10 compelling settings in fiction

Setting is of course right up there with plot and characterisation when it comes to writing and enjoying a novel.

When a setting is depicted with great depth and detail, it becomes a character in itself within the book and brings the reading experience to life.

The useful thing about setting from an author’s perspective is that it can be extremely versatile. We could focus on a geographical location, such as a region (the wild crimson cliffs of Arizona), a city (the claustrophobic yet vibrant streets of London), or even narrow it down to a particular building or room (the Bates Motel in Psycho). We can also use setting to convey a certain time (the miners’ strike of the eighties, as David Peace did so effectively in GB84).

Whatever time or location is chosen, it is the responsibility of the writer to weave an array of authentic features into the work – while never distracting from the flow of the story – that will strike a chord with the reader and enrich the book.

Here are 10 examples of well-written settings that have magnified the impact of some of my favourite novels.

The Overlook Hotel, The Shining

Let’s start with a strikingly specific location. Stephen King’s classic tale starring winter caretaker Jack Torrance would be nowhere near as scary without the haunting depiction of the Overlook Hotel. Its isolated spot within the roaming Rocky Mountains of Colorado adds mystery and danger, while the building’s troubled history brings spiritualism into the mix. It all adds up to a deadly cocktail of fear, insanity and evil, sending Torrance’s cabin fever spinning out of control.

The Timberline Lodge in Mount Hood, Oregon, was used as the exterior for The Shining’s Overlook Hotel

The Peak District, Reservoir 13

A 13-year-old girl goes missing in a rural village in the Peaks, and the locals go searching for her in tandem with the police and diving squads. But the area’s web of deep reservoirs and substantial, boggy terrain complicates their quest. Author Jon McGregor delicately exposes the private squabbles and complex historical relationships within this tightknit community; the small becomes big. His abrupt sentences build tension and his sporadic use of local idioms, referencing the farming sector in particular, make every line feel real.

Brighton, Brighton Rock

Graham Greene’s landmark 1938 novel is a story of violence, contrition and love, but the backdrop to it all – the south-coast resort of Brighton – plays a powerful part in tying the themes together. The city’s slot machine rackets and thriving gangland culture, plus the winding streets and lanes and the open waves of the sea, add serious spice to this underworld thriller in the form of escapism and fatalism.

The Pacific Ocean, Dead Calm

Charles Williams takes us to the expansive open waters of the Mid-Pacific Ocean, where honeymooners John and Rae Ingram are looking for solitary bliss aboard their yacht. They rescue Hughie, a young man cast adrift in a lifeboat having escaped his sinking ship, and rather wish they hadn’t. Williams uses the eerie setting of lapping waves, vast isolation and distant horizons to explore the emotions of hope, fear and betrayal that the characters are experiencing.

221B Baker Street, Sherlock Homes

The home base of the most popular detective in the history of literature saw some serious action. With sidekick John Watson, who rooms with Holmes in many of the stories, and landlady Mrs Hudson in tow, there is always plenty of drama. Cases are introduced on the appearance of mysterious guests, ruminated on at length, and solved within these lodgings, with lashings of violence, gun pointing, violin playing and drug consumption (morphine and cocaine) along the way.

Munich Airport, by Greg Baxter

An American expat, his elderly father and an American consular official are trapped at fogbound Munich Airport, waiting for their flight which will also take the coffin carrying the former’s recently deceased sister home. As the bad weather delays their getaway, the book follows the three of them as they deal with being trapped in this awkward location for an undetermined period of time. Baxter is one of my favourite literary fiction writers and he steadily reveals profound character details with aplomb to make this a rich and philosophical read.

The Sun is God, by Adrian McKinty

Taking a break from his Sean Duffy series, this standalone book is set in 1906 on a remote island in the South Pacific, where a cult group of Europeans believe that worshiping the sun daily and eating only coconuts rewards them with eternal life. Former policeman Will Prior is sent there to solve a mysterious death, and experiences several dark and strange happenings amidst McKinty’s masterfully descriptive prose that vaults the island into an authentic bubble in the mind of the reader.

The Spy Who Loved Me, by Ian Fleming

Very different to the other Bond books, this tale is written from the first-person perspective of young French-Canadian woman Vivienne Michel. She is looking after an empty motel in the Adirondack Mountains, north east of New York, for a friend at the end of vacation season, but two nasty mobsters arrive and plan to have their way with her. Bond appears two-thirds of the way in looking for a room having had a flat tyre while passing. During a night of tensions, the mobsters set the motel alight in an attempt to kill Michel and Bond, and a dramatic gun battle and car chase ensues. Fleming is on top form, matching the isolation of the motel with Michel’s vulnerable mindset.

The Ice Harvest, by Scott Phillips

This quirky caper is set in Wichita, Kansas, right in the heart of America, as the snow descends on Christmas Eve. Rogue lawyer Charlie Arglist has close to a million stolen dollars on him and needs to leave, but his dodgy business partner, various angry family connections and local mobsters block his path. The guts of the city are laid bare here, from the grubby bars and seedy strip joints to cops on the take, all of the prose dripping with black humour that is pitched to perfection.

The Road, by Cormac McCarthy

Stories don’t come much more apocalyptic than this. A father and his young son walk through burned America for the coast, scavenging food and avoiding cut-throat vigilantes who will gleefully kill them for their provisions and clothes. The setting here is an all-encompassing one; the ravaged, globally-warmed landscape of a nation – but it feels intensely intimate when told through the terrifying scope of this desperate father-and-son duo.

Olive Kitteridge is back

American author Elizabeth Strout is one of my favourite writers, and the imminent return of her most compelling character is a delightful prospect for any reader who enjoys smart, nuanced storytelling.

American author Elizabeth Strout is one of my favourite writers, and the imminent return of her most compelling character is a delightful prospect for any reader who enjoys smart, nuanced storytelling.

Olive, Again is being released next month, a follow-up to Strout’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2008 novel Olive Kitteridge, and I can’t wait to get my copy.

The PR blurb reads: ‘Olive, Again follows the blunt, contradictory yet deeply loveable Olive Kitteridge as she grows older, navigating the second half of her life as she comes to terms with the changes – sometimes welcome, sometimes not – in her own existence and in those around her.

‘Olive adjusts to her new life with her second husband, challenges her estranged son and his family to accept him, experiences loss and loneliness, witnesses the triumphs and heartbreaks of her friends and neighbours in the small coastal town of Crosby, Maine – and, finally, opens herself to new lessons about life.’

Rarely do characters come as multi-layered as Olive. Strout used all her creative expertise and deep understanding of human relationships to craft a powerful and quirky persona. Olive, an ill-tempered junior high school maths teacher who gives her husband short shrift at pretty much every opportunity, is brusque, flawed and fascinating in roughly equal measure.

Intellectually sharp yet lacking emotional intelligence, she is conflicted by, among many other things, feelings of guilt over an affair she has with a colleague at the school and severe frustration at her inability to show love and openness, particularly when in the company of her son.

Not one for social niceties, Olive’s bluntness and absence of self-awareness leads her down several rough and difficult paths. The character reached iconic status when portrayed by the mesmeric Frances McDormand in HBO’s 2014 TV series based on the book, the actress nailing the emotional complexity of Olive’s nature with exquisite compassion and discord.

It’s hard to believe that Olive Kitteridge was only Strout’s third published novel, considering the masterful poise and elegance of the writing style. The richness and authenticity of the title character is woven into a collection interrelated stories within the book, allowing the multiple perspectives to add wider context (a technique Strout echoes in the sublime Anything is Possible, released in 2017).

Olive, Again looks set to reaffirm Strout’s status as an extraordinarily gifted novelist whose place as one of the very best storytellers is already assured. Her vision and fully-rounded grasp of human behaviour – and her ability to translate that to the page – has given us an array of convincing characters – and they don’t come any more convincing than Olive Kitteridge.

“It turns out – I just wasn’t done with Olive,” Strout says. “It was like she kept poking me in the ribs, so I finally said, ‘Okay, okay’…”

[Top]Back Door to Hell now on sale

My new noir thriller Back Door to Hell has just been released by Fahrenheit 13.

My new noir thriller Back Door to Hell has just been released by Fahrenheit 13.

The publisher of the coolest collection of hard-boiled noir and experimental crime fiction on the planet (their words, but independently verified by several sources as absolutely true) publishes a new book on the 13th of every month, and January 2019 is the turn of my second full-length novel.

Back Door to Hell is a lean and pacey thriller that follows a young couple on the run after they steal a shedload of cash from a South London underworld crime boss.

More details about Back Door to Hell can be found here, while you can order or download the book direct from Fahrenheit 13 here or alternatively from Amazon on Kindle here and on paperback here.

It’s available at a fantastic price as well, from just £1.69 on ebook and £8.95 on paperback as a special new-release offer – so get in quick while the generosity lasts.

[Top]Why Dodgers is the book of the decade so far

Some books impress you for their slick writing style or their gripping story. Or their well-drawn characters or the captivating world they carve into your imagination. Dodgers doesn’t impress you. It chisels itself into you. It overpowers you. It stays with you.

Some books impress you for their slick writing style or their gripping story. Or their well-drawn characters or the captivating world they carve into your imagination. Dodgers doesn’t impress you. It chisels itself into you. It overpowers you. It stays with you.

Bill Beverly’s debut novel, published in 2016, came out of nowhere. The author, Associate Professor of English at Trinity University in Washington DC, doesn’t appear to be your average breakthrough novelist. At the time of writing he has yet to release another work of fiction, so cashing in while his name is hot isn’t on his agenda. According to interviews, he took his time penning Dodgers. It was worth the wait.

Giving himself no deadline as he wrote, he went against what many new writers are encouraged to do by agents in the modern publishing climate: plan everything with a long-running series in mind. Culminating far too often in a stale, recurring main character doing the same things again and again. No, Dodgers is purely a standalone tale – as all the great works of literature are.

Relayed in meticulous and economical third-person prose, we follow the journey of 15-year-old LA ghetto soldier East in what can be described as both a crime caper road trip and a coming-of-age saga, a contemporary thriller in dialogue and place with the stylistic undertones of a classic fable.

East, the eldest son of a troubled single mother, works for a drug peddling crew, just like pretty much everyone else he knows on the streets of the bleak African-American suburban landscape he has been raised, where the prospect of a violent death is constant. Resourceful, watchful and earnest, he has a natural flair for survival – and he’s going to need it.

The crew’s boss, Fin, needs a Wisconsin-based witness killed before the guy can testify against his nephew in an upcoming trial. Fin tasks East, his trigger-happy 13-year-old half-brother Ty, and two other young crew members – the overweight Walter and the cocky Michael – with travelling across America to carry out the hit.

Hopping on a flight is deemed by Fin as too traceable, so he sets them up with a van kitted out with sleeping quarters and money for petrol and basic leaving expenses. The gang of four are forced to ditch their IDs, cards, phones and weapons so they can’t be identified if caught. They are all given LA Dodgers baseball jerseys to wear as cover, hence the title.

East has never been outside his home city before, and the country and terrain is alien to all of them. It’s not long before the quartet are at odds with each other as well as the job, and it turns out that Ty is carrying, having hidden a small pistol in his trousers. It’s okay, he’s only the most unstable of the four in that van.

Things don’t go to plan. The four of them have to improvise under pressure as things fall apart amidst a backdrop of the Midwest heartland rusting to a slow death. Characters are tested as the drama heightens. The van is vandalised and spray-painted with a racial slur. The mission flips. East and Michael have a vicious punch-up, the group splits in stages.

East, wise but with plenty still to learn, naïve yet world-weary, carries so much weight and humanity. He is one of the most original and heartrendingly authentic characters I’ve ever read.

The book is sharp and taught, while everything that happens is driven by a convincing rationale. These characters don’t have many choices to make, if any at all. The plot is simple and tense; there is no need for coincidences or twists. The observations Beverly draws are insightful and relevant, the visuals he paints in your mind are startlingly real.

Dodgers has drawn merited comparisons to HBO gem The Wire and picked up Golden Dagger Awards for both best crime novel and best debut. For me, nothing has matched it for many years. We had some great releases in the noughties and Dodgers is, so far, the best book of the 2010s (is that what they’re calling this decade?).

Check it out. If you already have, read it again.

[Top]5 screenplays that every budding writer should read

When you’re honing your story writing craft, for a book or a script, there’s nothing quite like reading a quality screenplay to get the juices flowing.

The taut, compact nature of a finely tuned screenplay carries an effortless flow, sparkles with clarity and motion. The truly great screenplays, those born from an ambitious yet clearly defined vision and written with a visceral focus and relentless courage, are priceless gifts of inspiration.

So if you’re developing a concept for a story, or have hit a logjam in the writing process, run your eye over these top five movie screenplays that are readily available online. They sure have worked for me…

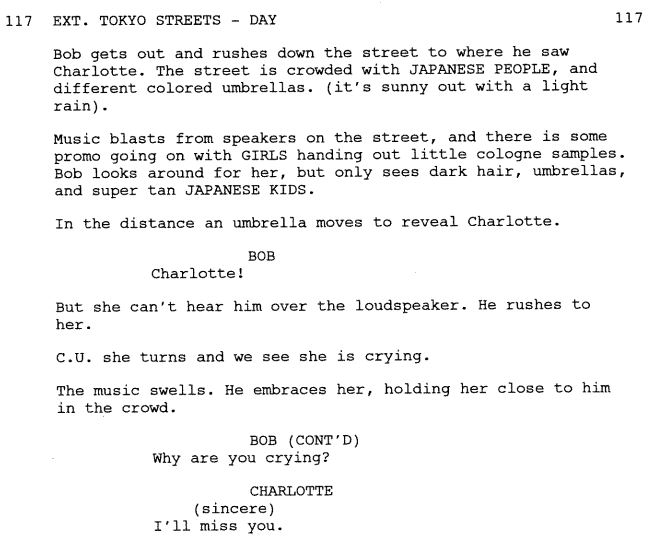

1. Lost in Translation, by Sofia Coppola

This is a prime example of how a series of soft and seemingly inconsequential scenes can drive a narrative along while maintaining interest and intrigue throughout. Coppola’s masterful use of understated dialogue and her development of two main characters at a poignant and relatable crossroads in their lives makes for a charming and moving story set in colourful Tokyo. Of course it helps when Bill Murray and Scarlet Johansson absolutely nail the leading roles.

2. Good Will Hunting, by Matt Damon and Ben Affleck

This duo’s big Hollywood break came in the form of this spellbinding script that served to launch their acting careers. Sharp dialogue and lively snippets of untamed youth give the story early momentum, before the drama really bounces off the page when the relationship between Will and his therapist – wondrously portrayed by Robin Williams in the movie – is fully explored.

3. The Usual Suspects, by Christopher McQuarrie

One of the more plot-driven screenplays in this shortlist, McQuarrie worked with director Bryan Singer on thrashing out a story about five criminals meeting in a police line-up and came up with this scintillating script. Every page is bursting with high-octane action or deep tension, while the canny twist ending is pulled off in exquisite fashion, turning Keyser Soze into one of the most iconic legends of 20th Century cinema.

4. The Big Lebowski, by Ethan & Joel Coen

‘This was a valued rug?’

‘Yeah man, it really tied the room together.’

There’s writing and then there’s the writing of the Coen brothers. Unique, hilarious and always utterly compelling, they construct characters like no other writer. At the heart of their films is the quirky dialogue of their leading protagonists, perhaps no better crafted than here with The Dude. Even if you’re not writing a comedy, the slick and effortless prose of this screenplay is a must-read.

5. Reservoir Dogs, by Quentin Tarantino (background radio dialogue by Roger Avary)

Another script famed for its peerless dialogue, it’s easy to forget how groundbreaking Tarantino’s debut film was considering his seminal future output and how many writers have tried and failed to imitate his style. So much more than a jewellery heist gone south, the searing pace and fluent exposition of this story results in a standout screenplay that any writer should draw inspiration from.

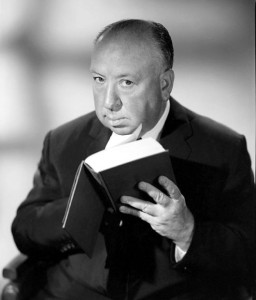

The 10 best books that inspired Hitchcock films

As a huge fan of Alfred Hitchcock’s movies, I’ve always been fascinated as much by the novels that inspired his directorial work as I have his famed skills for generating treasured moments of cinematic suspense.

As a huge fan of Alfred Hitchcock’s movies, I’ve always been fascinated as much by the novels that inspired his directorial work as I have his famed skills for generating treasured moments of cinematic suspense.

With that in mind, I have compiled my favourite – and what I consider the most accomplished – novels that Hitchcock later used as a basis to make a film. For the sake of sincerity, I’ve included some of the bigger-name titles that Hitchcock became best known for and just can’t be ignored, but I’ve also dug a little deeper to highlight some more unfamiliar works that deserve a mention.

Happy reading…

10. Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square

Written by journalist and crime reporter Arthur La Bern in 1966, this relentless novel was used by Hitchcock as the basis for his 1972 classic Frenzy.

The book tells the story of Bob Rusk, a sexual predator and serial killer in central London, but circumstantial evidence leads the police to prosecuting Rusk’s friend, Dick Blamey, for the string of crimes known as ‘the necktie murders’. Always partial to a tale of an innocent man getting stitched up, it’s easy to see what attracted Hitchcock to the story.

The movie represented an important chapter in the director’s legacy, seen as a triumphant return to Britain in what was his first film set there for more than 20 years (and only this third made in Blighty since moving to Hollywood in 1939). It also ended up being the penultimate film of Hitchcock’s career.

He asked Anthony Shaffer to adapt it for the screen, and there were some significant changes made from the book’s narrative. The light-hearted domestic scenes between the meticulous Inspector Oxford and his wife were entirely new creations (presumably Hitchcock wanted them to serve as a change of pace and tone from the brutality of the murders). The film was set in the era it was made – the early 1970s – while the novel takes place shortly after the Second World War (hence the title, taken from a line in the song ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’) and Blamey has an interesting backstory ignored in the film. In the novel he is a Royal Air Force veteran who feels guilty about his active role in the fire-bombing of Dresden, and his drunken references to his ‘killing’ past when first being interrogated by police about the necktie murders contributes to his unjust arrest.

La Bern was not a fan of what Hitchcock and Shaffer did with his story. In a letter to The Times, he called Frenzy a ‘distasteful film’, criticising the dialogue as ‘farce’ and adding: ‘I would like to ask Mr Hitchcock and Mr Shaffer what happened between book and script to the authentic London characters I created. Finally: I wish to dissociate myself with Mr Shaffer’s grotesque misrepresentation of Scotland Yard offices’.

9. The Manxman

One of writer Hall Caine’s greatest successes, this 1894 novel sold more than half a million copies and was translated into 12 languages.

Set on the Isle of Man, the book depicts a powerful love triangle between Kate Cregeen and her two friends, the illiterate but good-hearted Peter Quilliam, and the well-educated and sophisticated Philip Christian.

Notable for its regular use of Manx dialect unique to the Isle of Man, faithfully executed by Caine through unusual Manx Gaelic spellings, grammatical structure and phrases, the book received widespread critical acclaim, especially from high society. Britain’s Prime Minister of the day, Lord Rosebury, said: ‘It will rank with the great works of English literature’.

The novel was adapted twice for the stage and turned into a silent film by George Tucker in 1917 before Hitchcock developed it into his final silent movie in 1929.

Filmed almost entirely in the small Cornwall fishing village of Polperro, Hitchcock’s version was highly praised, his gripping portrayal of the love triangle emitting some of his most emotive characterisation and strongest imagery to date. Which is more than what the man himself thought of this work. Hitchcock later told Francois Truffaut it was ‘a very banal picture’, adding the ‘only point of interest about that movie is that it was my last silent one.’

8. The Thirty-Nine Steps

Now we’re on to one of the big hitters. This high-octane, pacey novel with its lethally sharp prose reads as smoothly as any sparse, contemporary thriller – Christ knows how rapid it must have felt on its release in 1915.

By far the most famous novel by Scottish author John Buchan, The Thirty-Nine Steps has never been out of print since. It was in fact Buchan’s 17th published book, and catapulted him from a promising 39-year-old writer into a best-selling author of highly-acclaimed thrillers and adventures over the following two decades.

Despite the book perhaps being most remembered for its glorious evocation of the rolling Scottish countryside, of its 10 chapters only three and a half are actually set in Scotland. Main protagonist Richard Hannay (wonderfully played by Robert Donat in Hitchcock’s 1935 adaptation) offered the reading public in the first year of WW1 something relatively fresh; a physically dynamic anti-hero, cool and brave with the intellectual and emotional prowess that enabled him to turn detective under pressure (skills that earned him a leading role in four further Buchan books) while still maintaining a stiff upper lip.

Although the book was a pioneer of the ‘man-on-the-run’ archetypal thriller that would become a much-used plot device, Buchan’s enthusiasm for inserting unlikely events into the plot that the reader would only just be able to believe does give the book a somewhat fantastical edge, but it’s a barnstorming read nonetheless.

Hitchcock’s film does divert somewhat from the book, creating the music hall scene and the two major female characters for cinematic effect. In the book the 39 steps refer to literally that, while in the movie the 39 steps is a clandestine group of spies.

7. The Lodger

Prolific London-born novelist Marie Belloc Lowndes is said to have gotten the idea for this story after overhearing a dinner conversation where a guest was telling another that his mother’s butler claimed to have once rented a room to Jack the Ripper. That was the spark that eventually led in 1913 to her releasing The Lodger, a fictional take on the gruesome Whitechapel murders of 1888. It sold more than a million copies.

The style of the story is pure Hitchcock – the horror builds slowly and skilfully as landlords Richard and Ellen Bunting gradually begin to fear that a recent lodger they’ve taken on upstairs in their home, a Mr Sleuth, could be the mysterious killer of several local women.

Using the story, as well as the play ‘Who is He?’, a comic stage adaption of the novel co-written by Belloc Lowndes and playwright Horace Annesley Vachell, Hitchcock delivered one of his finest silent movies in 1927, titled ‘The Lodger: A story of the London Fog’. Oozing with psychological suspense, menacing camera angles and claustrophobic lighting, the film was also Hitchcock’s first foray into sexual fetishism and psychodrama.

Interestingly, Hitchcock wanted the film to end with ambiguity over whether the lodger was the serial killer, but he later claimed the studio, Gainsborough, wouldn’t let popular leading man Ivor Novello be considered as a villain. ‘We had to change the script to show that without a doubt he was innocent,’ Hitchcock said.

6. Before the Fact

Written in 1932 by Anthony Berkeley, under the pen name Francis Iles, this bold novel was adapted by Hitchcock into his 1941 film Suspicion.

Far from penning a popular whodunit, Berkeley ensured the readers of Before the Fact knew who the villain was pretty early on. Johnnie Aysgarth has married Lina McLaidlaw for her family’s money. Over the years that follow Lina gradually learns that Johnnie is a compulsive liar, thief, embezzler, adulterer and in fact plans to murder her. At the end of the novel, which has spanned 10 years, Lina, flu-stricken and mentally unhinged but still desperately in love with her husband, swallows a cocktail she knows Johnnie has poisoned. Her death is imminent, but not conclusive, when the book ends.

Hitchcock’s film covers much of this dark and suspenseful mood, but differs from the book in that Johnnie’s ‘murderous’ intentions are portrayed as a product of Lina’s imagination. In a similar predicament to The Lodger, there was also apparent studio interference with the plot ending, with RKO Radio Pictures said to be not all that keen on having one of Hollywood’s most heroic actors, Cary Grant, being shown on screen as a devious killer. Despite not being able to play Lina in the emotionally complex and compelling ending described in the book, Joan Fontaine’s depiction of the character in the film was strong enough to earn her the 1941 Academy Award for Best Actress.

5. Psycho

I suppose it’s fair to say the film has eclipsed the novel on this one. Robert Bloch’s 1959 book was an instant hit, influenced from the pulp principles of the day – Psycho is fast-paced, terrifying, captivating and utterly disturbing, all laced with a healthy dose of murder, madness and mayhem.

Hitchcock’s seminal movie of the same name came out just a year later, the speed of the adaption perhaps an indication of how powerful a novel Hitchcock regarded it to be (‘Psycho all came from Robert Bloch’s book,’ he said, albeit nine years later). It’s one of the director’s most faithful adaptions, the narrative skeleton of the book retained throughout the feature, with suspense, mystery and horror leading the way.

One difference was Hitchcock’s clarity of focus when it came to driving the story through certain characters’ perspectives. Bloch was happy to shift the point of view throughout his narrative; the opening chapter is from Norman’s perspective, the second Mary’s (who was called Marion in the film), the third is split between the two of them, and we’re back in Norman’s head in chapters four and five. Some of the latter chapters are written in the style of neutral third person. Hitch had a clear agenda of who he wanted the audience to bond with; we’re solely with Marion from the start until she meets her maker in the shower; then it’s largely Norman.

In Bloch’s chapters written from Norman’s POV, the writing is exceptional. His blackouts appear so genuine that the reader is compelled to believe that his jealous mother truly is Mary’s killer.

4. Marnie

Another example of great, daring literature, Winston Graham’s psychological thriller Marnie is a hugely suspenseful and captivating read.

A prolific author well known for his series of Poldark historical novels, Graham released Marnie in 1961 to great acclaim but also a fair bout of controversy. The title character is a beautiful embezzler (played by Tippi Hedren in Hitchcock’s 1964 film) whose life of crime was sparked by a traumatic incident in her early childhood that she and the audience only get to truly understand at the end of the story.

After getting caught stealing from her employer, Mark Rutland, who also happens to be in love with her, Marnie is forced into marrying him in order to avoid jail. The marriage evolves into a complex but gripping web of deception, misinterpretations, mistakes and disputes, including a rape scene. Mark feels he loves her and is doing the right thing to get Marnie over her psychological problems; Marnie feels she was blackmailed into the marriage.

As the plot thickens, the book becomes a crime novel less centred around crime but by the mystery of Marnie’s secret past (and that of her mother’s), her core identity, and the complex issues of psychiatry. Written as a first person account by Marnie, the book is a finely-tuned introspective character piece that Hitchcock was fascinated by.

So determined to keep the divisive rape scene in his 1964 movie, Hitchcock dismissed screenwriter Evan Hunter from the project, who pleaded that the sequence be dropped because the audience wouldn’t bond with the male lead (played by Sean Connery). Replacement Jay Presson Allen shared Hitchcock’s keenness to include the scene.

There were some alterations made from the book though; Hitchcock changed the setting from England to the USA, thus losing the quintessential English ambience of the book according to some critics, a key character from the book, a lechy executive who pursues Marnie, is omitted altogether and the unravelling of Marnie’s childhood trauma that became the source of her emotional problems is a lot more simple and optimistic than the darker, more complex version in the novel.

3. The Rainbird Pattern

Plymouth-born thriller writer Victor Canning published 61 books in his lifetime, but one is widely regarded as by far and away his best – The Rainbird Pattern, winner of the Crime Writers’ Association Silver Dagger in 1972.

Elderly spinster Grace Rainbird, trying to bring missing elements of her family together before her time is up, promises spirit medium Blanche Tyler a large sum of money to locate her illegitimate nephew Edward Shoebridge. Blanche and her boyfriend, George Lumley, go desperately looking for Edward, who so happens to be living under a different name and co-ordinating several kidnappings of prominent officials, with his next project likely to rake in his largest ever ransom – the abduction of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

This split-level story is woven together with deft skill, Canning building the suspense and heightening the violence beautifully before unleashing an unpredictable ending. The plot is so seamless and commanding that it’s fair to say this is a prime example of a book triumphing over a Hitchcock film.

Titled ‘Family Plot’, Hitch’s 1976 movie turned out to be his final motion picture before his death four years later. The setting was switched from the south of England to southern California, and the charismatic features of Blanche and her jack-of-all-trades quirky partner Lumley were magnified so the tone of the film came across as more of a black comedy. Although personally I’ve always thought Family Plot an invigorating and much under-rated film, its reception in no way matched the glowing reviews attributed to The Rainbird Pattern.

2. Rebecca

When it comes to linking Hitchcock with fiction, Daphne du Maurier is pretty much literature royalty. Her short story ‘The Birds’ went on to provide the basis for one of the director’s most iconic hits, but her glorious 1938 novel Rebecca goes down as a genuine literary masterpiece.

An outstandingly evocative opening sentence (‘Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again…), the razor-sharp description of a haunting fictional estate, a compelling combination of lead characters and a fascinating mystery all add up to a classic gothic romance thriller.

‘Very roughly, the book will be about the influence of a first wife on a second,’ wrote du Maurier in her notes. ‘Until wife 2 is haunted day and night… a tragedy is looming very close and crash! Bang! Something happens.’

Her tale of jealousy, bitterness, identity, mystery and secrets broke the mould of themes being explored by her contemporaries of the day. She sidestepped issues such as war, religion, poverty, art and existentialist streams of consciousness to thread together a more simple narrative about love, adventure and mystery and the reading public lapped it up, its appeal enduring to this day.

Hitchcock did a marvellous job adapting it for the screen in 1940, his first project after moving to America. As well as being technically brilliant (it won the Academy Award for Best Picture and Best Cinematography) the film largely maintained the emotional drama of the book. There was one plot detail change though; in order to comply with the Hollywood Production Code, which outlined that the murder of a spouse had to be punished, the book’s revelation that Max killed Rebecca had to be altered. He considers killing her as she taunts him into believing that she’s pregnant with another man’s child, but she is in fact suffering from incurable cancer and has a motive to commit suicide and punishing Max from beyond the grave, so her death is declared a suicide.

1. Strangers on a Train

Before Patricia Highsmith famously created the anti-hero Tom Ripley, she penned the breathtakingly sharp, taut and dark ‘Strangers on a Train’ in 1950, which remains one of the finest blueprints of noir fiction to this day.

Architect Guy Haines is desperate to divorce his unfaithful wife, Miriam. While on a train he meets coarse alcoholic Charles Anthony Bruno, a sociopath who suggests they ‘exchange murders’. Bruno will kill Miriam if Guy offs Bruno’s father; neither of them will have a motive and the police will have no reason to suspect either of them. Guy thinks it’s a joke, but the deranged Bruno moves first and kills Miriam. Panic, guilt, a chaotic game of cat and mouse, and further tragedy all follows.

Highsmith flourishes in drawing the reader in by stacking complications on top of each other as the stakes rise, while the book also serves as a skilful examination of the allure of chance meetings, and of why it seems so much easier for us to unburden ourselves to strangers, to let our guard down in unexpected moments of intimacy.

Hitchcock’s 1951 adaption received deserved praise as a creative force in its own right, but there were flaws. Hitch later admitted to Francois Truffaut that casting Farley Granger as Haines was a mistake (‘I would have liked to see William Holden in the part because he’s stronger’). The character of Bruno, meanwhile, was softened into more of a dandy charmer, while he also dies in a climactic scene on a merry-go-round rather than in a boating accident as he does in the book.

The homoerotic subtext – hinted at in the novel – is expressed more vividly in the film, possibly because Hitchcock thrived in subtly developing gay characters in his 1948 feature Rope (also starring Granger), and enjoyed presenting his audiences with sexually ambiguous characters.

Highsmith praised Robert Walker’s performance as Bruno, but wasn’t best pleased with the decision to turn Guy from an architect into a tennis player, nor with the fact that Guy does not, as he does in the novel, go through with murdering Bruno’s father.

[Top]Standalone books v series

As you can see from my influences page, many of my favourite books are standalone novels, but there are also some works that form part of a series.

Many a literary agent/editor/publisher will tell you that, particularly with crime fiction, long-running serials sell much better than standalones. Beginner writers are continually told by industry insiders that, if they want to break into the market, they stand a much better chance if they pen a manuscript ensuring the main character will return (preferably on many occasions) rather than fashion a one-off tale.

But why is this? Why are the series more appealing to readers and therefore more successful in the marketplace? Here are my thoughts, analysing the pros and cons of both standalones and series.

Standalones – the pros

By their very nature, standalones generally depict a very passionate story. The author has composed the tale based on a burning theme they wanted to pursue, a poignant story they wanted to unravel and a certain message they wanted to transmit to the reader. And they have been free to express that story in any way they see fit, tying up any loose ends (to an ultimate conclusion) if they wish, exploring any theme or location to the very limit, knowing they or their characters will never go down this road again. The shackles aren’t as much off; they were never on in the first place.

Authors can also lead their main protagonist down any dark alley they want to, even if the outcome proves fatal. The reader is on edge because they know that the character they’ve related to and connected with faces any degree of peril. The writer is doing it their way; they are pulling all the strings because they are under no pressure to sustain any part of the story or a character for a future instalment.

The authors are writing with their hearts, holding nothing back. Fire is in the belly as well as the fingertips as they unleash their saga. Whenever a media outlet releases a list of the greatest (or most popular) novels of all time, standalones are always there standing proud. For Whom the Bell Tolls, Catch 22, David Copperfield, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Day of the Jackal, The Killer Inside Me, The Great Gatsby, American Psycho, Scoop, Disgrace, Libra, The Road, No Beast so Fierce and many, many more. Works that carry a central emotive core and bare the author’s soul; unbridled creations and unique artefacts.

Standalones – the cons

Imagine if Ian Fleming, having written his heart out on his debut novel Casino Royale, had left James Bond at that point and moved on to another project, 007 confined to history in 1953. Standalone books provide us with great high-stakes tales but there’s the downside that stopping at one story prevents further development of a fascinating character, denying us the prospect of enjoying this protagonist taking on more challenges and allowing us to bond with them further. There’s no doubt that the huge cultural impact certain recurring characters have had on the world (Bond, Sherlock Holmes, Philip Marlowe et al) has done wonders for crime fiction and duly rewarded their authors with much deserved adulation.

Another point to consider here is that sometimes a standalone can be too long (Don DeLillo’s Underworld breached into this territory, as did Against the Day by Thomas Pynchon), possibly to the extent that you feel the author probably considered splitting it into a mini-series somewhere along the way but stuck with it anyway. And sometimes the total freedom an author enjoys with a standalone can lead to self-indulgence and a story/theme that winds out of control, but in a trade that depends on huge reserves of creativity and bravery, that’s often a small price to pay.

Series – the pros

Within the context of a series, particularly a long-running one, absorbing characters can be further enriched so they become legends, both literary and cinematic. There is plenty of room in standalones to develop and focus on characterisation (as there is setting and plot) of course, but with a series we just get to spend more time with our heroes, or at least people we’re fascinated by and have formed a connection with.

Another good thing about serials, especially in crime fiction, is that the cream of writing talent often rises to the top; series formats have allowed some magnificent writers to forge thoroughly deserved successful careers. Not many publishers dish out multi-book deals to poor writers. The likes of Patricia Highsmith (Thomas Ripley), Ian Rankin (Rebus), Mark Billingham (Thorne), Ken Bruen (Jack Taylor), James Sallis (Lew Griffin & The Driver), Adrian McKinty (Sean Duffy & Michael Forsythe), James Lee Burke (Dave Robicheaux), James Crumley (Milo Milodragovitch & C.W. Sughrue) and Ray Banks (Callum Innes) have all developed as writers over the course of sticking with their returning characters, the pressures of meeting their regular instalments perhaps forcing them to harness their craft in a quicker – and ultimately more confident way – than they otherwise would have done.

Serials also offer authors the opportunity to write a smartly conceived mini-series based mainly on theme rather than one principal character. With these each book is often significantly different in terms of timeframe or minor characters becoming major ones in the next book and vice versa. David Peace’s Red Riding quartet would fall into this category, a wonderful series that wouldn’t have been anywhere near as powerful as a standalone, nor a long-running series. James Ellroy’s LA quartet and Underworld trilogy also spring to mind here, as do Scott Phillips’s The Ice Harvest and The Walkaway, the narratives of those two connected works separated by 10 years.

Series novels also tend to get talked about more in social circles (so I’ve noticed anyway), allowing more opportunities for readers to share their experiences. An extensive, consistent body of work seems to bring people together more than standalones appear able to, and anything that gets people talking about reading, whether it’s at home, work, the beach or on social media, is a positive thing.

Series – the cons

The downside of an author under pressure to publish an annual instalment of a long-running series is of course the danger that they end up just churning them out. Just as their main character may have helped that author achieve fame, the process can also push them over the edge, their creative forces crashing and burning. Pumping out a novel a year to meet marketplace pressure can be a trap to penning prose unworthy of the writer and their initial ambitions, and that’s a real shame.

There’s also the danger of too many new writers feeling they have to launch their career with a main character that has ‘plenty of legs’, which all too often leads to the creation of a cliché-ridden detective we’ve all read enough of. You know the type; divorced, has a troubled relationship with his teenage son/daughter who’s growing up too fast, puts his work before his health and lifestyle, he’s the only one who despises corporate suits and bureaucracy, he unwinds in the winter evenings by listening to music anyone under 35 would scoff at, with a stiff drink in his hand. And the evil activities of each particular rival he encounters eventually results in the duo facing off in a duel, where the arrogance of the criminal leads to victory for the humble hero.

The readers lose out big time here. Not only can the returning character lose their appeal, but the plot can also lose its punch. Let’s face it, as the stakes rise in the final third we always know the main character will get out of this latest scrape relatively unscathed because they’ll be back for another adventure next year.

An example of an author who made his name with a solid series but broke free of the format to express himself in standalones is Dennis Lehane. After five instalments of blue collar detective duo Patrick Kenzie and Angela Gennaro, he pulled himself away to write Mystic River (later adapted into a Hollywood blockbuster) and then Shutter Island (ditto), two superb one-off thrillers that were both critically acclaimed and commercially successful.

Series are obviously easier to market. The industry loves them, often to the extent that a new release is promoted as a series right from the off. The first time I saw publicity for Malcolm Mackay’s debut novel The Necessary Death of Lewis Winter, it was labelled as the first instalment of ‘the Glasgow trilogy’. Almost as if his agent pitched the debut manuscript to a publisher who said “Forget it – unless your guy’s got two more up his sleeve, then I can call it a trilogy and I’ll have something to sell”.

David Peace’s ‘Tokyo trilogy’ was marketed as such on the release of the first instalment in 2007. After releasing the second in 2009, Peace drifted away from the concept and wrote Red or Dead, his standalone football novel about the late Bill Shankly. At the time of writing (September 2014) there’s still no sign of the final part of the Tokyo trilogy. Perhaps a sign that the desire for a series is more pressing for the marketing people than it is for the authors.

[Top]