying up any loose ends (to an ultimate conclusion) if they wish, exploring any theme or location to the very limit, knowing they or their characters will never go down this road again. The shackles aren’t as much off; they were never on in the first place.

Authors can also lead their main protagonist down any dark alley they want to, even if the outcome proves fatal. The reader is on edge because they know that the character they’ve related to and connected with faces any degree of peril. The writer is doing it their way; they are pulling all the strings because they are under no pressure to sustain any part of the story or a character for a future instalment.

The authors are writing with their hearts, holding nothing back. Fire is in the belly as well as the fingertips as they unleash their saga. Whenever a media outlet releases a list of the greatest (or most popular) novels of all time, standalones are always there standing proud. For Whom the Bell Tolls, Catch 22, David Copperfield, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Day of the Jackal, The Killer Inside Me, The Great Gatsby, American Psycho, Scoop, Disgrace, Libra, The Road, No Beast so Fierce and many, many more. Works that carry a central emotive core and bare the author’s soul; unbridled creations and unique artefacts.

Standalones – the cons

Imagine if Ian Fleming, having written his heart out on his debut novel Casino Royale, had left James Bond at that point and moved on to another project, 007 confined to history in 1953. Standalone books provide us with great high-stakes tales but there’s the downside that stopping at one story prevents further development of a fascinating character, denying us the prospect of enjoying this protagonist taking on more challenges and allowing us to bond with them further. There’s no doubt that the huge cultural impact certain recurring characters have had on the world (Bond, Sherlock Holmes, Philip Marlowe et al) has done wonders for crime fiction and duly rewarded their authors with much deserved adulation.

Another point to consider here is that sometimes a standalone can be too long (Don DeLillo’s Underworld breached into this territory, as did Against the Day by Thomas Pynchon), possibly to the extent that you feel the author probably considered splitting it into a mini-series somewhere along the way but stuck with it anyway. And sometimes the total freedom an author enjoys with a standalone can lead to self-indulgence and a story/theme that winds out of control, but in a trade that depends on huge reserves of creativity and bravery, that’s often a small price to pay.

Series – the pros

Within the context of a series, particularly a long-running one, absorbing characters can be further enriched so they become legends, both literary and cinematic. There is plenty of room in standalones to develop and focus on characterisation (as there is setting and plot) of course, but with a series we just get to spend more time with our heroes, or at least people we’re fascinated by and have formed a connection with.

Another good thing about serials, especially in crime fiction, is that the cream of writing talent often rises to the top; series formats have allowed some magnificent writers to forge thoroughly deserved successful careers. Not many publishers dish out multi-book deals to poor writers. The likes of Patricia Highsmith (Thomas Ripley), Ian Rankin (Rebus), Mark Billingham (Thorne), Ken Bruen (Jack Taylor), James Sallis (Lew Griffin & The Driver), Adrian McKinty (Sean Duffy & Michael Forsythe), James Lee Burke (Dave Robicheaux), James Crumley (Milo Milodragovitch & C.W. Sughrue) and Ray Banks (Callum Innes) have all developed as writers over the course of sticking with their returning characters, the pressures of meeting their regular instalments perhaps forcing them to harness their craft in a quicker – and ultimately more confident way – than they otherwise would have done.

Serials also offer authors the opportunity to write a smartly conceived mini-series based mainly on theme rather than one principal character. With these each book is often significantly different in terms of timeframe or minor characters becoming major ones in the next book and vice versa. David Peace’s Red Riding quartet would fall into this category, a wonderful series that wouldn’t have been anywhere near as powerful as a standalone, nor a long-running series. James Ellroy’s LA quartet and Underworld trilogy also spring to mind here, as do Scott Phillips’s The Ice Harvest and The Walkaway, the narratives of those two connected works separated by 10 years.

Series novels also tend to get talked about more in social circles (so I’ve noticed anyway), allowing more opportunities for readers to share their experiences. An extensive, consistent body of work seems to bring people together more than standalones appear able to, and anything that gets people talking about reading, whether it’s at home, work, the beach or on social media, is a positive thing.

Series – the cons

The downside of an author under pressure to publish an annual instalment of a long-running series is of course the danger that they end up just churning them out. Just as their main character may have helped that author achieve fame, the process can also push them over the edge, their creative forces crashing and burning. Pumping out a novel a year to meet marketplace pressure can be a trap to penning prose unworthy of the writer and their initial ambitions, and that’s a real shame.

There’s also the danger of too many new writers feeling they have to launch their career with a main character that has ‘plenty of legs’, which all too often leads to the creation of a cliché-ridden detective we’ve all read enough of. You know the type; divorced, has a troubled relationship with his teenage son/daughter who’s growing up too fast, puts his work before his health and lifestyle, he’s the only one who despises corporate suits and bureaucracy, he unwinds in the winter evenings by listening to music anyone under 35 would scoff at, with a stiff drink in his hand. And the evil activities of each particular rival he encounters eventually results in the duo facing off in a duel, where the arrogance of the criminal leads to victory for the humble hero.

The readers lose out big time here. Not only can the returning character lose their appeal, but the plot can also lose its punch. Let’s face it, as the stakes rise in the final third we always know the main character will get out of this latest scrape relatively unscathed because they’ll be back for another adventure next year.

An example of an author who made his name with a solid series but broke free of the format to express himself in standalones is Dennis Lehane. After five instalments of blue collar detective duo Patrick Kenzie and Angela Gennaro, he pulled himself away to write Mystic River (later adapted into a Hollywood blockbuster) and then Shutter Island (ditto), two superb one-off thrillers that were both critically acclaimed and commercially successful.

Series are obviously easier to market. The industry loves them, often to the extent that a new release is promoted as a series right from the off. The first time I saw publicity for Malcolm Mackay’s debut novel The Necessary Death of Lewis Winter, it was labelled as the first instalment of ‘the Glasgow trilogy’. Almost as if his agent pitched the debut manuscript to a publisher who said “Forget it – unless your guy’s got two more up his sleeve, then I can call it a trilogy and I’ll have something to sell”.

David Peace’s ‘Tokyo trilogy’ was marketed as such on the release of the first instalment in 2007. After releasing the second in 2009, Peace drifted away from the concept and wrote Red or Dead, his standalone football novel about the late Bill Shankly. At the time of writing (September 2014) there’s still no sign of the final part of the Tokyo trilogy. Perhaps a sign that the desire for a series is more pressing for the marketing people than it is for the authors.

[Top]