10 thrilling cat-and-mouse chases

I recently wrote an article for the Criminal Element website about my favourite fictional chase sequences that helped inspire my new novel Back Door to Hell.

I recently wrote an article for the Criminal Element website about my favourite fictional chase sequences that helped inspire my new novel Back Door to Hell.

The piece, titled ‘The best cat-and-mouse chase thrillers in crime fiction’, explores 10 examples of captivating stories – ranging from the classic to the modern – that feature a significant chase as part of the plot, from police pursuing criminals to villains hunting after each other.

Take a look and let me know at @PaulJGadsby if you think I’ve missed any crackers out.

Glowing reviews for Back Door to Hell

My newly-released noir thriller Back Door to Hell is going down a storm with crime fiction critics and fans.

My newly-released noir thriller Back Door to Hell is going down a storm with crime fiction critics and fans.

Early reviews have praised the novel’s pace, characterisation and the tense storyline which keeps readers on the edge of their seat until the end.

American freelance writer and book reviewer Brian Greene posted a review on the highly revered website Criminal Element, labelling Back Door to Hell ‘an exhilarating thriller’ and ‘a novel that seems ripe for film adaptation.’

He adds: ‘What sets Back Door to Hell apart is its naturalness… While other contemporary crime fiction scribes go out of their way to make sure their books have the fashionable noir qualities, there’s no such affectation in Gadsby’s work. His characters are believable, his storylines are interesting, and his writing is organic. And he excels at revealing the multiple dimensions of his characters’ life situations and internal makeup.’

Meanwhile on another illustrious crime website, Crime Fiction Lover, reviewer Louis Bravos said the novel was a ‘brilliant slice of British noir which packs a lot of punch and says a lot about modern-day Britain.’

His review adds: ‘Back Door To Hell is as tense and edge of your seat as any heist novel, packing a lot into 200 pages plus change. What really separates it from others in the genre is how believable and contemporary it is.’

Over on Goodreads, one reviewer said: ‘The action & plot twists alone are enough to keep you turning the pages… The prose is smooth & clean with enough detail to provide atmosphere but never at the expense of pace… As I was reading, I couldn’t help but think ahead & wonder how it would end. There are several choices, at least one of which would have been disappointingly unrealistic. Thankfully, the author chose an ending that is sobering yet oddly hopeful. And now I have a new (to me) author to follow.’

The reviews on Amazon have also been extremely positive. One review said: ‘Fast moving story well written. Couldn’t put it down for wanting to find out the next twist and turn. Lots of action with plausible characters.’

Another wrote: ‘What a great book, fast, pacey, I couldn’t put it down. I would highly recommend it, you won’t be disappointed,’ while another said: ‘A fabulous read! I was engrossed in the story and really rooted for the main 2 characters. I highly recommend this book.’

‘A thrilling read from start to finish,’ wrote another. ‘A great plot and moments of genuine tension throughout with a climax that plays on the emotions. Gadsby sets the scene from the mean streets of south-east London to a cross-country chase superbly. A real page-turner.’

The popular, award-winning ‘Beardy Book Blogger’ also loved the novel, saying it was ‘a true rollercoaster of a book. It is short and to the point and really draws you into the story. There is no dead air here; Paul Gadsby keeps the pace high and the tension is palpable throughout.’

Click here for more details about Back Door to Hell and how to buy direct from publisher Fahrenheit Press.

[Top]Back Door to Hell now on sale

My new noir thriller Back Door to Hell has just been released by Fahrenheit 13.

My new noir thriller Back Door to Hell has just been released by Fahrenheit 13.

The publisher of the coolest collection of hard-boiled noir and experimental crime fiction on the planet (their words, but independently verified by several sources as absolutely true) publishes a new book on the 13th of every month, and January 2019 is the turn of my second full-length novel.

Back Door to Hell is a lean and pacey thriller that follows a young couple on the run after they steal a shedload of cash from a South London underworld crime boss.

More details about Back Door to Hell can be found here, while you can order or download the book direct from Fahrenheit 13 here or alternatively from Amazon on Kindle here and on paperback here.

It’s available at a fantastic price as well, from just £1.69 on ebook and £8.95 on paperback as a special new-release offer – so get in quick while the generosity lasts.

[Top]Publishing deal for Back Door to Hell

I’m delighted to reveal that my new crime novel, Back Door to Hell, will be published by Fahrenheit 13 in the New Year.

I’m delighted to reveal that my new crime novel, Back Door to Hell, will be published by Fahrenheit 13 in the New Year.

The publisher’s senior editor, Chris Black, and I have been working on the edits over the last few months and the book is all set for release in January 2019.

Fahrenheit 13 is an imprint of Fahrenheit Press, one of the coolest, bravest and most important independent publishers around, devoted to providing readers with the finest and most original crime fiction on the planet.

Back Door to Hell is a fast-paced noir thriller that follows a young couple who, desperate to improve their lives, embark on an audacious cash robbery that results in a cat-and-mouse chase around the country.

The book is my second full-length published crime novel, after Chasing the Game, and my second collaboration with Fahrenheit Press after my short story Washed Up was selected to be included in their groundbreaking Noirville anthology following an open competition.

More news about Back Door to Hell will be announced here in due course. Watch this space and all that…

[Top]6 scintillating scenes set in hotels

When hotels crop up in fiction, the story tends to crank up a notch. They serve as a base for characters in transition, often marking a major turning point in a protagonist’s trajectory.

When hotels crop up in fiction, the story tends to crank up a notch. They serve as a base for characters in transition, often marking a major turning point in a protagonist’s trajectory.

With the comfort of home or familiarity of work out of the equation as a setting, hotels are natural havens for dark reflection, for brewing trouble.

They are places to set up an illicit rendezvous, to seek shelter in an emergency, to lay low and heal wounds, to hatch a plan, to break up a defining journey, to let loose on holiday, to discover a secret.

And they generate change. Characters rarely check out in the same state or mood as when they arrived…

No Country for Old Men

Let’s kick off with this Cormac McCarthy cracker that treats us to hotel scenes aplenty. There’s Llewelyn Moss holing up with a satchel containing $2.4m in stolen cash that hired hitman Anton Chigurh nearly snatches from his grasp in a Texas motel, not to mention Chigurh patching himself up from bullet wounds later on as the brutal chase spills south. But my abiding memory of this book is a recovering Chigurh taking out rival hitman Carson Wells, who is also on the trail of the loot, in Wells’ hotel room near the Mexican border. The two share some candid words in the darkened room as a poised Chigurh holds his shotgun at Wells, McCarthy’s pitch-perfect dialogue making it feel like a privilege to eavesdrop on this private discourse between two pro killers as death looms.

Just do it.

Yes, they always say that. But they don’t mean it, do they?

The Eye of the Beholder

A rogue PI follows Joanna Eris, a scheming serial killer, in this creepy cross-state thriller from Marc Behm. Fascinated by her actions, the PI, unbeknown to Joanna, cleans up after her murders as she vaults from city to city seducing rich men and killing them. During a stay in New York, an off-duty NYPD sergeant sees her fleeing the scene of a minor road accident and follows her back to her hotel room. Inside, he asks her questions and is met by a wall of evasiveness as the tension rises. Sensing she has something to hide, the cocky officer threatens to arrest her. For the first time we sense Joanna’s world falling apart, but she gathers herself and identifies the sleazy officer’s weakness. As he moves closer suggesting a sexual bribe, she swipes his pistol from his holster and shoots him dead. The snooping PI, having bugged the room, hears everything and is relieved that his voyeuristic adventures can continue.

The Shining

Stephen King in his pomp, creating one of the most haunting settings ever with the isolated Overlook Hotel in the Colorado Rockies. Winter caretaker Jack Torrance is starting to suffer from cabin fever in the vast and vacant hotel, his erratic state putting his wife and son in danger. Out of all the chilling scenes, the most telling in which our view of Jack changes forever is when he walks into the huge ballroom where the bar, as we well know by now, has no alcohol. But in a flash the shelves are lined with bottles of liquor and a bartender, Lloyd, is serving Jack drinks. Jack talks about his woes, Lloyd is a good listener. The presence of another character brings a new dynamic to the story, the fresh voice penetrating the mind of the reader. King makes it clear that Lloyd is a ghost and the drinks are imaginary, leaving us in fear of Jack’s sanity as Lloyd, speaking on behalf of the hotel’s malicious spirit it seems, advises Jack to ‘correct’ his family. There’s no turning back now.

The Motel Life

This 2006 debut novel from Willy Vlautin is a taut and compassionate tale of two destitute high-school-dropout brothers, Frank and Jerry Lee, set in Nevada. Forced to go on the run after Jerry Lee, drink driving one night, accidentally hits and kills a teenage cyclist, they head for Montana, sleeping in their car on some nights and in cheap motels on others. Vlautin skilfully explores the fears, frustrations and faded dreams of two low-income young men left behind by society and desperately short of luck. Riddled with guilt from the fatal accident, Jerry Lee shoots himself in the leg. While in hospital recuperating, he persuades Frank to break him out so they can continue their journey. In a motel in Elko, the brothers spend the night talking about their lives and fight to raise each other’s spirits in a heartrending scene, as Jerry Lee’s wounds worsen.

The Day of the Jackal

The Jackal, on a hired mission to assassinate Charles de Gaulle in 1960s Paris, has the French police on his tail and is starting to feel the pressure in this Frederick Forsyth classic. During a brief stay in a swish hotel in the south of France we see a different side to him as he seduces an older French woman. Although his survival instincts are part of the exercise (he later takes refuge in the woman’s chateau before he is forced to kill her when she discovers his rifle amongst his belongings), the scene stands out as it shows the Jackal acting on a motivation other than his ultra-professional drive to complete his mission. After the killing, the Jackal is no longer seen by the reader as unflappable.

Psycho

Couldn’t really miss this one out now, could I? Robert Bloch’s 1959 hit is one of the most absorbing mysteries ever written and served as a blueprint for how to weave deep psychological analysis into the flow of a thriller. My favourite scene in the Bates Motel is when Norman spies on Mary through the drilled hole in his office wall that runs into her bathroom after they’ve just shared an awkward dinner at the house following her late arrival with no open restaurant nearby. Drunk, confused, angry and excited, Norman gets dizzy at the sight of Mary undressing (she was swaying back and forth . . . and she was wavy, and he couldn’t stand it, he wanted to pound on the wall, he wanted to scream at her to stop) and, we’re led to believe at this stage, passes out in the office chair just before Mary enters the shower.

And another 6 that almost made it…

The Spy Who Loved Me, by Ian Fleming.

Pessimist, by Chris Rhatigan

Galveston, by Nic Pizzolatto

Jack’s Return Home, by Ted Lewis

1980, by David Peace

Those Who Walk Away, by Patricia Highsmith

Don DeLillo’s Libra – 30 years on

This month marks the 30th anniversary of the release of what I regard as the most powerful book ever written about the JFK assassination – Libra by Don DeLillo.

This month marks the 30th anniversary of the release of what I regard as the most powerful book ever written about the JFK assassination – Libra by Don DeLillo.

Released on 15 August 1988, this extraordinary novel blends historical fact and fictional speculation to offer a mesmerising account of the infamous murder of President John F. Kennedy in his motorcade in downtown Dallas 1963. The tale is told purely from the perspective of the man predominantly – and officially at least – held responsible for the killing: Lee Harvey Oswald.

Whether Oswald was the lone assassin is still open to fierce dispute, with many ballistics experts, historians and witnesses still offering to this day conflicting accounts of what transpired during that fateful November lunchtime.

Despite the government-backed Warren Commission report concluding that Oswald acted alone in firing three shots from his rifle from the sixth floor of the Texas Schoolbook Depository, there is no universal consensus on several details. The number of gunmen involved, the calibre of the weaponry used, the quantity of rounds fired and from which location(s), as well as the overriding motive, are all still up for debate.

In Libra (the title being Oswald’s astrological sign), DeLillo explores what he regards as the most likely possibility: that the hit was instigated by disgruntled CIA operatives carrying deep anti-Castro ideology that Kennedy was failing to prioritise. In this version of events Oswald’s shots were – unbeknown to him – supplemented by more deft marksmanship from the grassy knoll, a controversial spot many have claimed to be the most realistic source of the fatal headshot captured so vividly and brutally in the Zapruder film.

“I could perhaps have written the same book with a completely different assassination scenario,” DeLillo said in a Rolling Stone interview in 1991.

But the technical details of the hit are not why people should read this book. They should read it for DeLillo’s unflinching yet visceral depiction of Oswald’s painful and pitiful journey.

Starting with a haunting scene of him riding the subway through the Bronx during a turbulent two-year stay in New York in his early teens, we get an immediate sense of this misfit searching for meaning. Standing pressed against the window taking the curves, jerks and pushes of the train, he finds that the drunks, pickpockets and dark tunnels of the bowels beneath the city hold more allure for him than the glittering streets above. It’s so real you feel you can almost reach out and touch him.

The book follows Oswald’s adolescent years followed by a failed stint in the US Marine Corps, an ultimately failed defection to the old Soviet Union and his violent marriage. Then it cranks up, covering his desperate but fruitless struggle to leverage his passionate communist views into a position of authority within high-ranking pro-red social circles on his return to the USA.

DeLillo skilfully paints a picture of this vivid outcast – intellectually, socially, physically and emotionally – as he constantly strives to find his place, to earn the respect he craves.

There is no effort to portray Oswald sympathetically, or even critically. He is carved open and exposed for readers to draw their own conclusions of the man as the narrative weaves towards Dealey Plaza. The internal conflicts and self-contradictions Oswald battles with pull him closer to the surface, sharpening the hazy sketches of his personality provided by numerous documentaries.

We learn that Oswald loves his young Russian wife yet hits her, he would do anything for his children but hatches a plan that draws him away from their clutches. He is well-read but dyslexic, he is thoughtful yet not smart, he is driven but also confused.

No one has analysed the complex and infuriating character that is Oswald through such a deep lens. The inner intensity of Oswald’s escape from the depository, his subsequent shooting of a police officer in the street and his arrest in a nearby cinema, and his final hours that follow is gloriously seamless and utterly compelling.

Libra won The Irish Times’ first International Fiction Prize and, three decades on, is still a classic example of how to get under the skin of a multi-layered persona in the public eye and truly dissect every sense of their being.

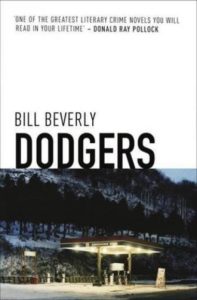

[Top]Why Dodgers is the book of the decade so far

Some books impress you for their slick writing style or their gripping story. Or their well-drawn characters or the captivating world they carve into your imagination. Dodgers doesn’t impress you. It chisels itself into you. It overpowers you. It stays with you.

Some books impress you for their slick writing style or their gripping story. Or their well-drawn characters or the captivating world they carve into your imagination. Dodgers doesn’t impress you. It chisels itself into you. It overpowers you. It stays with you.

Bill Beverly’s debut novel, published in 2016, came out of nowhere. The author, Associate Professor of English at Trinity University in Washington DC, doesn’t appear to be your average breakthrough novelist. At the time of writing he has yet to release another work of fiction, so cashing in while his name is hot isn’t on his agenda. According to interviews, he took his time penning Dodgers. It was worth the wait.

Giving himself no deadline as he wrote, he went against what many new writers are encouraged to do by agents in the modern publishing climate: plan everything with a long-running series in mind. Culminating far too often in a stale, recurring main character doing the same things again and again. No, Dodgers is purely a standalone tale – as all the great works of literature are.

Relayed in meticulous and economical third-person prose, we follow the journey of 15-year-old LA ghetto soldier East in what can be described as both a crime caper road trip and a coming-of-age saga, a contemporary thriller in dialogue and place with the stylistic undertones of a classic fable.

East, the eldest son of a troubled single mother, works for a drug peddling crew, just like pretty much everyone else he knows on the streets of the bleak African-American suburban landscape he has been raised, where the prospect of a violent death is constant. Resourceful, watchful and earnest, he has a natural flair for survival – and he’s going to need it.

The crew’s boss, Fin, needs a Wisconsin-based witness killed before the guy can testify against his nephew in an upcoming trial. Fin tasks East, his trigger-happy 13-year-old half-brother Ty, and two other young crew members – the overweight Walter and the cocky Michael – with travelling across America to carry out the hit.

Hopping on a flight is deemed by Fin as too traceable, so he sets them up with a van kitted out with sleeping quarters and money for petrol and basic leaving expenses. The gang of four are forced to ditch their IDs, cards, phones and weapons so they can’t be identified if caught. They are all given LA Dodgers baseball jerseys to wear as cover, hence the title.

East has never been outside his home city before, and the country and terrain is alien to all of them. It’s not long before the quartet are at odds with each other as well as the job, and it turns out that Ty is carrying, having hidden a small pistol in his trousers. It’s okay, he’s only the most unstable of the four in that van.

Things don’t go to plan. The four of them have to improvise under pressure as things fall apart amidst a backdrop of the Midwest heartland rusting to a slow death. Characters are tested as the drama heightens. The van is vandalised and spray-painted with a racial slur. The mission flips. East and Michael have a vicious punch-up, the group splits in stages.

East, wise but with plenty still to learn, naïve yet world-weary, carries so much weight and humanity. He is one of the most original and heartrendingly authentic characters I’ve ever read.

The book is sharp and taught, while everything that happens is driven by a convincing rationale. These characters don’t have many choices to make, if any at all. The plot is simple and tense; there is no need for coincidences or twists. The observations Beverly draws are insightful and relevant, the visuals he paints in your mind are startlingly real.

Dodgers has drawn merited comparisons to HBO gem The Wire and picked up Golden Dagger Awards for both best crime novel and best debut. For me, nothing has matched it for many years. We had some great releases in the noughties and Dodgers is, so far, the best book of the 2010s (is that what they’re calling this decade?).

Check it out. If you already have, read it again.

[Top]Embarrassing climbdown by Waterstones

This doesn’t happen very often: there has been a small victory for independent bookshops over one of the big boys this week…

National bookselling chain Waterstones was forced to backtrack on its intention to open one of its unbranded stores in the same Edinburgh suburb that is already home to an independent bookshop.

The retail giant caused controversy last year when it announced it was opening three outlets in Southwold, Harpenden and Rye without the company’s traditional branding and with different names. The move led to accusations that the stores would surreptitiously appear to shoppers as independent bookshops (surely not?), with just a handwritten notice in the window declaring the true identity of the owners.

Waterstones chief executive, James Daunt, said at the time: “They are very small shops in towns that had independents and very much wish they still had independents but don’t.”

But plans emerged earlier this week that Waterstones was going to open a further unbranded store in the Edinburgh district of Stockbridge where – lo and behold – an independent, Golden Hare Books, is indeed trading, and has been for four years.

The shop’s not-best-pleased manager Julie Danskin told The Guardian: “This will be masquerading as an independent bookshop.”

“James Daunt talks a lot about an even playing field and working with independent brands, but this is essentially backtracking on his previous statements,” she added.

“We don’t have plans to go anywhere and really hope that people will choose to support us, but if more chains open up then we are going to see a homogenisation of streets.”

Daunt was quoted in the Bookseller as saying: “We will be calling it Stockbridge Books and look forward greatly to its opening.”

However, after a swift public backlash following the announcement, Waterstones was forced to change its tune and declared the new Stockbridge store would now display the Waterstones name and familiar branding. Daunt said: “We messed up.”

Yes, you did James – now how about reversing your original sleazy plan and uncovering all your unbranded shops?

There was always something sinister about the tactic of a chain opening unbranded stores under different names; deliberately posing as something you’re not in order to make more cash is simply not on. These shops are just trying to fool people into thinking that they’re bringing much-needed vibrancy to the high street, when in fact all they’re doing is homogenising it.

Do the right thing, Waterstones – claim what you own and work with it.

[Top]5 screenplays that every budding writer should read

When you’re honing your story writing craft, for a book or a script, there’s nothing quite like reading a quality screenplay to get the juices flowing.

The taut, compact nature of a finely tuned screenplay carries an effortless flow, sparkles with clarity and motion. The truly great screenplays, those born from an ambitious yet clearly defined vision and written with a visceral focus and relentless courage, are priceless gifts of inspiration.

So if you’re developing a concept for a story, or have hit a logjam in the writing process, run your eye over these top five movie screenplays that are readily available online. They sure have worked for me…

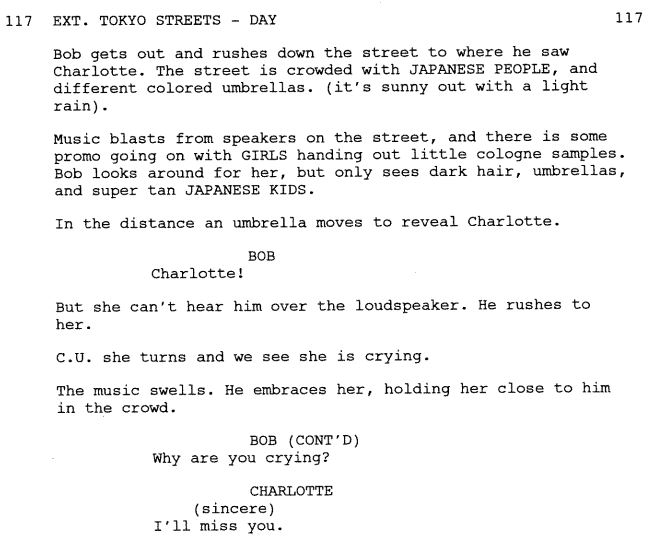

1. Lost in Translation, by Sofia Coppola

This is a prime example of how a series of soft and seemingly inconsequential scenes can drive a narrative along while maintaining interest and intrigue throughout. Coppola’s masterful use of understated dialogue and her development of two main characters at a poignant and relatable crossroads in their lives makes for a charming and moving story set in colourful Tokyo. Of course it helps when Bill Murray and Scarlet Johansson absolutely nail the leading roles.

2. Good Will Hunting, by Matt Damon and Ben Affleck

This duo’s big Hollywood break came in the form of this spellbinding script that served to launch their acting careers. Sharp dialogue and lively snippets of untamed youth give the story early momentum, before the drama really bounces off the page when the relationship between Will and his therapist – wondrously portrayed by Robin Williams in the movie – is fully explored.

3. The Usual Suspects, by Christopher McQuarrie

One of the more plot-driven screenplays in this shortlist, McQuarrie worked with director Bryan Singer on thrashing out a story about five criminals meeting in a police line-up and came up with this scintillating script. Every page is bursting with high-octane action or deep tension, while the canny twist ending is pulled off in exquisite fashion, turning Keyser Soze into one of the most iconic legends of 20th Century cinema.

4. The Big Lebowski, by Ethan & Joel Coen

‘This was a valued rug?’

‘Yeah man, it really tied the room together.’

There’s writing and then there’s the writing of the Coen brothers. Unique, hilarious and always utterly compelling, they construct characters like no other writer. At the heart of their films is the quirky dialogue of their leading protagonists, perhaps no better crafted than here with The Dude. Even if you’re not writing a comedy, the slick and effortless prose of this screenplay is a must-read.

5. Reservoir Dogs, by Quentin Tarantino (background radio dialogue by Roger Avary)

Another script famed for its peerless dialogue, it’s easy to forget how groundbreaking Tarantino’s debut film was considering his seminal future output and how many writers have tried and failed to imitate his style. So much more than a jewellery heist gone south, the searing pace and fluent exposition of this story results in a standout screenplay that any writer should draw inspiration from.

My favourite reads of the year

There has been plenty of captivating fiction that I’ve enjoyed this year, in the crime genre and beyond. Some of my favourites were new releases and others a little older, but here’s a rundown of what gripped me the most, in no particular order…

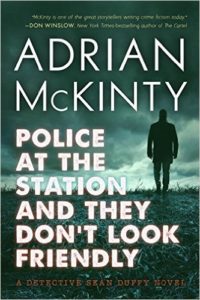

Police at the Station and They Don’t Look Friendly, by Adrian McKinty

The latest Detective Sean Duffy thriller, this is a real page-turner and one of the best in this deeply atmospheric series set in Belfast during the height of The Troubles. The best thing about the Duffy books is that McKinty’s not afraid to age his main characters and evolve their lives, and there was a very different dynamic to this sixth instalment with Duffy’s baby daughter, Emma, along for the ride.

Black Widow, by Chris Brookmyre

It’s been a while since I’ve read any Chris Brookmyre and this novel sees the return of his famed protagonist, discredited hack Jack Parlabane. This time he’s being asked to investigate the suspected death of a recently married IT guru by the victim’s sister, as domestic noir meets intriguing mystery. There are many twists, some more convincing than others, as the plot unravels but Parlabane’s tenacity and human intelligence gives the story real drive.

Anything is Possible, by Elizabeth Strout

This is a wonderful collection of intertwining stories set in the same Illinois rural town as Strout’s previous novel, My Name is Lucy Barton. Revisiting some of those characters, including the narrator, we’re treated to a fuller understanding of incidents given a passing mention in the previous book and a wider scope of these people’s dramatic, disturbing and sometimes surprising lives. Each story comes across as genuine and poignant, with elegant touches of light humour and dark sorrow timed to perfection.

In Sunlight or in Shadow, edited by Lawrence Block

Now this is something truly original – an anthology of short stories, each inspired by a particular painting of the great Edward Hopper. Contributors include Stephen King, Joyce Carol Oates, Michael Connelly, Megan Abbott, Jeffery Deaver, Lee Child, and Block himself. Each story comes illustrated with a colour reproduction of the painting that instigated it, with authors given freedom to interpret Hopper’s ambiguous and stirring narratives as they see fit – and the results are awesome.

Since We Fell by Dennis Lehane

Lehane, a doyen of urban crime/mob writing, turns his hand to more of a psychological and domestic thriller this time, following the downward spiral – and spirited recovery – of a former TV newswoman, Rachel Childs, who marries someone she goes on to fundamentally distrust. It’s something of a departure from Lehane’s back catalogue but it works, the main character’s complex history adding a rich layer of context and drama to a powerful tale.

Eureka Dunes, by Philip Davison

I’ve been a fan of Philip Davison since his Harry Fielding quartet in the early noughties, and this novel is a moving tale of Magnus Sparling, a high-powered Whitehall civil servant who’s called home to Dublin after his father, Edwin, is accused of attempting to poison his wife. The narrative flits between the present day and Magnus’ childhood, including an eloquent depiction of a road trip taken by Edwin and a 14-year-old Magnus through the deserts of California, as the bonds of family life are delicately exposed and tested.

Race to the bottom, by Chris Rhatigan

Rhatigan has a real gift for portraying troubled characters whose choices go on to make their lives spectacularly worse. In this sharp and humorous read, Roy – a borderline alcoholic trapped in a menial job – is dragged into the middle of a murder investigation after a night out with his drug-dealing friend Banksy goes awry. Rhatigan’s visceral prose and rapid plotting makes for one hell of an entertaining read.

All the Old Knives, by Olen Steinhauer

I’d been meaning to get around to this one since its release in 2015, and I’m glad I finally did as it’s another triumph from a talented spy novelist who does a magnificent job of bringing out the human details of espionage. CIA case officer Henry Pelham pays a visit to former colleague and lover, Celia Harrison, who’s since quit to lead a quiet family life in California, in an effort to discover more about a terrorist-hostage crisis in Vienna that ended disastrously six years ago. The tension as they relive the past over dinner in a fancy restaurant is exquisite, and the twist ending sublime.

Green Hell, by Ken Bruen

The 11th in the Jack Taylor series, Bruen’s bitter, alcohol-fuelled PI is back for more, this time taking on a respected but violent professor of literature at the University of Galway. He gets a little help from Emerald, an edgy young goth woman who makes an extravagant appearance. No one writes with such wickedly poetic prose as Bruen, a unique master of the crime fiction trade.

The Highway Kind, edited by Patrick Millikin

We finish off with a thrilling batch of short stories based around cars, driving and the open road – a vibrant, and not to mention uncomfortable, study of American life through its national obsession of the automobile. Contributors such as C.J. Box, George Pelecanos, Diana Gabaldon, James Sallis, Sara Gran, Willy Vlautin and Joe Lansdale give us tales of a car salesman facing the wrath of a psychotic customer, desperate con men, lost youths, wild Apache youth, astonishing road rage and a Mexican drug lord who drives a modified VW bus.

Ebooks v paper books

As a hardened disciple of traditional books – and not to mention a stubborn adversary to change – I was late in joining the rush to purchase an e-reader.

As a hardened disciple of traditional books – and not to mention a stubborn adversary to change – I was late in joining the rush to purchase an e-reader.

But a couple of years now after shelling out on a Kindle Paperwhite, I’ve learnt to appreciate the benefits and accept the drawbacks of digital reading.

With surveys highlighting a recent decline in ebook sales in the UK, the impact of digital reading is becoming a lot more interesting now we’re past the initial ‘new wave’ phenomenon. So now seems an appropriate time to reflect on my pros and cons of ebook and paper reading…

Ebooks – the pros

Storage: I no longer have to sweat about the prospect of squeezing yet another bookcase into the spare bedroom.

Portability: The days of allowing enough space – and weight, if flying abroad – in the suitcase for books when packing for a holiday are over.

More flexible reading experience: When lying in bed or reclining on a sun lounger, an ebook is without doubt easier to hold than a paper book that is typically twice as wide and usually requires two hands.

Cost: They’re cheaper than traditional books (although in many cases not as cheap as they used to be).

Ebooks – the cons

Imagery: They’re black and white, diluting the important pleasure of fully admiring the front cover or any images inside.

Checking back: I just need to go back a couple of chapters – or was it a few more? – to remember an incident or minor character that’s returned to the action. I use the scroller at the bottom of the page to guess where it is I need to jump back to, but it takes time – I’m hopping around only able to see one page at a time. Flicking back through physical pages seems to give me a quicker and firmer steer of a narrative’s history.

Sifting through the archives: I often delve into books I may have read months or years before just to recall a particular passage. It’s much nicer (and easier, I find) to browse the spines on the bookshelves, pluck out the book I need and skim through the pages rather than scroll through my electronic library of previous books in order of purchase. Searching through previously read books on an e-reader just feels like a more laborious, soulless process.

Progress just isn’t a percentage thing: Mmm, I’m 63% of the way through a book. Although I appreciate the mathematical accuracy, I much prefer to gauge how far I am through a story by judging the weight of the tome in my hands, or closing it with a bookmark in place and checking out the top-of-the-page edges.

Paper books – the pros

Physicality: Any paper book is an actual thing that was printed, bought and sold (perhaps many times over), and is in your possession for however long you wish. Each and every book is an artefact, with its own look, feel and smell; each mark, blotch, fade or fold making it unique. It’s also available for you to consume whenever you like, just by flipping the cover. There are no batteries to run down or technical hitches. Once my e-reader froze and wouldn’t re-start properly for a couple of days.

Screen break: Like many of us, I spend all of my working day in front of an electronic screen. Yes e-readers come with a smart light setting that can be dimmed in dark rooms to help your eyes, but there’s nothing quite like reading for pleasure while giving yourself a screen break.

Sharing: You can swap and share favourite or recommended reads when meeting up with friends and family, adding a social element to your reading experience.

Casual ownership: If you’re on the beach and fancy a dip in the sea, you feel pretty easy about leaving a paper book by your lounger while you wander out of sight. It’s difficult to take that casual approach with a £100+ device that holds much of your library.

Paper books – the cons

You need light: At night, you have to turn on a light or bedside lamp and risk disturbing your partner.

No choice on presentation: Some books just seem to come with an ugly font or a too small/large type size – and you can’t do anything about it. With ebooks, you can adjust all of that to suit your liking.

The waiting game: Unless you’re in a bookshop (and there’s obviously not many of those left), you can’t just decide to buy a book and then have it seconds later, unlike when ordering an ebook with literally just one click. When ordering a paper book online, more often than not you’re waiting a few days, or sometimes weeks, and at the mercy of the mail delivery companies.

Bad for the environment: There’s no getting away from the fact that, even in these times of sophisticated recycling schemes, the production of paper and ink for printing has a harmful effect on the environment. How this compares to the greenhouse gas emissions of e-readers, however, is up for debate.

Which side are you on? Drop me a line at @PaulJGadsby to discuss the ebook v hard copies debate.

[Top]280 Steps – the sad demise of a cherished indie

While it’s never a resounding shock to hear of an independent publishing company shutting down, it was nevertheless a pretty hefty kick in the teeth to hear about the recent closure of 280 Steps.

While it’s never a resounding shock to hear of an independent publishing company shutting down, it was nevertheless a pretty hefty kick in the teeth to hear about the recent closure of 280 Steps.

This savvy and ambitious indie launched in 2014, specialising in a range of crime fiction from hardboiled noir to mysteries and thrillers. As well as publishing established writers and re-issuing out-of-print pulp classics from around the globe, it made a sterling effort to scour the shadows for the rising stars, the fresh new voices that would inspire the next generation.

And boy did those new voices come; Eric Beetner, Andrew Nette, Jake Hinkson, Josh K Stevens, Rob Kitchin and Eryk Pruitt among them, lighting up the contemporary crime fiction scene with their crisp, gritty stories that gorged readers’ appetites for original themes that defined the times.

Not only was the writing taut and absorbing, the books came wrapped in dishy, retro cover art that 280 Steps made its mantra. They didn’t just stick to novels either, never afraid to take a punt on short story collections and novellas, in traditional and e-book formats.

The 280 name was a reference taken from Raymond Chandler’s 1940 novel Farewell, My Lovely, the second outing of iconic LA private eye Philip Marlowe. “It was a nice walk if you liked grunting. There were two hundred and eighty steps up to Cabrillo Street.”

Will we see their like again? Well there’s a few small indie publishers that carry the same ideals still about or have recently come aboard (All Due Respect, Down and Out Books, Fahrenheit Press – the latter’s savoir-faire use of social media is a particular standout delight), and hopefully more still will emerge, but there’s no doubt that the fall of 280 Steps leaves a gaping hole.

It comes off the back of another crime indie loss, Blasted Heath, the digital publisher in Scotland that shut up shop in March after a proud six-year run. The publishing industry is always changing; patterns are forever emerging and disappearing – it’s just a shame to see so many important creative businesses and talented writers fall victim to economic woes.

In today’s cut-throat world of big-boy spending power, retail domination by the (very) few and, it has to be said, people’s buying habits, especially here in the UK where many people’s idea of doing their bit for the publishing trade is splashing out on a celebrity autobiog or cook book for a relative’s Christmas present, there’s not much room for bold publishers to open their doors to unsolicited submissions, follow their gut, put their faith in unheralded names and release outstanding material.

At least everyone behind the 280 Steps venture can claim they did that.

[Top]10 of the best book sequels

Writing a follow-up to a big hit can be a huge challenge and one that few authors really pull off.

Writing a follow-up to a big hit can be a huge challenge and one that few authors really pull off.

But here are 10 fine examples where the sequel does full justice – or even enhances – a fantastic crime novel that caught the imagination. Huge success stories in their own right, you could say…

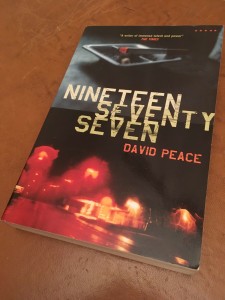

Nineteen Seventy-Seven

David Peace’s evocative debut novel, Nineteen Seventy-Four, made a big impact on the British literary crime scene and his follow-up, Nineteen Seventy-Seven, gave us more of his vivid depictions of a corrupt Yorkshire police force and bleak, northern communities terrified and bewildered by the Yorkshire Ripper murders. This sequel was a standout slice of what turned out to be a four-part series labelled The Red Riding Quartet, featuring several recurring and connecting characters, the flaws and fights of all them beautifully described in relentless, unyielding fashion.

The Big Nowhere

If The Black Dahlia turned James Ellroy into one of the hottest crime writers around in 1987, his sequel to it a year later, The Big Nowhere, elevated his status to one of the most powerful literary voices in crime fiction history. An engrossing tale of disgraced detectives, alcoholic anti-heroes, Hollywood Communists and a brutal sex murderer set against the backdrop of a post-war Los Angeles smeared with greed, deception and paranoia, this is a disturbing masterpiece.

Driven

I describe James Sallis’ scintillating short novel Drive elsewhere on this site as ‘a work dripping with existential minimalism, taut plotting, brutal hostility and sharp-witted dialogue’ and the book’s main character, the ‘Driver’, a Hollywood stunt driver by day and a wily getaway wheelman for the LA criminal underworld by night, returns in Driven. This is a classic sequel that, set seven years later, digs deeper into the instinctive make-up of this cryptic hero while taking the reader on a glorious ride. Modern noir at its finest.

The Dead Yard

Adrian McKinty’s stunning novel Dead I Well May Be introduced us to Belfast-born Michael Forsythe, an ambitious and resourceful lackey for a New York mob who, after being double-crossed big time, grows up fast into a cool and cunning killer. Five years later in The Dead Yard Forsythe is infiltrating an IRA sleeper cell in New England, living by his wits, falling in love and killing time and time again in order to stay alive. Few thrillers, if any, are written with such convincing action sequences as this rip-roaring read.

Ripley Under Ground

Patricia Highsmith’s wonderful follow-up to The Talented Mr Ripley is a fantastic psychological thriller and also a fine example of re-visiting a defining character in a very different setting to how they were introduced. The days of posing as Dickie Greenleaf behind him, Ripley is now living with a stylish – and of course wealthy – wife in rural France and running an art forgery scam, but after being exposed faces an enthralling battle to maintain his lavish Continental lifestyle and his freedom.

Farewell, My Lovely

Raymond Chandler brings back LA private eye Philip Marlowe in this 1940 sequel to The Big Sleep. This glorious book oozes style with an array of dazzling dialogue as Marlowe gets dragged into a murder that leads to a gang of jewel thieves, city corruption and a whole lot more murders. No wonder it was adapted for the screen three times.

Live and Let Die

This second James Bond book is a classic that builds on the momentum of Ian Fleming’s debut hit, Casino Royale. A lightning quick plot taking in striking locations such as Harlem, Florida and Jamaica together with some sharp characterisation allows readers to get deeper under the skin of this fascinating secret agent. The tone of this book, released in 1954, is heavier than the first as Fleming does a terrific job of placing Bond at the heart of these formative Cold War years, as well as in the middle of tense Anglo-American relations.

McKenzie’s Friend

Irish writer Philip Davison introduced reclusive MI5 understrapper Harry Fielding in The Crooked Man in 1998, and three years later brought him back in McKenzie’s Friend, a delightful novel exploring Harry’s complex relationship with his arrogant employers, his dementia-stricken father and his old mate Alfie, a bent cop who’s about to drag Harry deep into the mire.

Live by Night

Dennis Lehane’s epic follow-on to The Given Day, this is heavyweight crime fiction at its hard-hitting best. Joe Coughlin turns from small-time thief to big-time outlaw in 1920s Boston in this sprawling journey of violence, betrayal, love and pain. One of those rare examples of a long book that’s quick to read.

Donkey Punch

Cal Innes, our damaged hero from Saturday’s Child, has left his PI business behind to take on a caretaker’s job at a Manchester boxing club in this cross-Atlantic classic by Ray Banks. Shepherding/babysitting promising amateur pugilist Liam to a tournament in Los Angeles, Innes gets more than he bargained for when he discovers the competition is fixed by the kind of sinister underworld types he thought he’d left behind in the gritty north.

Honourable mentions must also go to the following sequels – some outside of my treasured crime fiction genre – that nearly broke into the top 10 (and funnily enough make a top 20):

Closing Time, Joseph Heller’s follow-up to Catch 22

The Crossing, Cormac McCarthy’s sequel to All the Pretty Horses

Imperial Bedrooms, the follow-up to American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

The Killing of the Tinkers, Ken Bruen’s sequel to The Guards

The Growing Pains of Adrian Mole, Sue Townsend’s follow-up to the best-selling The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole

The Sicilian, regarded as Mario Puzo’s literary sequel to The Godfather

Porno, Irvine Welsh brings Renton and Co back 10 years after Trainspotting

Go Set a Watchman, Harper Lee’s sequel – or earlier draft, depending on your take – of To Kill a Mockingbird

The Lost World, Michael Crichton’s follow-up to Jurassic Park

Bring up the Bodies, Hilary Mantel’s sequel to Wolf Hall.

Why Ken Bruen is a true original

Ken Bruen turns 65 today, but if you read his work you’d never be able to tell as his writing is laced with a gloriously fresh, youthful verve.

Ken Bruen turns 65 today, but if you read his work you’d never be able to tell as his writing is laced with a gloriously fresh, youthful verve.

I see the Irish crime novelist as one of the finest modern noir writers around, and although he’s won some prestigious international awards (two Shamus gongs, a Macavity and a Barry Award) he deserves to be acclaimed on a much wider scale, way beyond the kudos of the crime fiction elite. If anyone’s writing should be breaking through into the mainstream to be enjoyed by a lot more people all over the globe, it’s his.

Born in Galway in 1951, Bruen was an early reader but it was a while before he got published. After completing a PhD in metaphysics he spent 25 years teaching English in Africa, South East Asia and South America, his time in the latter marred by an incident that has haunted him – and his creative output – ever since. In Brazil he was wrongly imprisoned, tortured and raped. When a traumatised Bruen was released, he weighed six stones.

Put on a plane to London, he set up roots in Brixton and blended his rich, stark experiences with a long-nurtured edgy writing style and black humour to create his debut novel, Funeral. Bruen harnessed his craft and in 2001 released The Guards, the first Jack Taylor novel, his most well-known series.

An alcoholic ex-Guard (fired from Ireland’s police force in disgrace of course), Taylor is a private detective by default and, through a mixture of tenacity, luck, intuitive investigative skills and a heartfelt loyalty to his clients, often rundown and desperate themselves, he becomes dangerously good at it. Bruen really gets Taylor, the authentic first-person prose making Taylor’s drunk-philosopher-slash-vengeful-anti-hero persona appear preposterously real. In fact, a more genuine, flawed character you’re unlikely to find.

Bruen eventually moved back to Galway, where the Taylor books are set, and has since created the Brant series, based on a psychotic London-based cop and penned several exceptional standalone works, the highlights being American Skin, Tower and London Boulevard, the latter adapted into a film starring Colin Farrell and Keira Knightly.

Bruen’s narratives are dripping with hard-boiled intent from the off. Some of his intros go way beyond hooking the reader in, they damn near weld your eyes to the page. Here are just a few examples that carry terrific bite as well as disturbing intrigue:

“Am I dying?”

Answer that. Do you lie big and say, like in the movies, “Naw, it’s just a scratch”? Or clutch his hand real tight and say, “I ain’t letting you go, bro’,”? (The McDead)

The blast took her face off. (Her Last Call to Louis MacNeice)

Griffin coughed blood into my face when I made to slip the chains under his shoulders. (Tower)

It took them a time to crucify the kid. (Cross).

The intensity rarely dips, his chapters short, his sentences rapid and his prose muscular, his output always wonderfully original. Bruen’s habit of defining his protagonists by their cultural tastes – often declared through listing their favourite music, films, books, clothes or cuisine – has also won him many fans.

The glowing reviews will keep coming, but it’s high time this champion of the crime genre was hailed as a great of modern fiction worldwide.

[Top]My top 10 books of the year

It’s been another year of cracking reads and scintillating crime fiction, so I thought I’d share my favourite books – some new, some not so new – that I’ve read during 2015. In no particular order and all that…

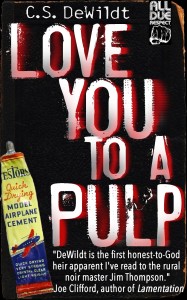

Love you to a Pulp, by C.S. DeWildt

Love you to a Pulp, by C.S. DeWildt

This for me was one of the hits of the year – a bold, quick-fire slice of American rural noir that never stops for breath. Neil Chambers, a glue-sniffing, hard-hitting private detective scythes and stumbles his way through the Kentucky countryside trying to solve the murder of Hoon, the boyfriend of a client’s daughter. Competing with an assortment of scammers and thugs – not least his former colleagues at the local police station – to get to the truth, Chambers drags himself through the depths of despair on a colossal journey. Interspersed with some graphic flashbacks to Chambers’ cruel and violent upbringing, Love you to a Pulp is a haunting and chaotic classic that has drawn fair comparisons with noir master Jim Thompson.

Hidden, by Emma Kavanagh

A stirring psychological thriller, this book is a triumph thanks to the author’s choice of format in unravelling a compelling story. A gunman goes on a shooting spree in a hospital canteen. We then rewind a week and experience the build-up to this tragedy not just inside the head of the killer but also from a journalist, a psychologist and a firearms officer. Multi-viewpoint fiction doesn’t always maximise the drama of a narrative, but in this case Kavanagh pulls it off in style.

The Axeman’s Jazz, by Ray Celestin

Based on the true story of a serial killer who terrorised New Orleans in 1919, this atmospheric novel is a fine example of a specific time and place being explored in such intricate detail that the setting becomes a vivid and absorbing character itself. This charismatic city is harnessing the art of jazz music against the backdrop of WW1-returning soldiers, frayed race relations on the vibrant streets and the rise of the mafia. We follow three very different detectives all vying to unmask a violent killer who strikes at random, gleefully slicing apart innocent families. Who’s going to crack the case becomes more interesting than who the murderer is in this ambitious, evocative debut. And there’s even a place for a young Louis Armstrong.

Matador, by Ray Banks

Ex-bullfighter Raf survives life-threatening injuries to come back and take on an ageing British gang of mobsters who thought they’d finished him off in the Costa del Sol. I love Ray Banks; he writes gritty crime with such authority and strikes at the heart of what’s really personal about each of his characters, making their actions always seem truly believable because they’re utterly in line with their gut fears and aspirations. He nails the Spanish setting (a far cry from his traditional northern England locations), the Tarantino-esque quest for revenge and the cat-and-mouse thrills, while the massacre at the end is just glorious.

The Deepening Shade, by Jake Hinkson

A wonderful collection of thought-provoking short stories, Hinkson explores not just the dark side of humanity here but also the resilient one. His range of damaged, hardy and farcical characters include a heartbroken alcoholic cop trying to prevent Dick Cheney-masked gunman robbing a petrol station, a lesbian couple running a homeless shelter aiming to save a tragic young woman controlled by a self-proclaimed prophet, and a stripper prepared to kill a man in order to protect her sister from going to jail. Hinkson isn’t afraid to tap into heavyweight themes, religious fundamentalism being a recurring one, but he skilfully manages to give his stories a moral punch without laying the righteousness on thick.

The Drop, by Dennis Lehane

Regular readers of this site will know I’m a big fan of Lehane, and here he returns to his native streets of Boston to give us the taut tale of unassuming barman Bob Saginowski, who finds himself at the heart of a robbery gone awry at the Chechen mob-run bar where he works. The Drop is also a touching love story, and no one does unspoken emotion better than Lehane, who adapted this book from a screenplay he wrote for the film of the same name, which became famous for being James Gandolfini’s final movie.

Munich Airport, by Greg Baxter

I adored Baxter’s previous novel, The Apartment, and was delighted to see the same reflective, lyrical prose produced in this book, the story of the impact a young woman’s suicide through anorexia has on her brother (the unnamed narrator) and father. The two, now off food themselves, are stranded at Munich Airport waiting for bad weather to clear in order to fly her body home to the States. The young woman, Miriam, had been living estranged from them in Germany and the story backtracks over the last few days as the two of them search for reasons why Miriam’s life deteriorated as well as their own memories of her childhood. Gloomy, intense, but most of all rich in character, this is a beautiful work.

Two Bullets Solve Everything, by Ryan Sayles and Chris Rhatigan

A nice little collection of two briskly-paced novellas here; one good, the other outstanding. In Disco Rumble Fish, Ryan Sayles guides us through a SWAT team’s dramatic operation to home in on a criminal who aided a mobster’s violent jailbreak, in which an officer was killed. In Chris Rhatigan’s A Pack of Lies, corrupt local newspaper reporter Lionel Kasper gets in way too deep after being forced into a badly-hashed murder in order to protect his crooked methods. Kasper is a resourceful but sly loser of the highest order, and the powerful voice that Rhatigan gives him works a treat.

The Rainbird Pattern, by Victor Canning

Winner of the Crime Writers’ Association Silver Dagger in 1972, I read this charming and intriguing caper for the first time this year and loved it. Wealthy old spinster Miss Rainbird offers her spiritual medium Blanche Tyler a wad of cash to locate her long-lost illegitimate nephew, Edward Shoebridge. Blanche and her boyfriend George Lumley take the job on, only to find Shoebridge is making a ton of money for himself by kidnapping high-profile people across southern England and collecting tidy ransoms for their safe return, and he’s in no mood to be discovered by two chancers. The story was later adapted for the screen as Alfred Hitchcock’s final film, Family Plot.

11:22:63, by Stephen King

Time travel isn’t really something that has gripped me before within the realms of literature, but this book is a striking exception. King is a genius, of course, but in this tale his writing scaled heights I’ve never witnessed from him before as he lifts this story vividly to life. As ever, it’s all in the tiny details, and his creation of a time portal in the pantry of a diner that sends people back to 1958 is a wonderfully persuasive piece of imagination. Bored school teacher Jake Epping sets himself the task of travelling back in time to prevent Lee Harvey Oswald from assassinating JFK in Dallas in ’63, which is a heck of a plot to draw anyone in. The only downside is, like much of King’s work, it’s too long and he could have cut 200 pages out of this dense tome and not lost a jot of drama.

Elmore Leonard – the undisputed king of dialogue

This week marks the 90th anniversary of the birth of Elmore Leonard – a phenomenal writer who surpassed them all when it came to mastering dialogue.

This week marks the 90th anniversary of the birth of Elmore Leonard – a phenomenal writer who surpassed them all when it came to mastering dialogue.

One of the most important aspects of fiction writing, dialogue is an area that often sorts the wheat from the chaff in authors.

Many can excel in areas of plotting, character development or harnessing elegant prose, but all too often it’s the dialogue that trips them up, that takes that crucial edge away from their otherwise carefully drawn characters.

But not for Leonard. Never. The guy always seemed to know exactly where to drop what words in to each line of dialogue for maximum effect. He played with speech in technical ways that no one else could, using comma splices, stark tension shifts, mangles of half-truths and cross-purposes that enriched his characters and brought their voices – together with their fears and dreams – to life.

For many writers, their dialogue ends up – at best – backing up their character creations, enforcing what they predominantly express through their prose. But Leonard used speech in itself as a sheer driving force to hook readers in, to move a story forward, to build suspense, to spring a surprise or to fashion a knockout ending.

He started out publishing westerns in the 1950s, not because he desperately wanted to write them but because he saw it as an under-crowded genre where he could carve out a reputation for himself and build a platform for his career. Thankfully his confidence – and growing talent – led him to concentrate on the natural flows and spurs of his writing rather than any commercial considerations and he turned his hand to crime writing.

1974’s 52 Pick Up was an early classic along with Unknown Man No. 89 (1977) and City Primeval, published in 1980. Leonard’s major breakthrough came five years later with the sublime Glitz, and he went through a period in the late 80s/early 90s when he was simply untouchable. Adored by his readers and revered by his peers, he sold millions of his books while earning constant respect from the literary elite, his standout hits being Freaky Deaky (1988), Get Shorty (1990) and 1992’s Rum Punch, later adapted into the Tarantino gem Jackie Brown.

Many of those crime novels were set in Detroit, where he spent the prime years of his life, and he later earned the nickname ‘The Dickens of Detroit’ for his accurate and intimate portrayals of people from that vibrant city.

One of the most popular and prolific writers of all time, Leonard had chalked up 45 novels along with dozens of screenplays and short stories before his death in 2013.

He could do gritty, funny, plucky and nasty in roughly equal measure, and he offered a glimpse into his creative insight when publishing his ‘10 Rules of Writing’ which included the delightful nuggets ‘Never use the word suddenly’ and ‘Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip’.

Nice one, Elmore. We miss you.

[Top]